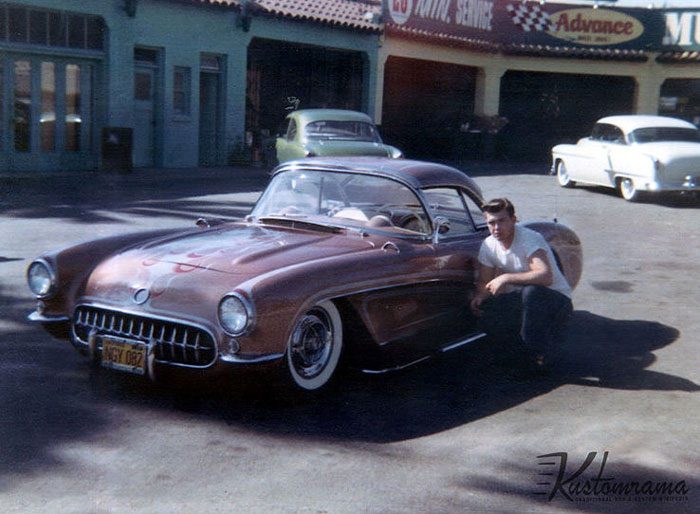

From the streets of Tokyo, where Japanese self-styled cholos practice their Spanglish, to São Paulo, where residents have created their own thriving version of an East LA car scene, lowrider culture has traveled a long way from its SoCal origins.

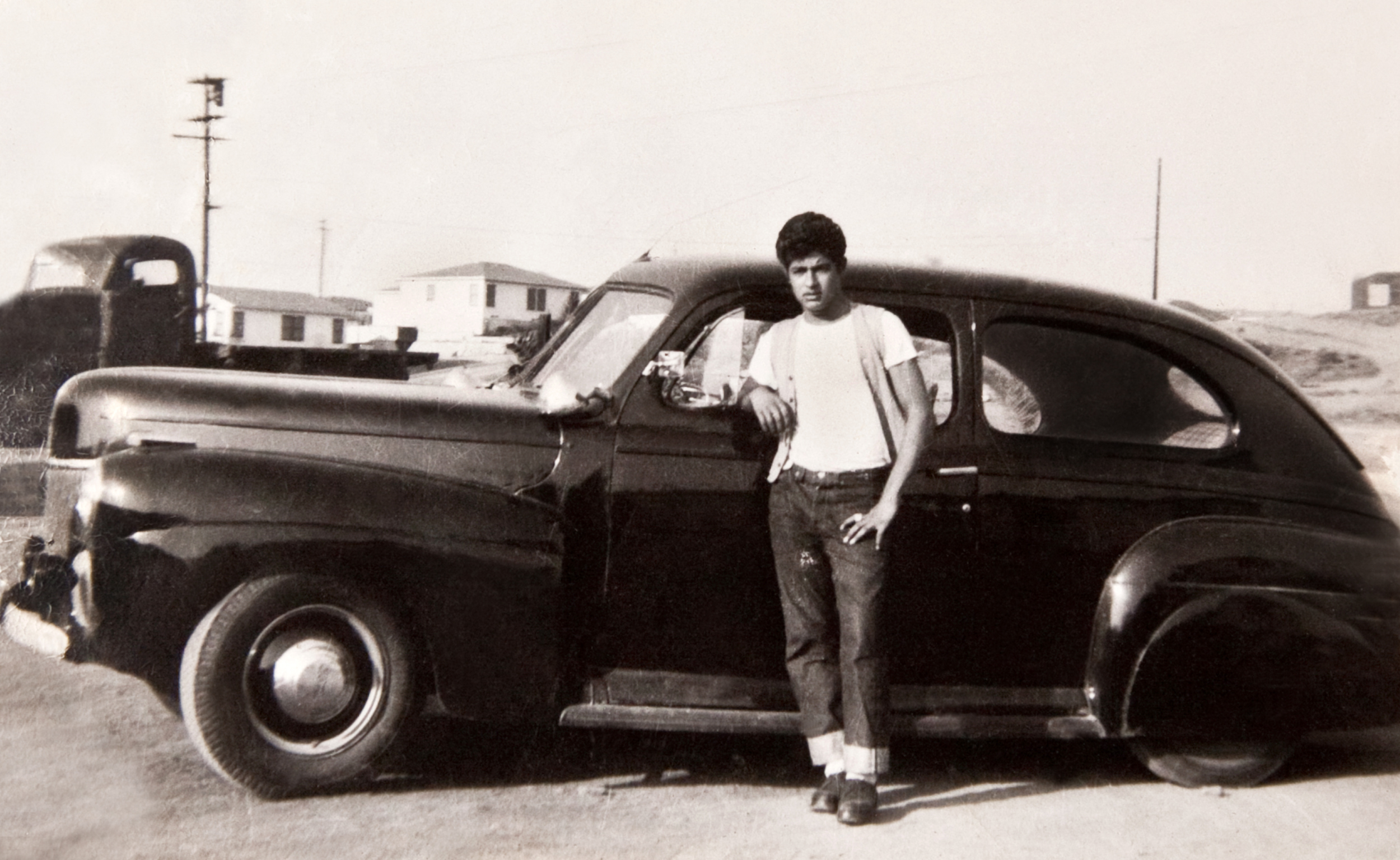

But despite the ongoing popularity of lowriding, the unique Mexican-American experience that gave birth to this subculture is often misunderstood. Arising after WWII, when car leisure activities like hot rodding, drag races, and demolition derbies began to flourish, lowriding gained a foothold amongst the barrio youth of Southern California. Participating in car culture was a way for this new generation to affirm their place in American culture, but it was also way to assert their bicultural identity. At that time, young Mexican-American veterans were returning from the war to find that, despite their sacrifices, Chicanos were still treated as second-class citizens in the US. In many ways, lowriding arose from the community’s need to be acknowledged; whereas hot rods were all about speed racing, lowriding was about cruising slowly down the boulevard – bajito y suavecito – in order to be seen.

Today, decades of negative media depictions have burdened the lowriding community with the stigma of gangbanging, violence and poverty. But a deeper look at history reveals it as a vibrant cultural expression centered on strong family and community values.

In order to celebrate this history, we’re looking back at a few influential people in lowriding history – some of them world-famous and others more under the radar – who helped put this culture on the map.

Ron Aguirre

According to Denise Sandoval, Professor of Chicana and Chicano Studies at California State University, Northridge, a Chicano man named Ron Aguirre put the first hydraulic system in a ‘56 convertible. The hydraulic parts were surplus parts from World War II fighter planes, and thanks to Aguirre’s work, they allowed the car to be lowered and raised with the flip of a switch. As Sandoval writes, “The surplus was soon a valuable asset to the low riders since they could ride as low as they wanted on the boulevard and if they saw the police, with a flip of a switch they were ‘street legal.’”

Jesse Valadez

The former president of The Imperials, one of the most distinguished car clubs in the world, Jesse Valadez was also the designer of The Gypsy Rose, which has been dubbed “the most influential custom car ever built.” As history tells it, in 1960 Valadez was inspired by the burlesque singer Gypsy Rose Lee to create the iconic pink lowrider using a Chevy Impala. Today, it is in its third iteration and in 2015 the car drew thousands of fans to an exhibition in East L.A.

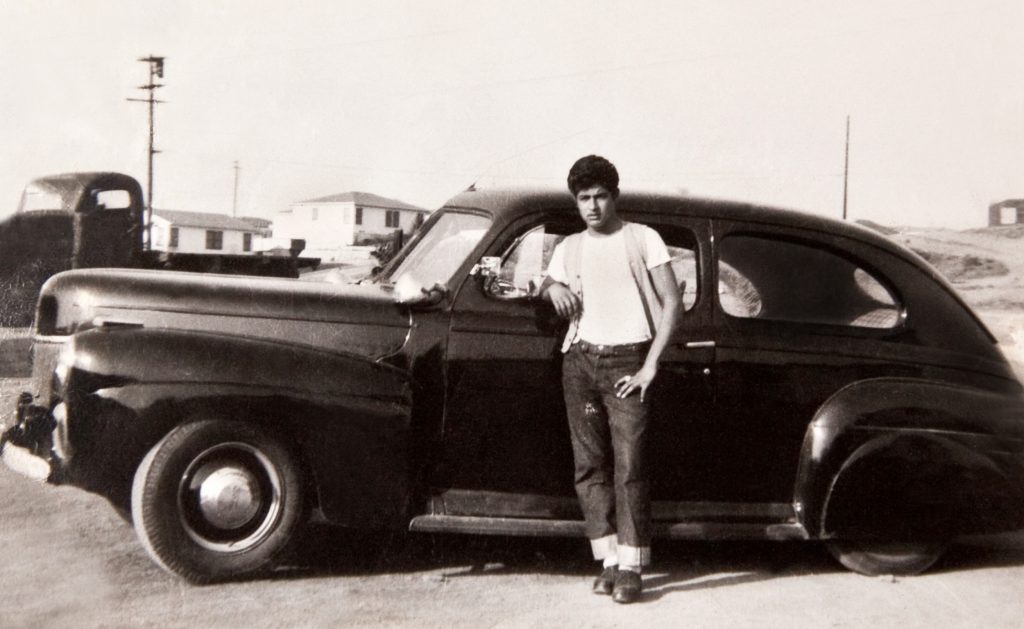

George Barris

George Barris and his brother Sam became one of the early faces of the lowriding community after developing one of the first businesses to customize lowriders for sale. At the time, they offered paint schemes and accessories you couldn’t find anywhere else. Building a lucrative career, the Barris business soon caught Hollywood’s eye. George would go on to introduce lowriders into films like High School Confidential and most notably, created the iconic 1966 Batmobile for the Batman television series.

Fernando Ruelas of Dukes car club

Fernando Ruelas, former President of the Dukes car club, helped usher a new era of community activism into the lowriding scene in the late 70s. According to scholar Denise Sandoval, the Dukes were an integral part of creating the West Coast Association of Lowriders in 1978, a group whose mission was to get car clubs to give back to the Chicano community. The association began a car show tradition called “Christmas Toys for Kids” which continues to this day, and the Dukes also regularly organized car shows to benefit the community – from Cesar Chavez and the United Farmworkers to Mecha to local prisons.

Larry Gonzalez, Sonny Madrid, and David Nuñez

In 1977, this trio of San Jose State students created one of lowriding’s most iconic publications: Lowrider Magazine. Seeking to present a voice for the Bay Area’s Chicano community, the publication soon became a bible of sorts for the lowriding scene. Its covers depicted tricked out cars and women wearing bikinis, but the pages within revealed a layered Chicano community, covering stories of community activism, police abuse, and the media’s misrepresentation of Mexican-Americans, among other things.

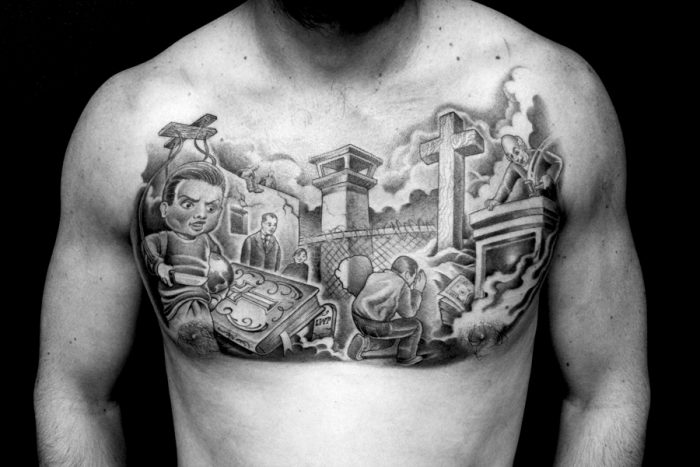

Teen Angel

Started in 1981 by enigmatic artist David Holland (also known as Teen Angel), the Teen Angels zine became known as the “voice of the Varrio,” the only publication at the time that featured the artwork, poems, dedications, photographs, and essays of Chicanos, particularly those who were gang-affiliated or in prison. Until the mid-2000s, when production of Teen Angels ceased, the magazine maintained a loyal, underground following among Chicanos who could finally see themselves reflected in print. For Teen Angel, it was important to show the value of cholos, gangsters, and prisoners, who unbeknownst to outsiders had developed a lifestyle that encompassed fashion, hair styles, lettering, graffiti, lowriding, tattoos, drawings, hand signs, and more. Teen Angel looked past negative stereotypes, and embraced what he saw as good and unique qualities of cholo lifestyle.

Chaz Bojórquez

Around the time that lowriding culture was flourishing, so was Chicano graffiti – and the form became intimately connected with the lowriding lifestyle. Known for its distinctive Old English lettering, the Chicano graffiti aesthetic has now become iconic – it informed an entire tattoo style, and is ubiquitous in today’s streetwear. World-famous graffiti artist Chaz Bojórquez is considered the godfather of this “cholo writing”, and has been active in the scene since the late 50s. He is widely revered as one of Los Angeles’ most prominent street art pioneers.

Mr. Cartoon

Mark Machado, better known as Mr. Cartoon, is one of LA’s best known masters of “Fineline Style” tattooing, an aesthetic that was developed in the California prison system and that became associated with cholo and lowriding culture. The legendary tattoo artist’s ink can be seen on everyone from Kobe Bryant to Justin Timberlake to Danny Trejo to Beyoncé, among many others – which may be why the LA Times once dubbed him “the Manolo Blahnik of tattoos.”

Estevan Oriol

After getting his start in the early 90s as tour manager for House of Pain and Cypress Hill, Estevan Oriol went on to become a celebrated photographer known for his work documenting Los Angeles’ Chicano street life, hip-hop culture, and the lowrider scene. His images helped spread awareness of this culture far and wide. Oriol also co-owns the iconic streetwear clothing line Joker Brand with good friend Mr. Cartoon.

Lowriders is set against the vibrant backdrop of East LA’s near-spiritual car culture and follows the story of Danny, a talented young street artist caught between the lowrider world inhabited by his old-school father and ex-con brother, and the adrenaline-fueled outlet that defines his self-expression.