The power of literature is so immense that it can change our worldview. Through books, we can see and connect with our cultures and understand who we are. But the dearth of novels by, for, and about women of color has made this impossible for generations of young Latinas. As we continue to cry out for literary heroes we can call our own, we are seeing the tide change a bit. In recent years, books with strong, well-developed Latinx characters have addressed this void. In 2016, Gabby Rivera’s debut novel Juliet Takes a Breath introduced readers to a Bronx-born Puerto Rican teen navigating her identities as a lesbian, woman, Latina, and daughter. That same year, Zoraida Cordova’s Labyrinth Lost gave us a bruja heroine, who finds self-acceptance while on a magical journey to save her family. And Celia C. Pérez’s The First Rule of Punk, which hits bookstores today, follows a Mexican-American punk rocker ‘tween who makes zines and forms a band.

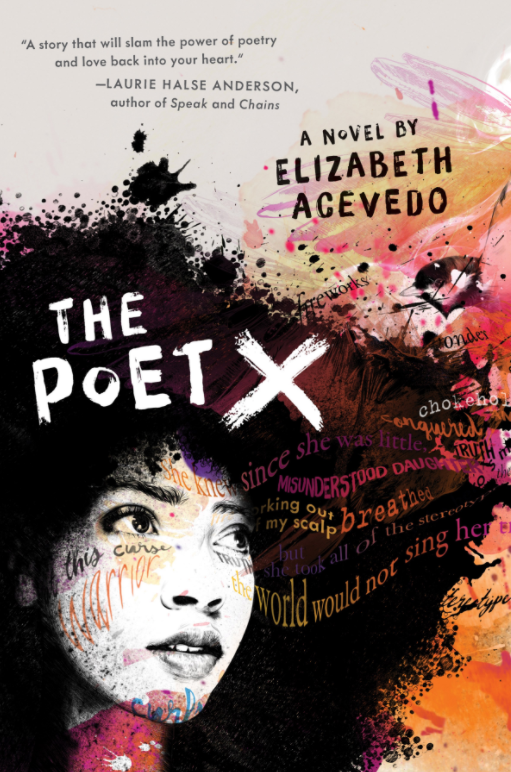

These multifaceted and relatable characters are a breath of fresh air, especially considering that the media still overwhelming depicts our community through tired stereotypes. However, as we see some progress, we’re still missing complex portrayals of Afro-Latinas. That’s where slam poet-author Elizabeth Acevedo comes in. Her debut novel, The Poet X, tells the story of 15-year-old Xiomara Batista, an Afro-Dominican teen growing up in Harlem in a strict, religious household.

Xiomara’s supposed to be preparing for her Catholic confirmation; instead, she’s sneaking around with boys, listening to hip-hop in the park, and going to slams – activities that make her question her faith and cause discord with her mother. To cope, Xiomara turns to writing. Through slam poetry, she tries to find her voice and become the kind of woman she wants to be.

Xiomara’s story is reminiscent of Elizabeth’s. Acevedo is a famed Black Dominican poet from Harlem, who used to rap in her youth. Like her character, she too tackles themes of spirituality, decolonization, and gender norms in her poetry. But the novel isn’t autobiographical.

“Similar to Xiomara, I felt disempowered coming from the neighborhood I came from, and when I started performing poetry, I felt like I was taking some power back. I could push against factors like gentrification or sexism that made me feel so small at home,” Acevedo tells Remezcla. “Xiomara also realizes her power in a very public way, but she’s a bit stronger than I am in how she rebels and stands up for herself. It took me a long time to learn that I could speak up and demand to be treated how I deserved.”

The Poet X – out in early 2018 – is the first of a two-book deal with HarperCollins Publishers. Currently, Acevedo, who’s excited to enter the world of fiction, is working on her second novel.

At a time when political attacks of Latinx immigrants and violence against African American bodies fill the news cycle, coming-of-age stories that help readers make sense of their identities and place in this country are crucial. Of course, The Poet X isn’t the only novel with Afro-Latina lead characters (here’s an entire list of them), but it’s a necessary addition to the collection of Latinx literature.

Acevedo spoke with Remezcla about why she wanted to write this story, the difference between writing slam poetry and novels, and the need for people of color to write their own narratives.

We have edited and condensed this interview for clarity.

Why did you want to write this novel?

I was thinking about how girls are silenced or told, “Tú eres la niña de la casa. You have to cook and clean and be good and get good grades.” But what if you don’t fit that mold, if that doesn’t make sense to you? It’s hard to be the girl you want to be in a culture that raised you to be strong but also quiet. Growing up, I remember my brothers never had to clean, mop, or had a curfew.

“Because of my gender, I was put in this box.”

Because of my gender, I was put in this box. And that was the story of a lot of the folks I grew up with, too. We had such strict ideas of gender roles and what it meant to be a good girl. I wanted this character to challenge that, to complicate and question who she’s told she has to be. At first, you learn the character has been used to using her fists and mollywhopping people in order to get her point across. But I was curious to create a character who learned to use the weapons of her words.

Elizabeth Acevedo, the poet, often tackles issues of colonialism, anti-blackness, feminism and spirituality in her work. What sort of themes come up in this book?

A lot comes up in regards to faith. She doesn’t necessarily subscribe to faith in the way her hardcore Catholic mom does. She questions religion and colonialism. Through that, she’s thinking of what it means to be Latina and comparing what her family and culture allow her to do versus what others are allowed to do. Gender and rape culture are big themes, too, particularly the ways we perpetuate how men and women interact. Friendship and feeling heard or seen in hip-hop are ideas that come up repeatedly in the story. The book is looking at what it means to be young and having teachers and school and television and your homies all telling you who you should be but having to figure that out only on your own terms.

So it’s some of the same issues you take on in your poetry. What are some of the benefits or setbacks to hitting on these themes through prose?

It’s funny because the novel is actually in verse, so it’s still being told through poetry but following one character for 368 pages. One of the benefits is that it’s not me. It doesn’t feel like I’m the speaker, so I don’t have that feeling that I’m trying to impress people like I do when it’s my poem. Or like I’m revealing too much of myself.

“I wish 15 years ago that I had a book where I could fully see and say, ‘that’s me,’ a book that could have helped me answer questions of race and identity sooner.”

This is a different kind of vulnerability. With this, there’s a character, a narrative and the poetry — and all have to balance at all times. You see the development of a person on a page, and there’s action and conflict that have to happen. In my poetry, everything is self-contained. In the poetry I perform and publish, those pieces are self contained. Someone can get the gist of what I’m saying in three minutes or one page. But here, through this project, I need to pace it out over time and engage the reader in an entirely new way. It was an exciting challenge to tackle.

There aren’t a whole lot of YA books centering Latinx characters and even less with Afro-Latinx characters. Why do you think a book like The Poet X is essential, especially in this moment in time?

I think we are starting to see a wave of new Latinx writers creating stories and writing specifically for young people, and we all stand on the shoulders of those authors who told our story before us. But every generation has to own the story of their times, and sometimes publishing is so slow at making sure authentic voices are being uplifted in books and being put into the hands of children.

For me, we are in a powerful moment where a lot of people are interrogating their ethnic and racial histories and complicating the umbrella term of “Latinx.” My character is one of those girls. She’s a self-described morenita who is completely unapologetic when it comes to her hair, and skin, and complicated notions of Black/Latinx womanhood. We are living in a moment where we are talking about Black Lives Matter, thinking about what it means to be Afro-Latina, what it means to be Black and Latina.

For me, this book is saying, “I see you, girl who is called negra at home or at school, who has always had to choose different sides of herself. I see you, and I hope this novel allows you to see yourself.” I wish 15 years ago that I had a book where I could fully see and say, “that’s me,” a book that could have helped me answer questions of race and identity sooner.

What do you hope readers get from this book?

I guess I just really hope readers realize that your story, whatever it is, is necessary and should be told, even if you’re just telling it to yourself. I think when you come from a certain cultural background, or a particular gender, or are gender-nonconforming, or grew up in certain neighborhoods, you’re told you’re an ant in a long line of ants, and none of y’all matter. You’re all the same. You can all be stomped on and no one would mourn not having heard what you had to say. And I just want folks to know that whenever they’ve been told they aren’t good enough, or their individual story doesn’t matter, that’s a false narrative. We all deserve to be written about.

I hope this will be an important story to chronicle this generation. It’s a story about pop culture, dysfunctional families, poetry, bachata, the streets and those first teenage butterflies of crushing on someone. It’s a story that I hope gets the people and place I come from accurately and authentically. I love the quote, “Literature should be both a mirror and a window.”

And so I hope readers will be willing to peek in or peek out with me.