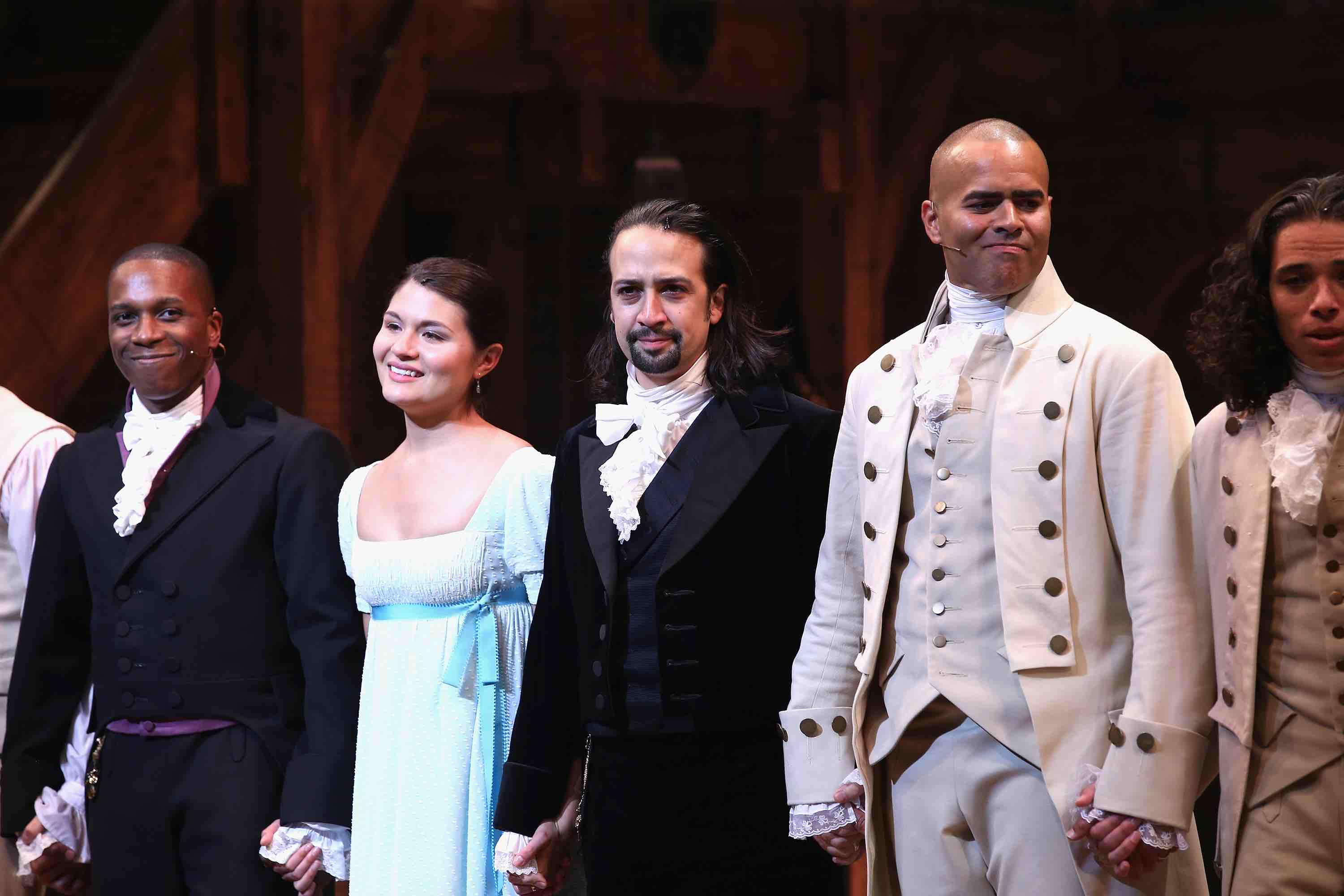

This weekend, Hamilton will make its Puerto Rico debut. Creator Lin-Manuel Miranda will reprise the Broadway show’s namesake role during a nearly three-week run. Along with the award-winning production, Miranda also brings major fundraising, with some ticket sales benefitting his Flamboyan Foundation, which supports arts and culture on the island. Media attention is part of the project, too – the visit is another way to keep struggling island in the news. Jimmy Fallon is even filming a Tonight Show episode in Puerto Rico. Despite the continued attention and love for the Broadway musical, not everyone is excited about Miranda bringing the production to Puerto Rico.

Born in New York to Puerto Rican parents, Miranda vacationed on the island for months during most of his childhood summers. Throughout his career, he has advocated for Puerto Rico, both before and after Hurricane María. There are many boricuas, however, who believe his efforts are misguided.

Miranda’s very public support of The Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) – the 2016 federal law touted as a means of debt relief, which brought with it a fiscal oversight board comprised of seven US-appointed (therefore not elected by Puerto Ricans) members that, since its implementation, has issued budget-reducing austerity measures – figures heavily in the opposition’s complaints.

Under mandate by la Junta, as the board is called locally and throughout the diaspora, the Puerto Rican government has implemented labor reforms limiting sick and vacation days, overtime pay, and holiday bonuses. The island’s electrical authority is on its way to privatization. Some 200 public schools have closed. And the University of Puerto Rico is seeing cuts, too.

But let’s rewind a bit: In order to understand the opposition, there’s a lot to unpack. The show’s well-publicized venue change – announced only weeks ahead of opening night – is an important event to explore.

Originally, Hamilton was slated for a theater on the University of Puerto Rico’s Rio Piedras campus. That’s the same campus that, early in 2017, was shut down by a student strike protesting budget cuts, tuition hikes, and everything else that comes with the Fiscal Oversight Board installed by the federal law PROMESA the year before. It wasn’t the first strike at the school, of course; the university’s flagship campus has a long history of protest, including strikes in 2010 and dating back to anti-military protests in the ‘60s and even resisting the banning of the Puerto Rican flag on campus back in the ‘20s. The University of Puerto Rico has historically reflected the greater island’s issues – these movements represent the people’s perpetual battle against colonialism.

When Miranda first announced that Hamilton would be held at the University theater back in November 2017, students protested, bearing signs that read, “Our lives are not your theater.” They were removed from the event.

But the plans proceeded – and so did contention for Hamilton‘s Puerto Rico run.

In late November, a group of University of Puerto Rico employees called the Hermandad de Empleados Exentos No Docentes (HEEND), currently battling with the university administration against threats to rights and benefits, sent Miranda a letter warning of a possible “major-scale conflict” during the show’s run. But after a discussion with Miranda’s father, Luis A. Miranda, Jr., who acts as a manager of sorts for his son, the group promised to postpone a strike or any other type of organized response until after Hamilton wrapped.

Still, local producer Ender Vega says concerns about security in case of protest that ultimately led the US production team to accept Gov. Ricardo Rosselló’s offer to relocate the show to the Centro de Bellas Artes in the San Juan neighborhood of Santurce. Miranda’s father, a UPR alumni who participated in protests as a student, explained the situation similarly.

The University of Puerto Rico has historically reflected the greater island’s issues.

Whether or not a demonstration would have emerged had the event not moved off campus is impossible to know now, but the HEEND was no viable threat to attendees’ security.

The pro-statehood group Sociedad Civil Estadista Movimiento Ciudadano 51, however, is calling for a demonstration at the Centro de Bellas Artes on Friday; it’s slated to start two hours before the production’s 7:30 p.m. show.

University students are another variable. Many were concerned about the effect Hamilton would have on campus: Would rental payments to the theater, which is a private entity, benefit the university in any way? Was money being pulled from the university’s limited budget to give theater-adjacent areas a facelift by painting buildings and removing trees, several of them hundreds of years old and, according to some students, still healthy? Would the cost of renting the theater – which is a private entity – rise post-Hamilton, making access even more difficult for students?

Moving the show makes suppressing any possible protest easier; police presence on university campuses has been regulated and restricted for decades. But that doesn’t mean the show couldn’t still be affected; opposition didn’t stem only from the venue choice.

University student Maria Celeste Sánchez, president of the Consejo de Humanidades (akin to a department student council), was against the show.

“Knowing full well that the United States has been [Puerto Rico’s] oppressor for more than 100 years,” she says, “and taking into consideration that a lot of the founding fathers were people that owned slaves, people that mistreated Black people, people that mistreated Native Americans and women and all sorts of minorities, and then giving them a minority makeover – a POC makeover, if you will – to try to make them more appealing to another generation, to me, that’s deeply insulting.”

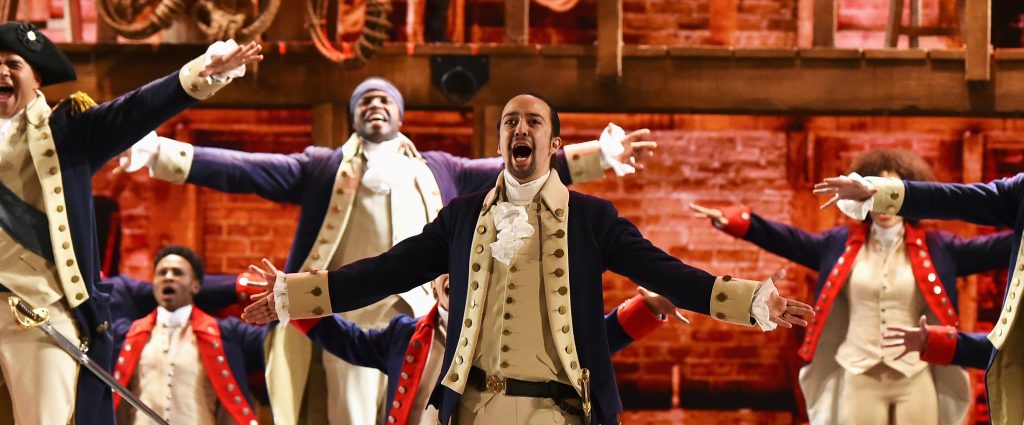

Celeste Sánchez’s opinion echoes a common one among Hamilton critics: That the show’s attempt to diversify the founding fathers story by casting them as people of color – in the original Broadway show, Black actors Daveed Diggs and Christopher Jackson played Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, respectively – softens the reality of that history, especially in terms of racism. (While Jefferson and Washington spoke against slavery, they did participate in it; both owned slaves.)

The portrayal of Alexander Hamilton, previously played by Miranda and later actor Javier Muñoz, as a “common man,” is also problematic for some: Hamilton was a Caribbean immigrant, but as writer Larry Dang notes, he “was a large supporter of big banks” and also supported a monarchical presidency and a Senate without term limits.

“[The money] is going to stay in Puerto Rico, but it’s not really addressing the big issues that we have right now.”

Coincidentally, Hamilton in Puerto Rico is sponsored in part by Banco Popular, the island’s primary banking institution. Independent investigators have questioned the bank’s role in its government’s $70 billion-plus debt.

Miranda’s pro-PROMESA lobbying is another point of contention for students at the university, which has been stretched thin financially for nearly a decade.

Having denied two fiscal plans from the university itself, la Junta certified its own last October which conforms to its continued reductions that, by 2023, will equate to a 10 percent drop in total budget. Tuition and fees have gone up, and costs are scheduled for more incremental spikes each semester.

Sánchez says friends from poor backgrounds have dropped out of school because of the costs.

“Do you know the amount of friends that I know from poor backgrounds that have to drop out of university because they can’t afford it? And people are tired. They’re emotionally and physically exhausted from the hurricane and the strike. And they can’t do it,” she says.

Miranda has since backpedaled a bit about PROMESA: In May 2017, he tweeted, “I was vocal about debt relief for PR…And I think we agree no one is feeling relief.”

Celeste Sánchez and others – like Nina Shakur, a fourth-year UPR student – say that’s not enough.

“He still hasn’t spoken against the Junta or the austerity measures they’re imposing on us, and that is very hypocritical of him,” Shakur says. “If he wants to help, he can use his voice to speak against La Junta, which is precisely one of the obstacles in the recuperation of Puerto Rico post-María.”

Not everyone on the island is against Hamilton, of course. A few days after the venue change was announced, student leaders from all 11 University campuses published a press release asking that Miranda and Hamilton producers reconsider the relocation.

But there are other factors still that have earned Miranda criticism on the island. His other endeavors on the island – namely, his involvement with the Hispanic Federation’s efforts to rebuild its coffee industry, which suffered major losses during Hurricane María – don’t sit well with everyone. Shakur, for one, says he’s “coming to introduce Monsanto seeds which are genetically modified and proven to damage the soil.”

Starbucks, Nespresso, and the Rockefeller Foundation are also part of the five-year project, which does include climate-resistant seeds, but so far there’s no evident link to Monsanto, whose heavy presence on the island is highly contested by many. According to the Hispanic Federation, it’s smallholder coffee farmers they aim to uplift.

Another student, Sofia Melendez, a longtime UPR alum now working through a master’s in biology, wonders if Miranda’s Flamboyan Foundation should be addressing more immediate problems. “[The money] is going to stay in Puerto Rico, but it’s not really addressing the big issues that we have right now,” she says.

Around $1 million was already used to restore the theater after hurricane-related damage, and grants for two major museums (Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico and the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo), a theater company, the Ballets de San Juan, a music initiative on the smaller island of Culebra, the arts nonprofit Beta-Local, and several more.

“It’s like, yes, let’s get money for the arts, which is very important, don’t get me wrong. But I think there’s certain priorities, like let’s fix up schools that are falling to pieces still, a year after the hurricane,” Melendez says. “Let’s fix up the rest of the university that you [planned to use]. Let’s do something a bit more directly practical.”

A recurring theme in young Puerto Ricans’ anti-Miranda sentiments is what they believe is his colonialist perspective, and that he is uninformed about the reality of life in Puerto Rico – a perspective stressed by both Sánchez and Shakur.

Of course, Miranda likely doesn’t see himself this way. His relationship to the island, as detailed in a recent New York Times piece, is a passionate one – but it is complicated.

For Sánchez, the views she holds won’t change without Miranda shifting his own.

“He wants to help the community of Puerto Rico as a whole? He needs to sit down and talk to us and stop coming across as a white savior. Stop coming across as somebody that’s going to save us from ourselves, as somebody that doesn’t want to listen to us,” she says. “He needs to listen through the vitriol, through the anger, so he can get to the source of the problem, and there, he can deal with it. But symbolic gestures like bringing Hamilton here and starting a coffee plantation and bringing Jimmy Fallon here, that’s not going to help Puerto Rico. That’s not going to change anything here.”

Correction, January 11 at 11:35 a.m. ET: This piece has been edited to clarify that Ender Vega didn’t make the decision to move the show to the Centro de Bellas Arte. It was the US production team.