In 2004, more than 300 of Frida Kahlo’s personal objects – including clothing, jewelry and orthopedic devices – were discovered inside of a bathroom in La Casa Azul in Coyoacan, Mexico. Fifteen years later, a selection of those belongings are on display for the first time in the United States at the Brooklyn Museum.

Based on the previous exhibitions, Las Apariencias Engañan: Los Vestidos de Frida Kahlo at Museo Frida Kahlo (2012), and Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up at the V&A London (2018), the Brooklyn Museum’s exhibition focuses on the intricacies of Kahlo’s legacy. As curator Circe Henestrosa states, “It is her construction of identity through her ethnicity, her disability, her political beliefs, and her art, that makes her such a compelling and relevant icon today.”

An interdisciplinary display of art, clothing, and multimedia include examples of her experiences in America, or as she liked to call it, “Gringolandia.” The mannequins are 3D replicas of Kahlo’s measurements, therefore the audience is able to view the garments displayed just as they would have fit on her 5-foot-3-inch body.

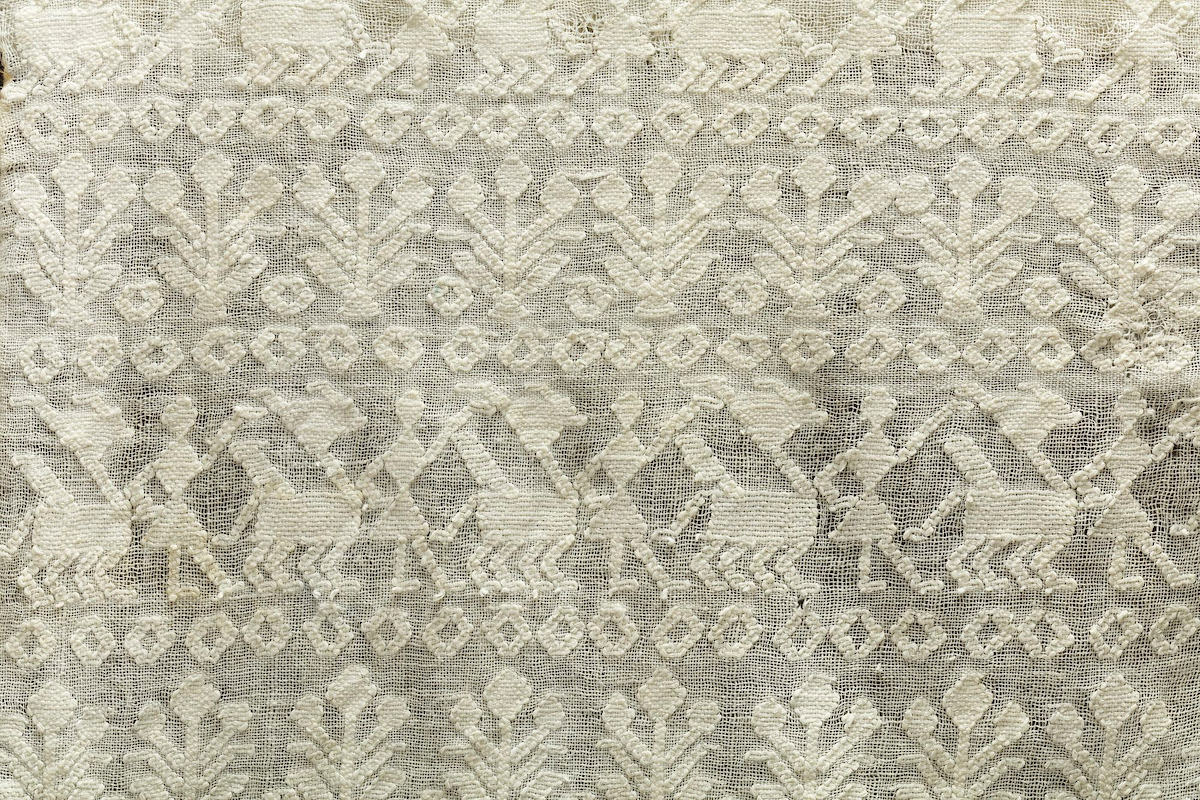

Through her blatant display of Mexicanidad, Frida Kahlo has remained a fashion icon. The traditional Isthmus Dress she is most revered for is based on that of the women of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec region of Mexico, who lead a matriarchal society. Traditional Tehuana dress consists of huipiles (square tops), long loose rabona skirts, rebozos (shawls), and braids adorned with bows and flowers.

However, the multifaceted origins of Kahlo’s garments are noted throughout the exhibition. During the initial unveiling of her objects – hidden for more than 50 years – Mexican anthropologist Marta Turok researched the cultural origins of Kahlo’s pieces, ranging from textiles from Guatemala, Spain, and China, to garments she designed herself.

Due to her physical ailments, Kahlo spent much of her life homebound in La Casa Azul. As she was unable to travel, friends would often visit and gift her clothing and textiles from their own travels she then incorporated into her dress.

Additionally, Kahlo had seamstresses and provided them with designs that attempted to recreate the Tehuana aesthetic using both traditional and contemporary fabrics. Due to the arrival of the Singer sewing machine at the start of the 20th century, varying differences between hand and machine-made embroidery help date pieces and tell where her clothing was made.

Kahlo suffered from two major ailments that affected her lifestyle for the rest of her life. The first was contracting polio at the age of 6 that left her with a shortened right leg, ultimately amputated in 1953. The other, a severe transit accident at the age of 18, broke her collarbone, spinal column, and right foot. As the various examples of footwear, corsets and prosthetic devices she relied on to physically support her demonstrate, Kahlo gained power from clothing, which she also painted and decorated.

In Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Kahlo’s disabled, othered, transnational body is portrayed with full transparency, promoting the notion that fashion, in fact, empowered her, despite her illness. Kahlo chose clothing as a tool with which to compose her identity as more than that of a disabled woman. She consciously disguised her physical appearance through the medium of clothing; incorporating multicultural textiles, designing some garments herself, and modifying traditional Tehuana dress to fit with her desired aesthetic.

In reference to Kahlo’s enduring allure, Latin American Fashion Studies scholar Dr. Alba F. Aragon notes, “Frida Kahlo’s appeal seems to rest largely on a sense of identification; the illusion of her image reveals an innermost truth to the viewer.” As we all navigate the complexities of representation, one cannot help but admire Kahlo’s ability to piece her fragmented identity, including physical disability, through the montage of clothing.