Georgia’s gubernatorial race is making national headlines this year, and not just because if elected, Democratic candidate Stacey Abrams would become the first Black woman governor in the United States. Her Republican opponent, Secretary of State Brian Kemp, is also receiving his fair share of the spotlight – particularly for what critics are calling voter suppression tactics.

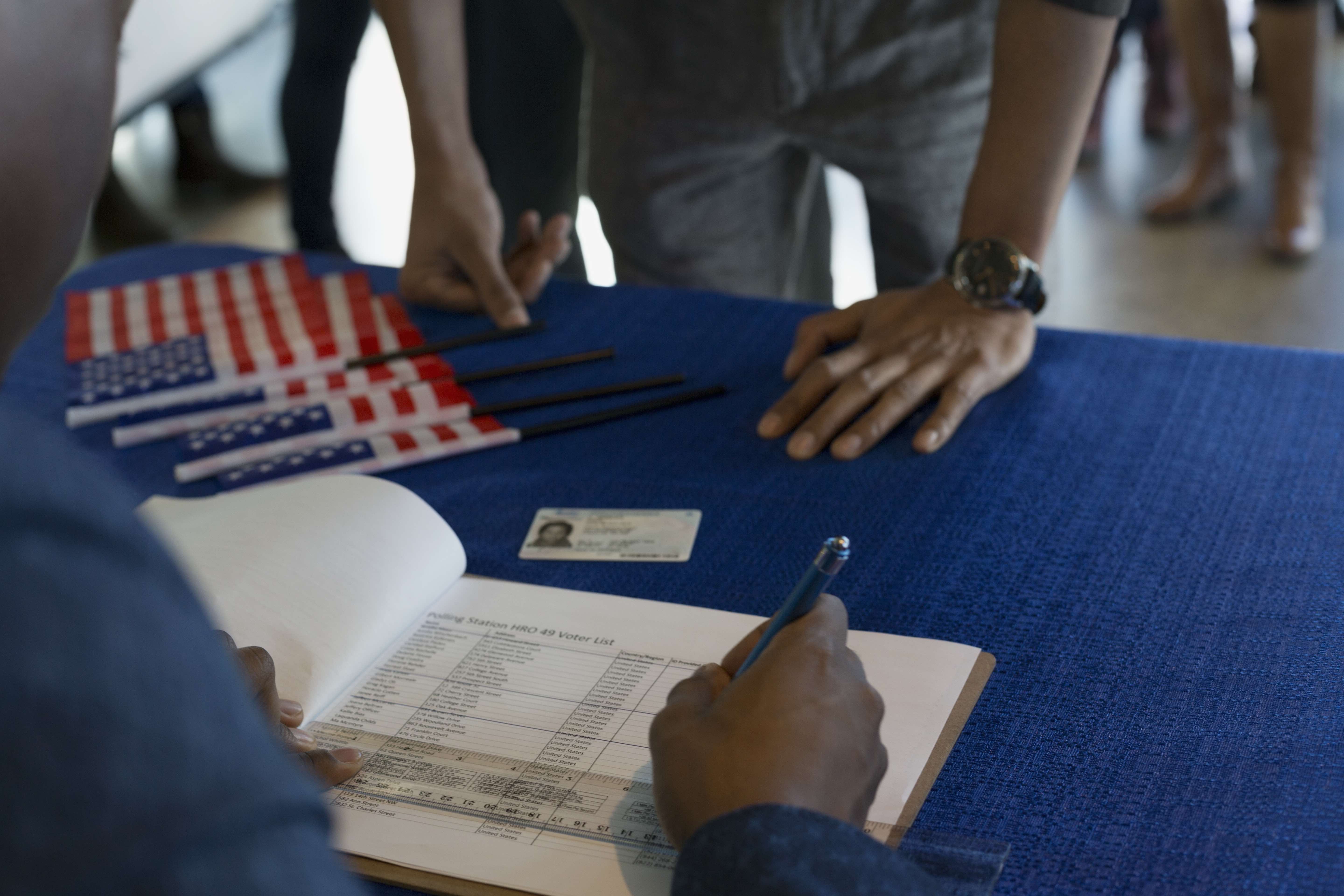

On October 9, The Associated Press reported that Kemp’s office, which is in charge of elections and voter registration, was holding up more than 53,000 voter registration applications, 70 percent of which come from Black voters. The number has since gone down to 47,000 due to duplicates. Kemp’s campaign claims that the holds are a precaution against voter fraud, but studies show that voter fraud is extremely rare and can often be linked back to technical errors.

Kemp has faced voter purge accusations in the past; the Associated Press also found that since 2012, the Secretary of State’s office has eliminated more than 1.4 million voter registrations, almost half of which the office discarded just last year. For voting rights organizations across Georgia, Kemp’s efforts raise serious concerns.

The purges mostly impact Black, Asian, and Latinx voters, especially newly naturalized citizens, because of Georgia’s “exact match” law, according to Brian Núñez – a policy advisor with Georgia Shift, an organization focused on mobilizing millennial voters from marginalized communities. This law requires voter registration applications to match perfectly with their information on file with the Department of Driver Services or the Social Security administrations. Small technical changes, such as a missing hyphen between names, can cause issues with an application.

“Even though they would have the exact same driver’s license number, your social security number, everything is correct, but because it doesn’t match what they have in their system, it’s being thrown out or being held,” Núñez tells Remezcla. He explains that this poses an issue for naturalized citizens who may have decided to make a change in their name during the naturalization process, such as Latinx voters who previously used both a paternal and maternal last name but possibly dropped one of the two upon becoming citizens.

On October 11, a group of organizations including the Georgia Coalition for the Peoples’ Agenda, Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Atlanta, the NAACP of Georgia, the New Georgia Project, the Georgia Association of Latino Elected Officials (GALEO), and ProGeorgia filed a lawsuit to overturn the “exact match” law. The groups testified in court on October 29 about how some naturalized citizens are showing up to the polls to vote with a government ID – all that is usually required – only to be asked for additional documents to prove their citizenship status since it may not yet appear in the system.

“A lot of times, they’re being made jump hurdles that are unnecessary and clearly targeted for those Latinx voters and those that, you know, once they try once – we’ve seen it through data – once they’ve tried once, they don’t vote again. They feel disenfranchised,” Núñez says. For people who make time to vote in the morning or during a work break, having to return a second time makes the process unnecessarily complicated, he explains.

Other than the lawsuit, staff and volunteers from Georgia Association of Latino Elected Officials are making daily phone calls to people on the pending voter list, so they know to take a copy of their naturalization certificate and US passport to the polls, Harvey Soto of Galeo adds. “The problem with that, is of course, we can’t reach a hundred percent of everyone on the list,” he says. “That’s basically impossible, but we try to reach out to as many people as we can.”

In addition to the obstacles faced by new citizens, voting rights organizations are also worried about absentee ballots being rejected at alarming rates in Gwinnett County, which is one of the most racially diverse counties in the entire state. Although CNN reports that Gwinnett only accounts for 6 percent of all absentee ballots in Georgia, more than one-third of those rejected statewide belong to the county – most of which are from Black and Asian voters. Reasons for rejection include missing information, changes in address, and inconsistent signatures, according to Georgia’s Voter Signature Match Law. Multiple lawsuits have been set forth on grounds of absentee ballot rejections, and on October 24, a federal judge ruled that changes in signature cannot be used to discard absentee ballots for the time being.

As they continue to fight discriminatory voter legislation, GALEO, Georgia Shift, and other groups they work with have focused on informing voters about their rights, the fact that all election materials are available in Spanish in Gwinnett County, and that voters are allowed to have someone translate the ballot for them everywhere else. In Hall County, a voter named Gabriel Velazquez says one woman in line began yelling and becoming aggressive with him when she saw that he was translating for another voter, but ultimately, he was able to do the translation so the person could finish casting their ballot.

“During this whole ordeal, the gentleman expressed to me a couple times that language was the reason he considered not voting, but he was glad I was there to help him,” Velazquez says. “I let him know about our rights and told him if any other family or friends need assistance, he can contact me and if I personally can’t help him, I will find somebody to help.”

Anyone who needs help finding a polling place, checking their status, or filing a complaint can call the Georgia Latino Voter Hotline at 888-54GALEO (888-544-2536) to receive assistance from staff or volunteers.