Baile funk is one of the biggest Brazilian cultural phenomenons of today. However, despite the success, the millions in income it generates, and the various artists who share the top of the charts (like the now world-famous singer Anitta), it’s still a musical style that is severely criminalized and persecuted. The genre receives backlash due to its origins (favelas, or slums of Rio de Janeiro), demographics (being a musical style of Black origin), and by one of its substyles, the so-called “Proibidão” or “strongly prohibited,” having as background the praise of crime (very similar to the Mexican narcocorrido or even the samba in its origins and American hip-hop).

In the beginning of the 20th century, another highly popular musical style, samba, was also heavily persecuted. Sambistas were arrested and were even victims of violence for singing the rhythm that quickly became one of the main symbols of Brazil, especially Rio de Janeiro.

“Until the 1940s, samba was restricted to the hills, [favelas], and the suburbs of Rio de Janeiro, as a localized phenomenon associated with marginality, ghettos, the Black [community], and poor population,” musician Makely Ka tells Remezcla. “Samba, in its origins, was associated with subversive activities,” even though the rhythm was not, in itself, criminalized.

“Samba built around itself a certain association with mischievousness, which in the early years of the republic was enough for practitioners of the genre to become targets of the so-called Lei de Vadiagem [Vagrancy Law], capable of even putting anyone with as much as a guitar behind bars,” explains Gabriel Borges, Ph.D. student of literature, focusing on Brazilian music at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

Borges belives that “samba emerges as a by-product of the abolition of slavery, associated with the Afro-Brazilian experience that as such were demonized by the white landlord and, once freedom was achieved, remained marginalized in their social condition and criminalized by law.” But, as Ka adds, “With the passage of time [samba] became consolidated as a national rhythm, including the official campaign of the government in the Vargas era [in the 1940s].”

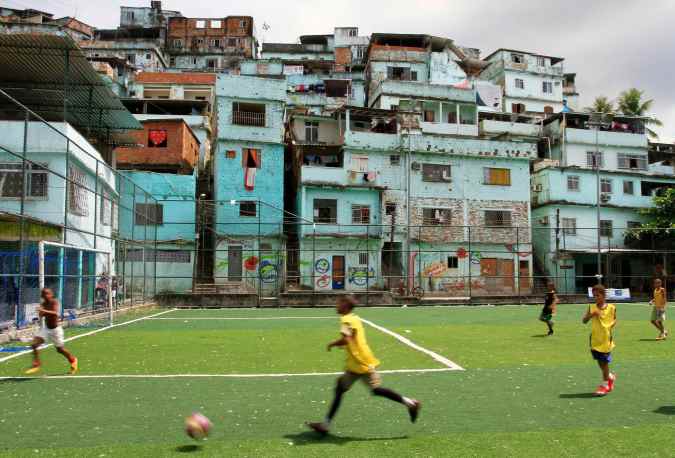

Samba was born as an instrument of social contestation, with lyrics about the situation of the favela resident – victim of prejudice and violence. It was and still is a representation of the aspirations of a marginalized part of the population to integrate into society, a phenomenon that should be understood as “resilience” rather than as a contestation, says musician Antonio Spirito Santo. Funk is not very different.

From “proibidão,” to funk with lyrics of greater sexual appeal, to the so-called “funk ostentation” – which preaches luxury and wealth in a way similar to some American hip-hop – a musical style born in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro spread throughout the country, and with remarkable variations in style.

But regardless of style, those who are dedicated to singing, dancing, and promoting funk often end up victims of violence and police harassment. Bailes [parties] are criminalized in favelas, often shut down with extreme violence by military police. The most recent case is that of Rennan Santos da Silva, or DJ Rennan da Penha, creator of “Baile da Gaiola” [Cage Party], a funk party that brings together about 25,000 people on weekends in Vila Cruzeiro – a favela in Complexo da Penha and producer of some of the biggest recent successes in the world of funk music.

On March 18, DJ Rennan da Penha, was sentenced along with 10 other people, to six years and eight months in prison (after being cleared in the first instance) for association with drug trafficking. To the judge, the baile promoted by Rennan was “pro-crime” based on posts from social media, and on the fact that, on February 16, Rennan warned people that the military police would be going up the favela to end the party. In fact, there was a shooting and five people were injured.

His lawyers and activists claim that the justice’s decision was racist, and seeks to criminalize funk as it is common practice for favela residents to pass alerts through social media and WhatsApp, alerting others of the presence of the police so that they could leave the front line, and not be targets of abuse and violence.

If we take into account the history of funk (and that of samba), the claim does not seem absurd. On the one hand, you have those funk singers who were able to become successful in the mainstream, betting on lyrics with little or no socially critical content. On the other hand, you have those who remained in the poorest communities of Rio de Janeiro, living with drug trafficking, militias, and violence, whoe end up being treated as criminals for merely living in the same environments.

Borges says, about Samba, that “on the one hand, the marginal side of the genre had in Black slavery one of its foundations. No wonder the urban samba initially approached the figure of the scoundrel [or vagabond], whose refusal to work is due to this social trail inherited from the exploitation of slave labour. On the other hand, the genre also represents abundantly the aspirations of Black sectors to integrate into [white] society, trying to overcome this same marginalization,” and to some extent the same can be said about funk – a marginalized musical style that, as mentioned by Spirito Santo, is also a way to integrate into a mostly white society. At the same time, it’s a form of resistance, and is even revolutionary to the extent that the very survival of the young Black man is a form of political resistance. To anthropologist Orlando Calheiros, even the lyrics with heavy sexual content are a “mechanism of resistance and insurgency” against the patriarchy.

“Funk is the celebration of jouissance of the oppressed, and such jouissance is also sexual,” which ends up defying the moralistic views of the mostly white middle classes, “those subjects who have their sexuality marginalized, oppressed, sexual jouissance is a jouissance of resistance,” he adds.

In 2017, a bill was presented to the Brazilian Senate seeking to criminalize funk and make it illegal on the grounds that it would be a “false culture.” It also stated that bailes served to commit serious crimes, from drug trafficking to rape. The bill was rejected even before it was voted on, but it makes clear how the musical style offends a significant part of the population that is willing to criminalize the greater representation, today, of culture coming from the periphery of big cities like Rio de Janeiro.