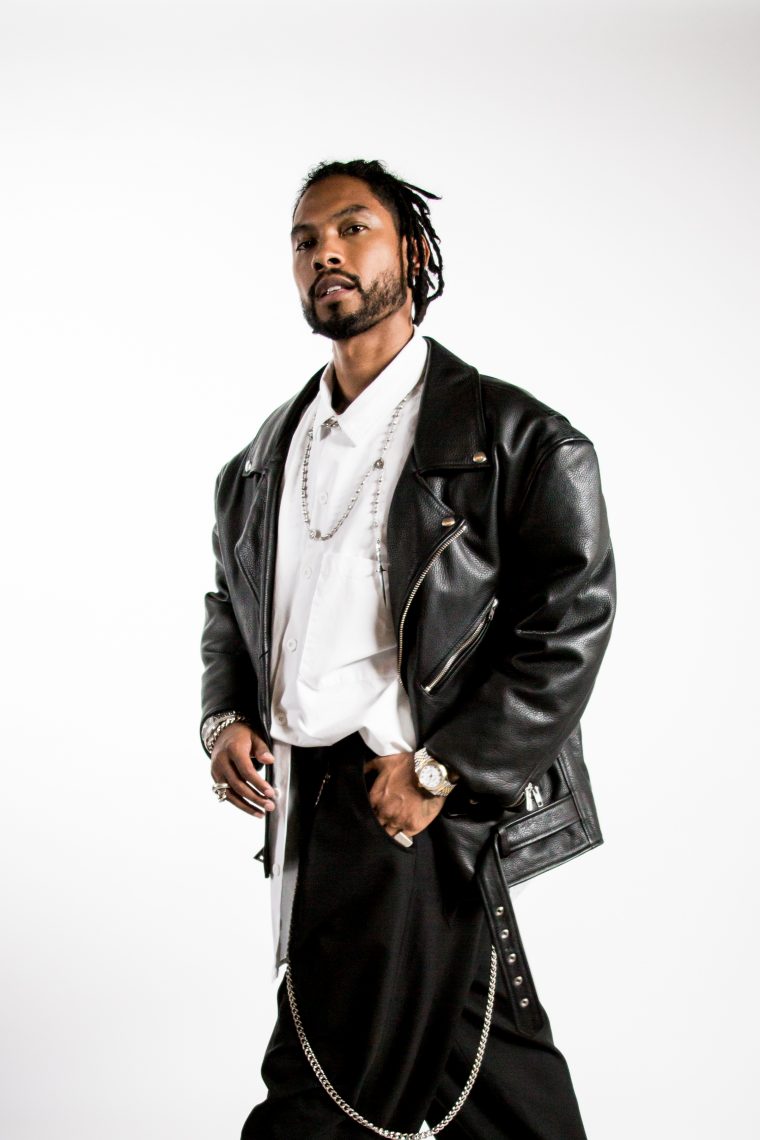

Styled by Marcus Correa

Photography by Michael Perez

It’s after 2 p.m., but the steak tacos Miguel is about to devour are his first meal of the day. “I try an intermittent fast,” he says. He’s seated at a long wooden table across from me in Remezcla’s Bushwick offices, casually picking at the carne asada in front of him and sipping on a bottle of water. “Our bodies are designed to heal themselves,” he elaborates, launching into a lengthy explanation that references neurons, electrons, and the pH level of the water we drink. I don’t quite follow it all, but I’m back on board by the time he concludes, “I try my best to eat more plant-based, but sometimes, you know, I just want steak tacos.”

It’s late summer, and he’s dressed in a slightly unbuttoned tropical print shirt, oozing effortless charm and playing up the sex mystic persona he’s cultivated through his music. But Miguel is disarmingly friendly, and his goofy jokes about my septum piercing suggest he doesn’t take himself too seriously. He is mellow but forthright, speaking earnestly about his journey to this moment, the release of Te Lo Dije, a 5-track EP of Spanish-language versions of songs from his last album War & Leisure. It is the culmination of a decades-long return to his roots.

Born to Mexican and Black parents in California, Miguel Jontel Pimentel was raised between Inglewood and San Pedro. Like so many Blaxican kids from South Los Angeles, he grew up between cultures and identities: two homes, two languages, two realities. “A lot of my knowledge of Spanish comes from speaking Spanish with my grandparents and my aunts and my tíos and my tías in Inglewood over the summers, and when I visited my father’s side of the family,” he shares. Miguel regrets not being able to practice his Spanish in between these visits, a consequence of existing as a child of divorce; his father and mother split when he was eight years old, and he spent the school year at his mother’s home in San Pedro.

“I grew up in Los Angeles in the 90s,” he says. “[As] teenagers we weren’t listening to music in Spanish. We were listening to rap, you know? We were listening to Tupac and Biggie and what was going on at the time – 112.”

Still, speaking the language was always a pivotal part of his identity – one the music business didn’t always understand. In the beginning, Miguel says industry bigwigs and label heads struggled to understand the intersection of blackness and Latinidad, questioning his name and appearance. “It was definitely a point of, ‘Huh? We don’t really get it,’” he remembers. “A lot of my audience didn’t know I was Mexican.” As he put it in an interview with Viceland, “Most people think of me solely as a black artist, but there’s a reason why my name is Miguel.”

It’s a reality that plenty of black Latino pop stars have had to contend with in a system that renders complex identities into monolithic and palatable packages. At the end of the day, Miguel says his focus has always been about creating art that makes him feel whole.

“I think my music could speak to a lot of people and say things for a lot of people. They just haven’t really found it and discovered it yet.”

Luckily, he has gradually been able to crumble these boundaries over the course of his career. On his 2015 opus Wildheart, he sang in Spanish on the interlude “destinado a morir” and posed provocative autobiographical questions on “what’s normal anyway,” declaring, “Too proper for the black kids, too black for the Mexicans” in the song’s opening line.

Wildheart cemented Miguel as a critical darling and a rebel among his R&B peers. At the time, his counterparts dealt in self-centered sadboy odes to sexual pleasure. Instead, Miguel embraced his role as an acolyte of forebears like Prince or Marvin Gaye, serving lethal grooves of retro psychedelia about the power of erotics as a vehicle for self-discovery.

On his follow-up album, War & Leisure, Miguel doubled down on that strategy, weaving tales about punch-drunk love with subtle political references. Its title is an attempt to capture the experience of living in a time of political disillusionment, with misty-eyed missives like “Now” sitting alongside carnal come-ons like “Come Through and Chill.” Those political allusions might not be immediately visible, but the power of Miguel’s music has always lied his ability to articulate his politics in simple, but potent ways, and they begin to answer some of the questions he raised on “what’s normal anyway?”

“It says a lot about what I represent,” he observes about the Wildheart track. ”[About] what I come from. It’s like the a-ha reason, the a-ha moment for anyone that doesn’t know [me].”

Miguel’s life has been full of these a-ha moments. A recent one took place in 2017, at a radio station in Zamora, Michoacán. There, alongside his brother and father, he sang an aching rendition of the bolero “Contigo,” composed by the famed trio Los Panchos. He had come to find the Mexico he’d been missing, and in that moment, he did.

It was a repatriation, and one that had been a long time coming. Visiting that radio station was the first time Miguel had ever traveled to Mexico or met the Mexican side of his family. La Catedral de la Música 91.7 is the former workplace of his abuela Clara Pimentel, who immigrated to the United States decades earlier to escape poverty, working as a housekeeper in the L.A. area to make a better life for her family. It was then, while harmonizing to a melody beloved by his ancestor, that he was able to understand the ways in which the sacrifices of prior generations have shaped him as an artist.

“From now on, I just have to write more in Spanish and create more music in Spanish. It was just important.”

“It didn’t hit me until I went back, until I was with my father and brother in that radio station in Michoacán where [my grandmother] used to sing,” he says. “Even if the building was different or had evolved in some way, she was here and she left this, something she loved. Her passion somehow was passed down and here I am.” He pauses, struggling to find the words that harness the power of this moment. “That shit – I can’t tell you the feeling. You start to think about the sacrifices that you being alive requires, and all of the things that lead up to that. It was the fact that my grandmother left, went to live with my aunt in Inglewood, and my father grew up in Inglewood, went to Inglewood High, and met my mother in Inglewood and that’s why I’m here. You think about the layers of her passion for music and her giving that up for family,” he says pensively.

Miguel’s musical roots were planted in Michoacán even before he was born, and as he describes it, his return there compelled him to make more music in Spanish. “I was able to meet family that I didn’t even know about, but I felt connected to them. To meet somebody you never met and it be like, ‘Wow I feel like I’ve known you forever. You know me,’” he says. “That was pretty much it. I was like, ‘From now on I just have to write more in Spanish and create more music in Spanish.’ It was just important.”

Miguel’s decision to flip songs from War & Leisure into Spanish is the product of a years-long journey to connect with his Mexican identity. But there’s no denying the advantage of his timing, given the Anglo music industry’s renewed interest in mainstream Spanish-language pop.

The lucrative possibility wasn’t lost on Miguel’s record label. Way before the Michoacán trip, Sony Music Latin chairman Afo Verde approached Miguel about recording in Spanish. “We met a few years back during Wildheart and he always was like, ‘If you ever want to do something in Spanish, let me know,’” he says. After his return to Mexico, he decided it was the right time. “Afo helped me with the translation process, understanding that obviously there are so many different dialects in Spanish,” he shares. “We got translations from different dialects of Spanish for different songs.”

While Miguel worked with Verde on some tracks, he also recruited a pair of longtime friends and collaborators: Dante Spinetta and Emmanuel Horvilleur of the Argentine duo Illya Kuryaki and the Valderramas. The trio had previously joined forces for “Estrella Fugaz,” a thick psychedelic groove from IKV’s 2016 album L.H.O.N. When the chance to work on a handful of songs emerged, Spinetta and Horvilleur jumped at the opportunity.

“I believe he has a great opportunity being able to sing in Spanish,” Spinetta, the son of Argentine rock legend Luis Alberto Spinetta, tells me over the phone. “He’s a unique artist, he can bring something different to the game. We talked a little about that, about the beauty of it, about how good the culture clash that’s created is. Those of us that make music in a [hybrid] way – these are things we dream about,” he says.

Miguel’s choice to record in Spanish remains fiercely personal. For him, it isn’t much of a political statement; it is more about ensuring that his art resonates with everyone in his community, no matter the language. “I think my music could speak to a lot of people and say things for a lot of people,” he says. “They just haven’t really found it and discovered it yet. So I’m always looking for new ways to reach those people and to build a relationship with them.”

Of course, there will be those who view the decision through a more cynical lens. Now that the chart-topping success of Spanish-language music has validated Latino artists to industry gatekeepers, some critics suggest that artists who are just starting to embrace their identities are only riding the wave. But this perspective ignores the journey so many bicultural kids take to understanding themselves, as well as the stigmas that we have to unlearn around our identities. And of course, there’s the fact that the exorbitant popularity of Spanish-language music may be encouraging for artists who never thought they’d be able to succeed doing it.

Ultimately, Miguel is adamant about establishing that he’s been on this path for a long, long time. “I only do things that feel real to me. So even before taking the trip to Mexico, before visiting my family and getting a little more acquainted with my roots, I was including Spanish in my records because it was natural. I included the amount that felt natural,” he says, referencing the interlude on Wildheart. “Am I capitalizing on the fact that I can speak Spanish, that I really am Latino, that I create and I’ve created in Spanish, and that I think that my music is relevant to people who speak Spanish?” he asks. “Yeah, I guess so. But is that wrong? I don’t feel bad about that,” he says firmly. “I wanted it to be authentic. Really, at the end of everything, I just wanted to be authentic. I wanted it to be with purpose and to feel real and to feel right.”

Thankfully, Miguel sounds triumphant en español. His sweet nothings and smooth-talking metaphors find a welcome home in the poetic contours of the language. There’s a certain freedom and flexibility we haven’t heard from him before, and a sense that he’s finally letting go.

On Te Lo Dije, he tapped C. Tangana for a new rendition of “Criminal,” bringing the Spanish bad boy closer to the brink of his global moment. There’s even a previously unreleased feature from Kali Uchis on “Caramelo Duro.”

But the most masterful reimagining here is his collaboration with his real-life, half-Dominican cousin Mireya Ramos of the women’s mariachi group Mariachi Flor de Toloache. The primos remade “Told You So” into a gorgeous symphony of diasporic longing, tethered to the tradition of bachata and ranchera. Miguel says he and his cousin have discussed creating visuals to accompany the new rendition.

Ramos’ father sang with Miguel’s grandmother and her sister on the radio station all those years back in Michoacán, and to reimagine the song into “Te Lo Dije,” the primos linked in a studio in New York, along with his tío, Mireya’s father. “We sipped tequila, and we laughed and we cried, and we hugged, and it was like a family reunion over music,” he laughs. “That was special because he got to reminisce a little bit and tell me about how things were with my grandmother, because she’s since passed, transitioned. In those moments, things come full circle and you start to see the fruit of the seeds the planet planted decades ago. Seeing someone else in other people’s visions and their passions come alive through you,” he says, quietly reflecting on his connection to his forebears, and the sacrifices his grandmother made to land him in this stage of his life.

“My grandmother’s intentions and her passions, they’re all put into her action to come to the United States and to build a family with my grandfather. And obviously her sister and brother had similar passions, and at the same time, had to make real hard decisions. And in all of that, that’s where Mireya and I are the manifestations of their energies and their intentions,” he says.

It’s clear that Miguel has used his own family’s immigration story and their experiences to inform his approach to political activism. He has long galvanized communities to organize around immigration; in the fall of 2017, Miguel performed at a benefit for the Adelanto High Desert Detention Center, which holds about 2,000 detainees from Mexico, Central America, and Haiti. Then, at the beginning of 2019, he joined Brooklyn Defender Services, RAICES, and the ACLU of Southern California in a campaign aimed at fighting family separation and providing Central American immigrants with funding for day-to-day needs and legal fees as they await updates on their cases. Although Trump issued an executive order to end family separation in June of last year, according to recent reports, the policy is still functionally in place, and the effects of the cruel practice are still reverberating across the country.

“Emotionally, they will never be the same,” he says about the Central American youth who are currently in limbo. “When children are separated from their parents at an early age, that creates anxiety; it creates problems with self-worth; it creates problems with self-esteem. And these kids will never know a normal life, at least in that way.”

“We sipped tequila, and we laughed and we cried, and we hugged, and it was like a family reunion over music.”

Miguel is adamant about trying to underscoring that the issue is a matter of survival and humanity, no matter the background. “People are fleeing really adverse situations. Either it’s dangerous and they have to leave and there’s no opportunity to provide for their family. There’s a number of reasons why people will travel and put their lives on the line with their children. They’re trying to survive.”

“It’s not just the fact that I happen to be Mexican and my family’s Mexican,” he continues. “Maybe it strikes more of a nerve for me on an emotional level, but it’s the principle, right? This is wrong.”

Despite how certain he is about the inhumanity of the country’s continued hostility towards immigrants, he admits that his ideas for how to address this trauma are still evolving. “I’ve been starting to settle into my perspective on the world, and trying to figure out how I can contribute. When [War & Leisure] came out, I was kind of at the very beginning of realizing that, ‘OK, I do feel a sense of responsibility and trying to figure out what that means for Miguel.’ It’s clear more and more every day to me that I want to focus more on the human condition…how we treat each other, how we treat ourselves are what are important to me. Because unfortunately, the infrastructure of politics are just so tangled, especially in the United States. The way that things are connected in terms of business and politics — that infrastructure is really dense.”

At the end of the day, this sense of immediacy and activism will continue to shape the next creative chapter of Miguel’s career. Whether he’s addressing immigration issues or embarking on the next step of returning to his roots, Miguel’s longstanding search for an authentic sense of self, for a sense of dignity and totality as an artist, continues. For some time now, he has desired to be seen for who he is, as he is.

Stream Te Lo Dije on Spotify or Apple Music now.

Production Credits:

Makeup Artist: Jenna Drudi

Photo Assistant: Iris Laloiwe

Creative Director: Alan López

Photo Editor: Itzel Alejandra Martinez

Video Teaser: Juan Luis Espinal, Rodrigo Olivar and Rafael Urbina

Artist Relations: Joel Moya