Latinos born in the United States come up against a unique set of challenges compared to directors working in Latin America who often have access to government funding for their projects. The glaring differences are evidenced in the vast disparity between the amount of Latin American movies circling the globe at Class-A festivals compared to Latino ones. If you glance over the lineup for Cannes, Berlin, or Venice you’d be hard pressed to find even one Latinx filmmaker on the list. Meanwhile Mexican, Chilean, Brazilian, and Argentine productions are racking up awards at these same fests. Sundance, with its ever-growing content categories and a concerted effort at showcasing diverse voices, offers only slightly better odds for US Latinos.

Acceptance into a prestigious film festival like Sundance is a badge of honor for directors. It’s fiercely competitive with only a small fraction of the projects submitted granted acceptance. Once you do make it, it’s a pandora’s box of managing interview requests, reading your good and bad reviews, perfecting the art of schmoozing, and maximizing party invites while surviving below-freezing temperatures. For any first-timer it’s an overwhelming experience, but what’s it like for a Latinx director, writer, or producer to step into Park City’s winter wonderland of snowy mountain caps and mostly white audiences?

Amidst the madness of inauguration day, we gathered a group of American Latino creators who’d been accepted into the 2017 Sundance Film Festival for a frank conversation on the obstacles they face — financial, social, and political — when telling their stories.

Marvin Lemus, the director of Gente-fied, a gut-busting web series that illuminates the diversity inside of Boyle Heights’ Latino community and screened in the Short Form Episodic Showcase, was joined by his writing partner Linda Yvette Chavez. They shared the joys of working with Macro Ventures, the production company that funded their series and gave them free reign to make as many references to Juan Gabriel or Walter Mercado as they felt necessary. (Spoiler alert: there’s lots of ’em.)

William Caballero, writer-director of the heartwarming stop-motion animation short Victor & Isolina, and his producer Elaine del Valle spoke openly about how the new President will (or won’t) affect the work they create. Both also emphasized the importance of building a ride-or-die creative team.

Antonio Santini, one half of the directing duo behind the gorgeously shot and tender documentary Dina, opened up about the difficulties of finding commercial opportunities for his previous film Mala Mala and why he thinks this new movie has a better chance. As it turned out, Antonio and his co-director Dan Sickles took home the top award in their category — the U.S. Grand Jury Prize: Documentary — and less than two weeks after its world premiere Dina was picked up for distribution by The Orchard.

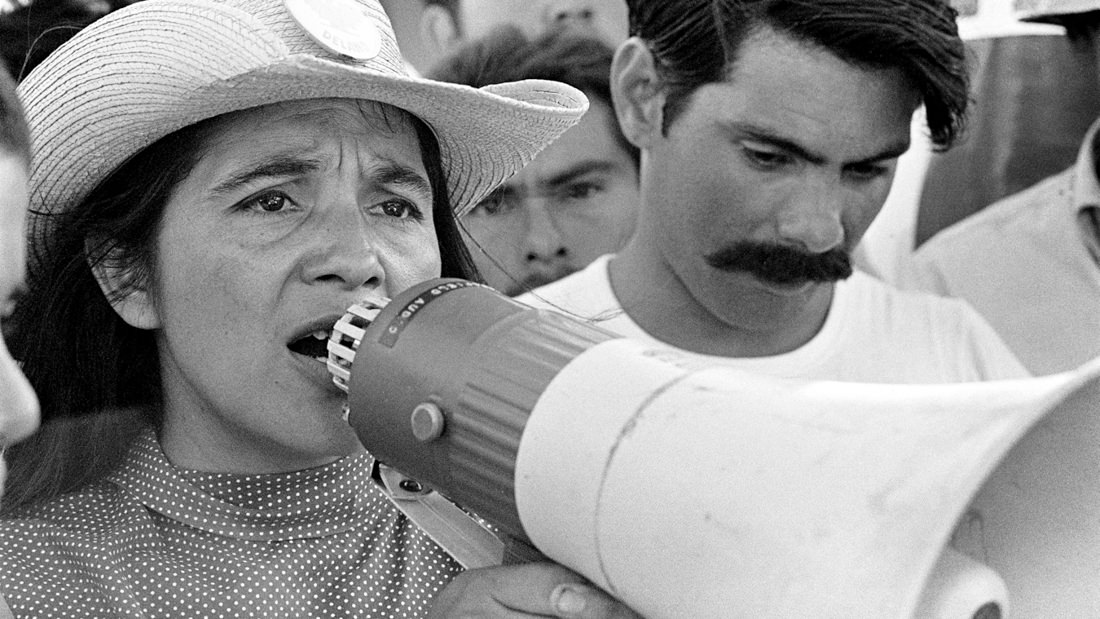

Peter Bratt, the only filmmaker in the group at Sundance for the second time, revealed the name of the angel investor who bankrolled his cinematic homage to activist Dolores Huerta. Containing a treasure trove of archival footage of Latinos fighting for equal rights throughout the decades, the documentary — simply titled Dolores — played in the US Documentary Competition.

Get a bunch of Latinos together and you’re guaranteed to have a lively and heartfelt chat. For this one, no one held back. They spilled it all. There were hearty laughs and even some tears. It got real emotional y’all. Here are highlights from the discussion.

Keep an eye out for our special hour-long collaboration with Latino USA. The episode called Silver Screen airs March 3, 2017 on NPR and will feature audio clips from this conversation. Listen to the Sundance story below and the entire film episode here.

On Finding Support to Tell Authentic Latinx Stories

Marvin: I worked hard to get to the point where somebody would trust me with that damn money! I didn’t have to go around to a million places trying to find financing for this project. It was through relationships that I had built. Macro is a new production company and their M.O. is to create content that features people of color, minorities. Aaliyah Williams (VP of Digital for Macro) saw a short I did. So she asked if had anything. I pitched her Gente-fied and they jumped on it.

Had it been any other company, it would have been a lot harder to get the green light on this. But they understood that this story had to be told, and that Latino characters and Latino storytellers don’t get the opportunities. And it’s because it’s run by people of color.

Linda: Marvin’s really humble. He works very hard as a digital filmmaker. He’s the type of person who’ll run from morning ’til night to make things happen. So the fact that Aaliyah trusted him is for a reason.

What I thought was the most beautiful thing I got out of Macro is their trust and faith in us. I don’t think you would’ve gotten that from anyone else. They were just like, “Go! Be free! Go, be artists!” And we were both like, “For real? You sure you don’t want to look at this draft again?”

That’s why we were able to make something like Gente-fied, which is so pure and unapologetic and subversive and funny. And it’s representing our community in a way that we see them. Versus someone coming in and telling us, “Oh no, this is what the community looks like.” That happens all the time. I’ve been through that, Marvin’s been through that. I’m sure everyone here has been through that. Just being told that we don’t know what we’re talking about, and to add this or change that.

On Fighting the Industry’s Indifference Towards Latino Films

“Thank God for someone like Carlos Santana who put a stake in the ground and said, ‘I will personally bankroll this film.’”

Peter: With La Mission, my brother Benjamin [Bratt] was the star, we had Jesse Borrego, we had known Latino stars, African-American stars. But even with that we couldn’t get any industry support. We were told there’d be no market for it. So we went the independent route and it took 6 years to raise the money. That’s kind of the nature of the beast. Thank God for venues and platforms like Sundance that see the value and power in having diverse stories.

In this case, with Dolores, thank God for someone like Carlos [Santana] who put a stake in the ground and said, “I will personally bankroll this film.” I mean, that doesn’t happen to independent filmmakers. That was a blessing and it definitely opened the gates to creativity and we were able to do this. Without Carlos it wouldn’t have happened.

There is within the industry and the dominant culture [the idea of], “Let’s do some Latino content to tap this Latin market” but I think that’s also confining because the corporations who are funding that kind of content want you to stay within a certain boundary. And that dilutes and confines the Latino experience. We are diverse, we live outside the boundaries. If there’s an attempt to do something that’s even a little bit provocative or challenging, it’s even tougher.

On Pushing Back Against Stereotypes

Linda: I’ll talk about some experiences when I was pitching in rooms that were branded situations — folks who are from companies who wanted branded content for Latinos. What I learned in that process a few years ago is, speaking to that difference between Latin Americans and U.S.-born Latinos, is that they think we’re all the same. They assume that the content that they want is all in Spanish. It’s all a specific type of content and I struggled because I kept bringing ideas and stories that were very U.S. Latino, saying, this is our experience: it’s bilingual, it’s bicultural, it’s multilayered, it’s complex. And sometimes it’s in English! It’s one of the fights that I’m always talking to folks about because it’s about letting people understand that we’re not this big homogenous group of people.

On How the Hustle Pays Off

William: I make sure I work with really strong group of people to make the projects happen. Each project feeds on the success of other projects. My first big project that made me feel like I could be a serious director was American Dreams Deferred, and the first champion of that documentary, who became my co-producer was Louis Perego Moreno who also made me feel that my story was worth something, that it wasn’t just some amateur hobby. He introduced me to what is, to me, the greatest organization of Latino filmmakers and that’s NALIP (the National Association of Latino Independent Producers) who have funded many of my projects since.

I actually received the first HBO documentary grant for $10,000 for American Dreams Deferred which was another big boost for my career. Each project you do adds to your battle chest of experience and it looks good on your resume and your bio. So now getting grants is a bit easier, and I’d say the main financier of this project was an artist grant from NALAC (the National Association of Latino Arts and Cultures). You have to start somewhere, and I think it starts with finding people who believe in you. It’s about creating art and it’s about finding people who want to create that art and be a part of that experience. I could’ve done it without the money, but I couldn’t have done it without the team that I work with.

Elaine: I think all of us, as Latinos or people who have struggled financially, it’s about being resourceful and remembering what we have somewhere out there. Oh yes, I remember, this person. Who can I reach out to? And getting people to get on board. And I think people follow your passion. They will back you if you believe in it yourself. They’re not really backing the project. They’re backing you.

Antonio: Every application we did, you write about your last film and its achievements. So we financed the movie first with Cinereach who is an organization who gave us a lot of money and a lot of support. They are just amazing. They really helped us shape the project, they supported us, they understood our vision and that was what we needed to actually shoot the movie. We had private money, from a private investor who was very supportive. And we had Killer Films and Christine [Vachon] and we had also Moxie Pictures who gave us an office in Union Square so we had a home from the beginning. At the end, Impact Partners came in and became the last investor. We were really blessed with a lot of support. My partner and co-director Dan Sickles is what they call a beast, a boss. He really worked so, so hard on the financing aspect. We’re a team; we direct and produce together. And I can’t imagine doing it alone.

On Championing Publicly Funded Arts Programs

William: When the government and the powers that be seem to be pushing an agenda — or seem to saying, “Your stories don’t matter, we don’t care about your sexuality, we don’t care about this, we’re going to look at cutting down arts programs which are set to tell diverse stories” — that does affect me as someone who has gotten my short film funded by an organization that receives funding from the government.

“We’re faced with an administration that seems hostile to diverse voices and filmmaking. I’m worried, but I’ll still create. It’s the only thing that we can do.”

I think that in this country, a lot of conservatives think that we don’t need funding for films. We have Hollywood! It’s a private enterprise! But we know what Hollywood movies are like. Yeah, some are great, and some are touching and some are diverse. But some are absolute garbage.

I think one of the last bastions of true independent voices in my opinion is PBS and the CPB. These entities that are really showing you don’t need to have money to tell a story. And that’s what I feel is sadly going to be happening is that the person with the biggest wallet is the one that’s going to be telling the biggest stories.

This is art, filmmaking is art and to some degree it needs to be funded by the government. We’re faced with an administration that seems hostile to the very notion of diversity, to diverse voices and diverse filmmaking. I’m worried, but I’ll still create. It’s the only thing that we can do.

On the Power of Cinema & Aiming to Reach Different Audiences

Antonio: I started to understand more and more what the medium can do. I started to understand that it can be an agent of change. When we started to make Mala Mala, which is my first movie, we shot it out of my parent’s house. We lived at the house for like three years. My mom never saw anything. She didn’t want to watch it until the end. Puerto Rico, at that time, was very anti-trans, very anti-gay. At night we would travel to go film and my parents were really worried for us that we were going to get hurt. When the film premiered at Tribeca, when my mom for the first time saw it, she understood.

I wanted to make a movie that was very Puerto Rican and I wanted to make a movie that celebrated my community. So now Dina, which premieres tonight, this movie is very American. I knew after Mala Mala and the commercial difficulties of it, that making something that on the surface was very American and all in English with white subjects was going to help me talk to the world in a way that would be more amplified. I understood that the subjects from my last movie — a lot of people didn’t want to give them the time to even listen to them. Having the movie being half in Spanish and half in English it presented difficulties. So getting into Sundance [with Dina], has just shown us that we were right.

On Taking Pride in Our Latino Identity

Peter: This color: moreno, cafe, whatever you want to call it, brown skin. This color did not come over on the Mayflower. Or on Columbus’ ship. This color is indigenous to this western hemisphere. But part of what happened in colonization is that in order to become oppressed, the colonizer had to strip away identity. And replace it with shame. Many of the farmworkers, you look at their faces: they’re indigenous people. But if you strip away identity it’s easier to take possession and take the land. So to me, identity is so important.

So to me, these identities and overcoming the shame that we were taught, it goes back generations — to be ashamed of our color. In Latin America, to this day, you want to insult someone, you say “puro indio!” It’s like the n-word. So to overcome that and reclaim it was very powerful.

On Navigating Politics in 2017

Elaine: I don’t think that politics takes place in the films that I want to write or produce, or the people I want to work with per se. It’s always been important so my mission is not going to change. I believe that if people are feeling a certain way or depleted by something that they will rise to the challenge. If you don’t have the money for something, you will get the money for something that you need. Because you need to get there. And that’s your own drive that’s making it happen. So the challenge is that this administration may pose to Latino filmmakers, or anyone for that matter, I think that any challenges that come our way as individuals, it is our responsibility to find the reason why that challenge was set before us and to now get around it, stand above it, jump over it, anything that we need to do.

On Using Art as Social Activism Against This New Administration

Marvin: I feel like now, more than ever, as a Latino, as a brown man… to put in as many brown fucking faces as I can on the goddamn screen. I think it’s because when we are being called “illegals” and “rapists” and “murderers” you’re dehumanizing us and our entire experience.

“I grew up wanting to be white. I grew up rejecting my culture. I grew up rejecting who I was. Hating myself. It’s because I didn’t see myself on the fucking screen.”

The reason we have such division is because we have half of this fucking nation that doesn’t see us as people. And they don’t see us as people because we’re not represented on the damn screen. For me, the responsibility now is to tell my stories and to create that access and allow as many POC and minorities to tell their stories.

I know firsthand what it means to not be able to see yourself on that screen and to feel like you are less than. I grew up wanting to be white. I grew up rejecting my culture. I grew up rejecting who I was. Hating myself. It’s because I didn’t see myself on the fucking screen. I know how important that is. If it’s that easy for me to feel that way, how can I expect anybody that is not of my culture, or any white person, to see me? That’s what I put my lens on. To put it on people of color, on minorities.

Linda: This is hard. It’s a hard transition. I’ve put all of those feelings aside because I’m not gonna be sad at Sundance! But today is a hard day. Basically what Marvin said: my art is my social activism. It’s how I try to create social justice for my community, for my people. But I also feel like art is a source of healing in our community.

I feel like I was born to do this. It’s my responsibility to do this for the people I love. It’s a gift and a talent that I feel was given to me to create change. People aren’t gonna fight for you always and you’re gonna have to fight for yourself. I was raised by a ton of luchadoras. I am a guerrera through and through. With my art it’s the same thing.

Those of us who are born of immigrants or who are undocumented, we’ve experienced very harsh judgment from so many people and specifically this administration and this person whose name I will not speak. But the way he’s spoken about us is not new people!

People saw that and were outraged, but we grew up hearing this shit! People calling us these things and telling us to go back to where we came from and seeing our parents being told that. This was our experience growing up. We grew up poor and having to defend ourselves and our families. We grew up having to fight to believe that we were worth loving. That’s where our art comes in, to say: “We don’t need you to validate us. Fuck you! We validate ourselves, and these are our stories.”

Editor’s Note: Due to scheduling constraints, Peter Bratt’s interview was conducted separately from the group.