With more than 5.3 million displaced people, Colombia ranks second in terms of internally displaced populations. This is the backdrop to the new film Siembra directed by Santiago Lozano Álvarez and Ángela Osorio Rojas. Siembra tells the story of Turco (Diego Balanta), a displaced fisherman from the Pacific coast begrudgingly living in Cali, one of Colombia’s largest cities, and wishing he could go back to the land he knows best by the sea. Faced with the death of his only son Yosner (Jose Luis Preciado), who enjoys breakdancing and who seems to have found his place in this new environment, Turco must come to terms with his newfound life.

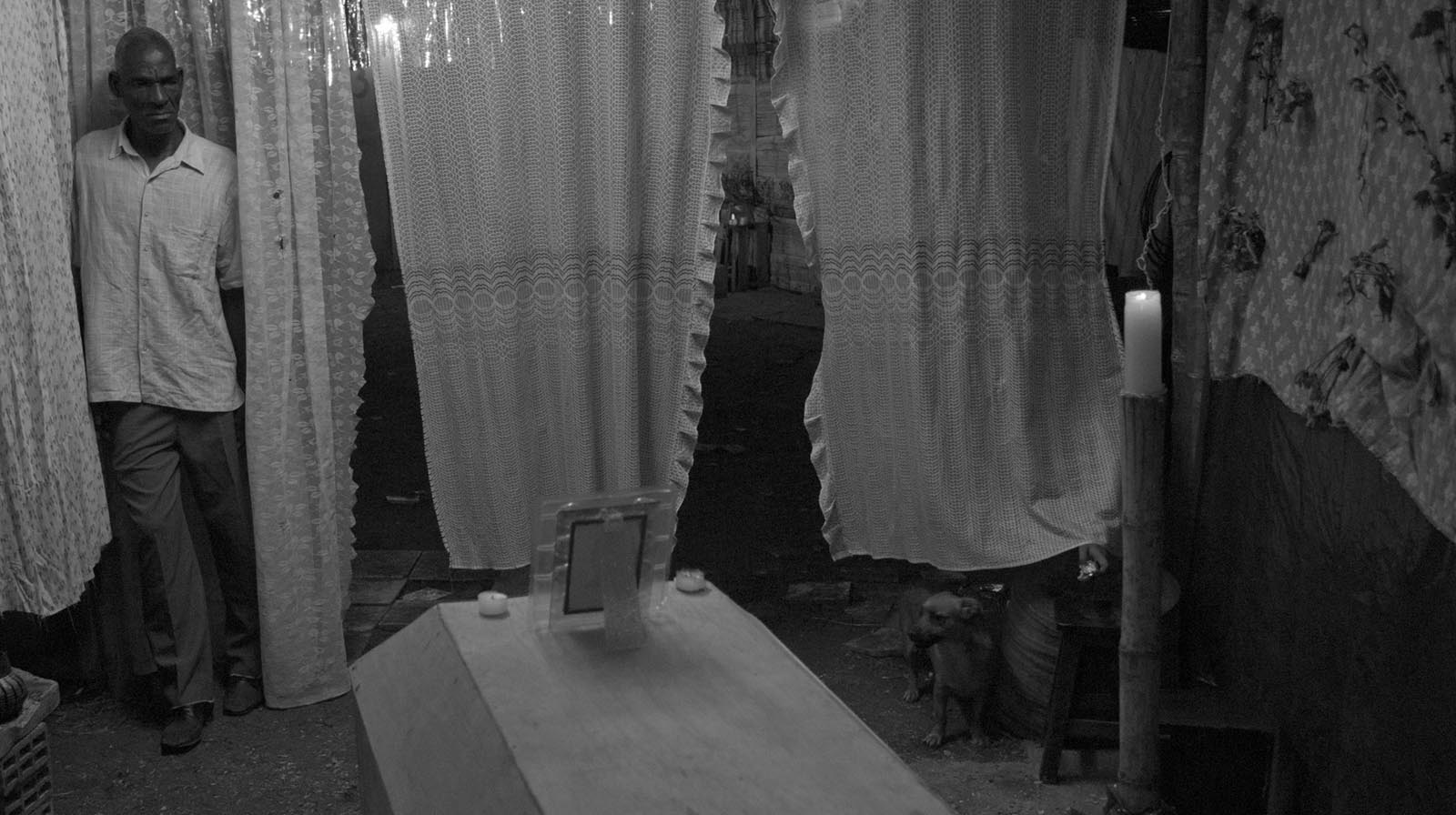

Shot in black and white, Siembra is a somber but hopeful look at the resilience of the Colombian people who have begun to glimpse a possible peaceful future in these past few years. The title then (“to sow”) takes on a more metaphorical sense when Turco is tasked with needing to lay down his own child, to return him to the ground. Trying to scrounge up enough money to afford the casket, battling petty bureaucracy to arrange the funeral, and looking for why his son was taken from him so soon, Turco takes us on a journey through these poverty-stricken communities that refuse to be broken. Dancing with no abandon, creating artwork out of recyclables, these are people who find beauty where they can.

While the subject matter may sound dour and depressing, Siembra is constantly sowing the seeds of hope throughout, finding beauty in melancholy mourning. Part of that has to do with the fact that Lozano and Osorio went out of their way to cast artists rather than actors — those breakdancing moves you see Yosner practicing at the start of the film give you a sense of Preciado’s talent which his directors are all too happy to share with the world.

Hot off winning a Special Jury Prize at the Cartagena Film Festival, we talked to co-director Ángela Osorio Rojas about the film’s warm reception at festivals worldwide, the social message at the heart of the movie, and the beauty of shooting in black and white. Check out some highlights of our chat below.

On The Film’s Social Message

“We wanted to write something about the displaced population, not in terms of the violent drama that causes it, but to see what comes after.”

We started thinking about this idea of land and the way in which Colombia is changing its own territories. Not only in a geographical sense (people losing the land that’s rightfully theirs to violence) but also on a cultural level (with people traveling with their own customs to new cities). So we wanted to write something about the displaced population, but not in terms of the violent drama that causes it, but to see what comes after. So the guiding question was “Y mañana qué?” With that tomorrow being a day from now, two days, three days, four months, a year, three years…

We wanted to think through what happens when there’s no closure. When you’re left in limbo, almost. Siembra’s Turco lives in that space. He feels like he hasn’t yet arrived to where he’s supposed to be, where he’s gonna put down his roots. The film is about him trying to find closure and root himself to where he is now, in this new land.

On Mourning As Battle

There’s two ways of looking at mourning. Immediately, you think of it in terms of death, with very sad tone. But then, if you think of the Spanish word for it (“duelo”), you find that its other connotation is about confrontation — a duel of sorts. So when you’re in mourning (“en duelo”), you’re not just closing a chapter but you’re facing something new. And in that sense, every day is a battle. That’s what you see in those dance battles (also called “duelos,” or duels). So it’s about Turco facing his mourning with yet another loss that changes his outlook about where he was and where he is.

On Shooting In Black And White

“The feeling we want audiences to leave our film with, is not a sense of helplessness but one of resilience.”

We decided to shoot in black and white because in a way it makes the film work at a figurative level. It forces you to focus not on reality itself but on understanding the storytelling we were crafting. That is, to narrow your own point of view and get rid of any idea that what we are presenting you with is the “truth” or something close to it. This isn’t realism. This isn’t a documentary, this isn’t reality, but a film that allows us to reflect what is going on. And the black and white cinematography allowed us to do that quite openly. That’s what cinema allows you to do. Not to reproduce life but to allow you to reflect on it. Once we began to shoot in black and white we realized we had to pay closer attention to textures. That opened up a whole other dimension to the film’s look and it seemed perfectly suited to what we were focusing on. If you look at the houses of these people who come from the countryside and have to restart their lives with whatever they can find, you see them building stuff from what’s around. A type of collage. So it’s a mish-mash of textures all around. And then in terms of centering a story on Afro-Colombian characters, shooting in black and white allows you to think and see skin color very differently. It’s all about shading and textures, not just about black or white, mestizo or trigueño, but about a wide gamut of skin tones, celebrating the mix of them all.

On The Film’s Hopeful Ending

For us, the film is only finished when it’s shown to an audience. Getting an audience in front of a film is a way of making it come alive again. What’s been interesting to see here in Cartagena that hasn’t really been the case anywhere else, is people really talking about that hopeful tone of the final moments of the film. It’s important for us to really think through that. To not get bogged down in a pessimistic attitude that strips you of the tools you need to rebuild. Because if you find yourself in that negative headspace you’re left wondering, why am I even fighting any of this anymore? And you’re left unable to move on. So the feeling we want audiences to leave our film with, is not that sense of helplessness but one of resilience. Like, I too can look ahead.

And then there’s the idea that we wanted to think through the issue of displaced populations as a deeply personal one. We’re so used to talking about it in terms of numbers and statistics (how many have been displaced, how many cities have been affected) that we wanted to give a face to that struggle. For audiences to really make a connection with those faces and those characters and those stories. And that’s definitely been the case with Turco, he’s clearly hitting a nerve with audiences everywhere.

Lastly, we also wanted to shift the narrative and not only see the story of these displaced people as being one that ends at the point where they flee their homes, but to think about what comes after that. To move away from thinking that the worse has already happened. Like I said, to think in terms of “Y mañana qué?” A question we’re all thinking about here in Colombia seeing as how the peace talks inch us ever closer to imagining a future where the violence may soon end but of course, that’s not the end of the story, we’ll still be left with that question. What now?

This interview was conducted in Spanish and has been translated by the author for Remezcla. Siembra screened as part of the 2016 Miami Film Festival.