Latin American rock, once a niche promise of the equatorial countries, is fast reaching maturity. One can’t help but imagine the bleak future that awaits such bands, who are likely sitting on some golden throne, resurfacing only to churn out middle-of-the-road singles and cash in on nostalgia tours, before retiring back to their Porfirian-age haciendas. For all we know, that’s what Maná and Jaguares are doing right now.

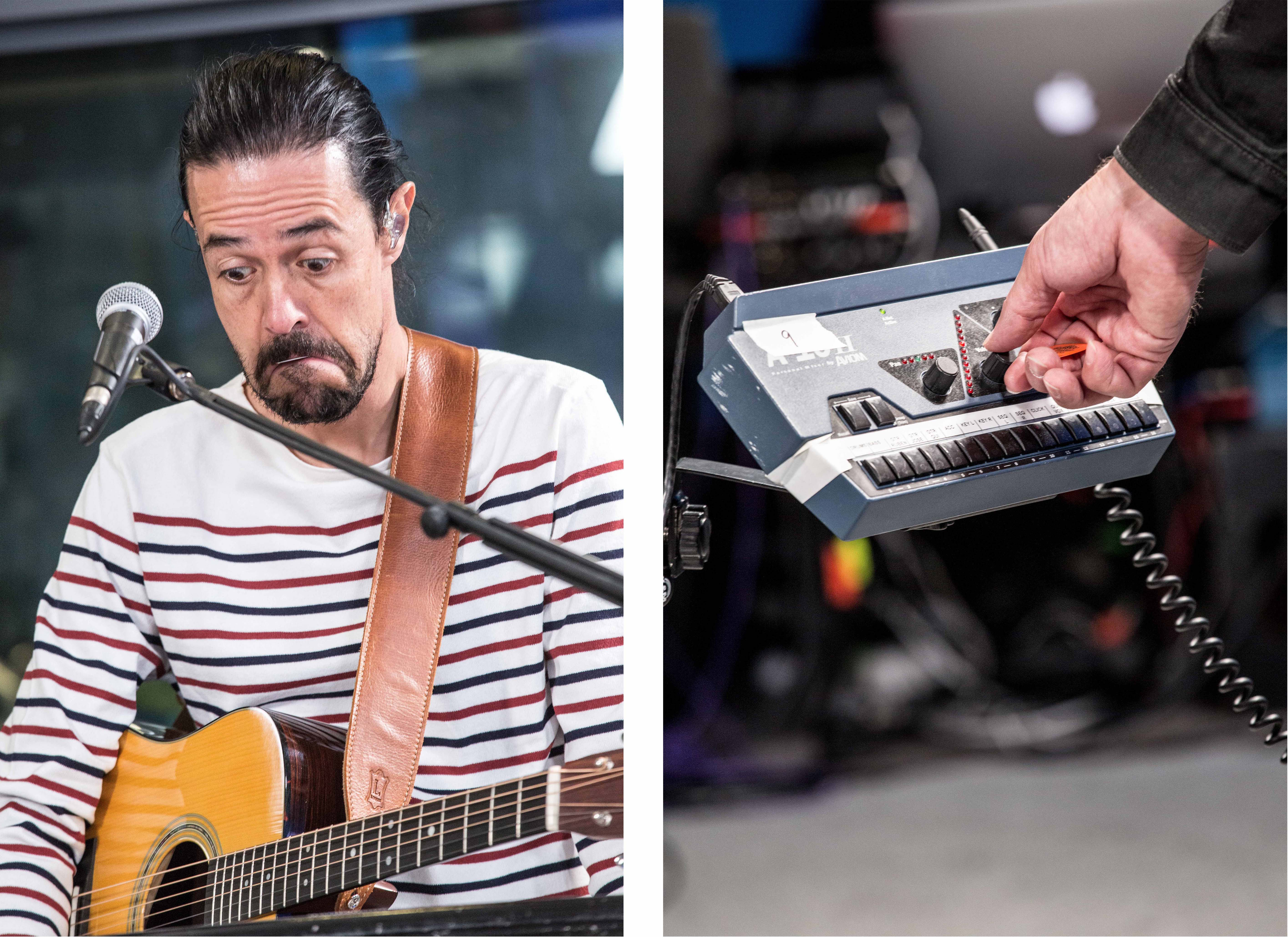

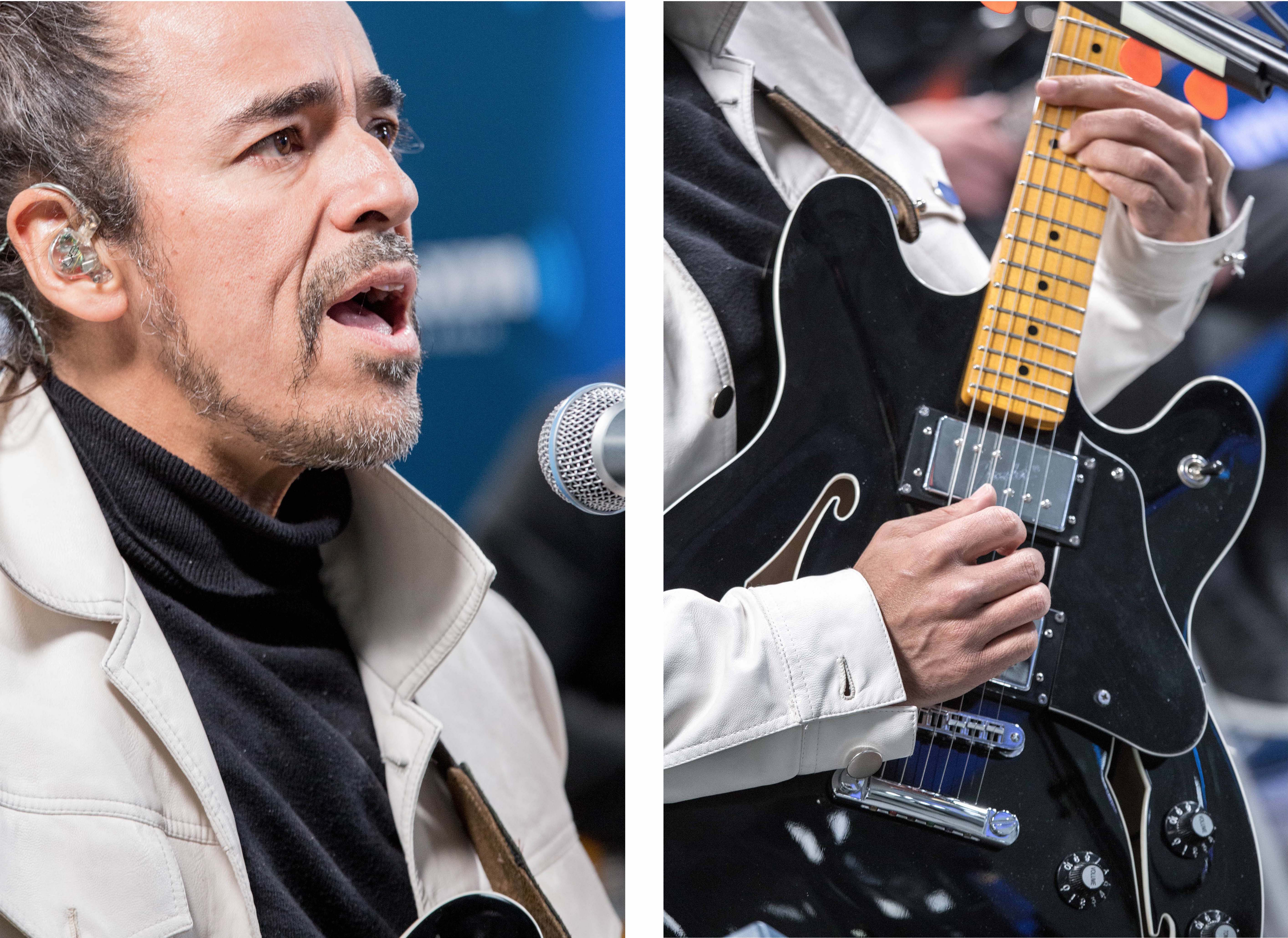

Not Café Tacvba, though. Throughout their 27-year run, they’ve proven, time and again, to be as creatively fertile as they were in those sandal-clad, folk-infused early years, when first they broke out of the Satélite suburbs and redrew the map of Mexican music forever. With Jei Beibi, the band’s first studio album in five years, fans – who have etched the memories of their hormone-fueled youths into their music – are once again forced to reevaluate every assumption they hold about Cafeta.

Take their single “Futuro.” The title can initially seem ironic, given the fact that the band has always been so emblematic of the past, particularly Mexico’s longstanding folkloric tradition. But it’s the perfect metonym for their unrelenting commitment to redefinition, in spite of – or perhaps because of – their enormous legacy. It’s easily one of their most iconic songs – not just in the last few years, but ever.

As infectious as that song is, with its ZZK-style Andean cumbia flourishes, you won’t find another like it on Jei Beibi. Contrary to the almost constrained focus of their last effort El Objeto Antes Llamado Disco, no two songs sound alike on this project. Of course, the band has pretty much built a career on eclecticism. “The diversity in our rhythms and in our sonic palette has always been something that’s defined the band,” says member Quique Rangel in an interview with Remezcla.

“Rock seems to me like a way of facing or confronting things.”

“We don’t think about it in terms of eclecticism,” says Emmanuel Del Real (aka Meme). “Rather, it’s about communicating with each other. All four of us are composers, and everyone has something to say. We each build our ideas individually and then take them to the group. That’s where it becomes eclectic,” he says. The eclecticism is a consequence of having four restless minds working together. “The diversity of our ideas is amplified when they’re multiplied by four,” he explains.

In many ways, Jei Beibi harkens back to another album in the band’s repertoire. “The variety of genres it contains reminds us a bit of Re,” says Rangel. “That’s the album where we opened up the field for experimentation, in terms of rhythms and sounds.” That experimentation came at a cost, as the band soon learned. “There was a part of our audience that had followed us fervently that turned their back on us,” says Rangel. “They questioned that shift, which for us seemed natural.”

Re was the first instance where the band used the studio as an instrument for their experimentation, and this jump proved too shocking for some fans, who were used to band’s early raw sound. It would become a recurring theme throughout their career. With Sino, which was their first foray into more traditional rock territory, the band once again came under scrutiny. “Audiences were skeptical of that too,” notes Rangel.

More so than any other work, it was Re that cemented the band as rock’s decolonial ambassadors, as they used the Western genre and infused it with centuries of folkloric tradition in a way that no other band had done before. Much in the way that Los Prisioneros addressed the contradictions of being a rock band in Latin America through their confrontational and sardonic lyrics (in songs like “We Are Sudamerican Rockers” or “El Baile de los que Sobran”), Café Tacvba did so through their sound. Both bands ultimately veered away from those statements, however resonant they proved, going against what audiences had come to expect of them.

“Prisioneros were this kind of new wave, punk band, but suddenly, their most successful album was an electronica album,” offers Del Real, alluding to the band’s 1990 album Corazones. “It didn’t have the discourse that their earlier protest albums had.”

For Del Real, Los Prisioneros’ drastic shift in sound, which parallels Café Tacvba’s own creative leaps across albums, is an inherent characteristic of rock music. “Rock seems to me like a way of facing or confronting things,” he says. For him, it is less a sound, and more an adventurous approach, shaking listeners out of their comfort zones by going against their preconceived notions, whatever these may be. “[Corazones] is a fantastic record,” he says. “It has that same spirit of rock precisely because it went against what people expected of them.”

But Del Real argues that rock’s current state is lacking in compelling offerings, especially when it comes to using the genre as a vehicle for social commentary. According to Rangel, the biggest political statements in music today aren’t happening in rock, but in hip-hop. “I feel that hip-hop has taken over that attitude; it has taken over that sense of defiance against society and the status quo,” he says. “I don’t think there is something like it in Latin America, with reggaeton for example, which is the closest parallel to hip-hop. Save for Calle 13 and a few other acts, I don’t see that attitude or sense of questioning present in the genre.”

“It’s about the possibility of things getting better, about how it’s worth fighting to make things better.”

A lot of this dissent has also migrated into the realm of social media. “The way I see it, rock, like any genre, comes out of necessity. The artist needs to say something and they do it through rock,” says Del Real. “I think a lot of that is diluted nowadays because a good part of that discourse happens within social media. People who have the need to say or criticize something quickly reach for their phones or their device of choice and they vent in that way.”

It’s hard to argue with the fact that a good deal of political discourse is happening online. Some of the most noteworthy political movements in Mexico of the past few years – like #1DMX and #YoSoy132, both protests against Enrique Peña Nieto – started as hashtags on Twitter and other social media platforms. Social media has thrived due to a certain aggression, controversy, and need for expression. According to Del Real, this spirit of dissent, which is the seed of rock, no longer translates into creative expression. “It’s not bad or good; it’s just the way it is now,” he says. “Instead of starting a band, someone will start a blog or a discussion on Twitter.”

Politics have always played a big role in the band; in the past, they have been outspoken in their lyrics. They are also very much politically active as individuals, albeit with different approaches. “Our political stances are very personal,” says Del Real. “We’re all very conscious of what is happening, but each one of us responds in a different way.”

The group doesn’t always agree on these responses. Such was the case a few weeks ago, when lead singer Rubén Albarrán openly declared his support for Delfina Gomez, a candidate for the governorship of Mexico, who is affiliated with the MORENA party, the same one as presidential hopeful Andres Manuel López Obrador.

“Personally, I couldn’t go out and declare my support for any politician,” says Rangel. “But I do think there’s a tabula rasa of things that we have to demand as citizens, which has to do with the laws of our country’s democracy. It’s something I’ve defended since I first voted at 18 years old and marched in my first protest.”

The group has coincided publicly on certain issues, though, as with their controversial decision to stop performing the song “La Ingrata” in response to the femicides that have swept Mexico. This issue has become especially pressing in states like Jalisco, Michoacán, and Estado de México, where the government has issued “gender alert” mechanisms intended to combat violence against women through various protocols. Though it was mostly Albarrán who spoke out against it, the group stood unanimous in the decision.

“I think it’s important to take a stance,” says Del Real. “You can no longer get away with being someone who doesn’t care.”

As the band prepares for a U.S. tour, one that spans over 20 cities (their first in almost a decade), they draw attention to the massive political shifts happening on this side of the border. “You feel fear, you feel uncertainty,” says Rangel. “I’ve heard people say things, like that there’s going to be ICE agents outside of our concerts, and things that sound like a totalitarian state, in a way that I never would’ve imagined the U.S. could be perceived as.”

Café Tacvba first played in the U.S. in 1992. “We noticed certain things back then, like the police having a certain attitude, and whatnot, but this is different. This is personal,” says Rangel. “It’s a shame that in such a powerful country, there is someone who wants to spark fear in people who are here to work, who are only here because their circumstances brought them.”

“You can no longer get away with being someone who doesn’t care.”

Though Jei Beibi isn’t an especially political album, the band does point to one song, which they believe contains a hopeful message. “I think if there’s a political song in the album, it would be ‘1-2-3,’” says Rangel.

The song’s chorus includes the line “1-2-3, cuéntalos bien y si sigues tal vez llegues a 43” (“count them well, and if you do you might reach 43”), an obvious allusion to the murders of the 43 students of the Ayotzinapa Rural Teacher’s College in Iguala, Guerrero. It is one of the darkest chapters in modern Mexican history, though the bubbly, infectious melody might have you thinking otherwise.

“Maybe it’s a naïve or innocent approach,” says Rangel, “but it’s real. It’s about the possibility of things getting better, about how it’s worth fighting to make things better.”

Jei Beibi’s biggest statement is arguably not in its lyrics, though, but in its overall approach. After eight studio albums and countless performances, los Tacvbos have once again demonstrated that they are capable of reimagining new possibilities for themselves, refusing to be weighed down by their past, while looking audaciously towards the future. With the dark panorama that has hit Mexico in the past few years, and a precarious election just around the corner, perhaps that message – one that reinforces the possibility of change – is just the sort of inspiration the country needs right now.

Café Tacvba’s Jei Beibi is out now. Catch them on one of their upcoming U.S. tour dates:

UPCOMING CAFÉ TACVBA U.S. SHOWS

9/14 – Saratoga, CA – The Mountain Winery

9/15 – Oakland, CA – Fox Theater

9/17 – Hollywood, CA – Hollywood Bowl

9/20 – Dallas, TX – Bomb Factory

9/21- Austin, TX – ACL Live at the Moody Theater

9/22-23 – San Antonio, TX – The Aztec Theater

9/24-25 – Houston, TX – House of Blues

9/28 – Miami Beach, FL – Jackie Gleason Theater

9/29 – Lake Buena Vista, FL – House of Blues

9/30 – Atlanta, GA – Masquerade

10/1 – Raleigh, NC – The Ritz

10/2 – Brooklyn, NY – Brooklyn Steel

10/3 – Boston, MA – House of Blues

10/5 – Silver Spring, MD – The Fillmore

10/6 – Charlotte, NC – The Fillmore

10/9 – Denver, CO – Ogden Theatre

10/11-12 – Sacramento, CA – Ace of Spades

10/13 – Fresno, CA – Woodward Park Rotary

10/15 – Los Angeles, CA – Walt Disney Hall (with Gustavo Dudamel and LA Philharmonic Orchestra)

10/17-18 – San Diego, CA – Observatory North Park

10/21 – Indio, CA – Fantasy Springs Resort Casino