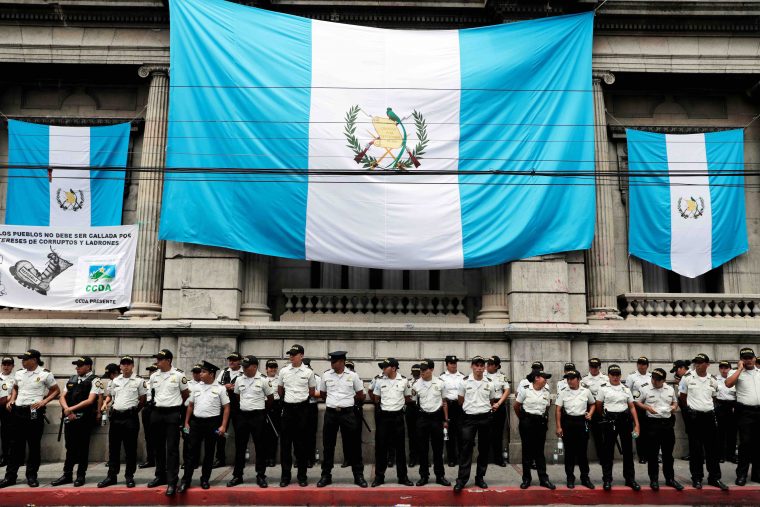

This year’s presidential election in Guatemala is crowded with mostly unknown candidates and few recognizable names – such as Sandra Torres, the runner-up in the 2015 election – who are either drowning in corruption allegations, have possible ties to drug traffickers, or are greedy political nobodies who have nothing new to offer. This campaign season has been plagued by arrests and legal proceedings against several presidential candidates, political manipulation and violence. At least two mayoral candidates in rural Guatemala were assassinated earlier this year, and at least one former presidential candidate received death threats.

To get a glimpse of the cluster that approximately eight million registered voters are walking into this Sunday: There are roughly 20 presidential hopefuls and at least 26 political parties fighting to control Guatemalan politics. All of the 158 seats in Congress, 338 mayoral spots, and 20 parliamentary seats for the Central American Parliament are also up for grabs on June 16.

As the era of President Jimmy Morales, who can only serve a single four-year term, comes to an end, and with a general conservative shift throughout Latin America, it’s important to keep an eye on Guatemala. Here’s what you should know about Sunday’s elections.

1

The Long List of Candidates

There are more than a dozen choices for Guatemalans come Sunday.

- Roberto Arzú. Arzú is a businessman. His father was Guatemala’s president from 1996 to 2000 and the former mayor of Guatemala City. He’s running with José Antonio Farias for the conservative PAN-Podemos party.

- Freddy Cabrera. He served as the Presidente del Colegio de Abogados. His vice president is Ricardo Sagastume. They’re part of the centrist TODOS party.

- Thelma Cabrera. She’s an Indigenous leader, whose running with Neftalí López. They represent Movimiento Para la Liberación de los Pueblos (MLP).

- Pablo Ceto. He’s a former member of Congress and diputado del Parlacen for Guatemala. His running mate is Blanca Estela Colop Alvarado. They’re part of the leftist Unidad Revolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca (URNG-MAIZ) party.

- José Luis Chea Urruela. He ran for president in 1995, and more recently, served as the Ministro de Cultura y Deportes. Along with vice presidential pick Mario Guillermo González Flores, they represent the left-leaning Productividad y Trabajo (PPT) party.

- Pablo Duarte Sáenz de Tejada. He’s a former member of congress, who is running with Roberto Villeda. He’s part of the far-right Partido Unionista (PU).

- Julio Héctor Estrada Domínguez. Estrada served as the Ministro de Finanzas Públicas from 2016 to 2018. His running mate is Yara Argueta. They’re part of the right-leaning Compromiso, Renovación y Orden (CREO).

- Isaac Farchi Sultán. Farchi is a businessman. He’s running with Ricardo Flores Asturias under center-right Visión con Valores (VIVA) party.

- Estuardo Galdámez. He’s been a diputado del Congreso since 2012. His vice presidential pick is Betty Marroquín Silva. They represent the right-leaning Frente de Convergencia Nacional (FCN), which is Jimmy Morales’ party.

- Aníbal García. He served as the secretario general of the leftist party Movimiento Nueva República (MNR) and he ran for president in 2015. He’s running with Carlos Pérez for the left-wing LIBRE party.

- Alejandro Giammattei. Serving as a leader for ultraconservative Vamos por una Guatemala Diferente (Vamos), Giammattei has run for president several times. He’s running with Guillermo Castillo.

- Manfredo Marroquín. He’s the founder of Acción Ciudadana. He’s running with Oscar Adolfo Morales for center-left Encuentro por Guatemala (EG).

- Benito Morales. He formerly ran for Congress, and now he’s running for the highest office, alongside Claudia Mariana Valiente. They represent the leftist Convergencia party.

- Edmond Mulet. He’s the former president of Congress. His running mate is Jorge Pérez. They’re running under the right-wing Humanista party.

- Amílcar Rivera Estévez. Rivera served as the mayor of Mixco. He’s running with Erico Can Saquic for the right-wing Victoria party.

- Danilo Roca Barillas. The former presidential candidate has chosen Manuel Martínez as his running mate. They’re part of the right-wing, anti-socialist Avanza party.

- Sandra Torres. The former first lady and presidential candidate is running with Carlos Raúl Morales for the Unidad Nacional de la Esperanza (UNE).

- Luis Velásquez Quiroa. Velásquez is the former minister of economy. He, along with running mate Arturo Soto, represent the Unidos party.

- Manuel Villacorta. He’s an academic. His vice president is Izabel Hernández Estrada. They represent Movimiento político Winaq.

2

Important Dates

The first round of elections will take place on Sunday, June 16. If no candidate receives 50% of the vote, then a run-off with the two leading candidates will take place on August 11.

3

The Issues

Most presidential and congressional candidates have been running on platforms of false promises to end poverty and improve education. They also vow to protect the “traditional family,” aka, infringing on the rights of the LGBTQ community. Also, what would political campaigns be in conservative Guatemala without condemning legal and safe access to abortions?

Perhaps the issue of most importance to politicians and the public is the future of the UN-backed anti-corruption agency, la Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en Guatemala, known as CICIG. The commission is staffed by both Guatemalan and international investigators, and has led charges against at least 700 businessmen, members of Congress, mayors, drug traffickers, and government ministers in Guatemala. Current President Jimmy Morales, who himself has been investigated by CICIG on corruption allegations, announced in January that his administration was cutting ties with the commission and expelling CICIG’s former commissioner, Iván Velásquez, from the country. Velásquez is originally from Colombia.

In the beginning of the election cycle, 70% of Guatemalans supported CICIG’s mission. Only eight political parties, including the new and fresh Movimiento Semilla and the more left-leaning Movimiento para la Liberación de los Pueblos, absolutely support the presence of CICIG in Guatemala. 15 other parties said they would definitely abolish the commission.

4

Banned Candidates

A former attorney general and a leader in the anti-corruption movement, Thelma Aldana, who was the presidential nominee for Movimiento Semilla, worked side-by-side with CICIG in hundreds of investigations against politicians and members of the Guatemalan elite. Aldana was one of the top presidential candidates until she was banned from the race in March when a warrant for her arrest was issued in Guatemala. She was accused of alleged illegal hiring, embezzlement, lying, and tax fraud – allegations she has strongly denied. Aldana challenged the decision to bar her from the presidential race, but ultimately Guatemala’s Constitutional Court reaffirmed her expulsion in May.

In April, Aldana tweeted, “It is a privilege to be persecuted by the corrupt, but it is a greater privilege to have good Guatemalans on my side. Truth is on our side. We are very close to seeing them fall. We’ll take to the streets but this time to celebrate a new Guatemala.” She hasn’t returned to the country since March. Aldana said during an interview with CNN en Español that she was also the target of death threats.

Another top choice for the presidency – Zury Ríos, the daughter of ex-military, genocidal dictator Efraín Ríos Montt – was also expelled from the race. She ran with the far-right party of Valor, and was kicked out of the race because the Guatemalan Constitution bans family members of coup leaders from running for president. She took her fight all the way up to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, but it denied her claim to be reinstated in the race. Ríos previously ran in 2015.

5

The Rise of Sandra Torres

The barring of Aldana and Ríos (two candidates who were total political opposites) may have paved the way for Sandra Torres of the Unidad Nacional de la Esperanza (UNE). While there are no clear front-runners yet, Torres, who landed in second place in the past presidential election, presently leads the polls with about 23% support. The possibility of a Torres presidency is, well, scary. There are serious accusations about her campaign being funded by drug traffickers, according to reports by CICIG.

Torres is this year’s presidential candidate with the most political experience in Guatemala. In the past 20 years, she’s participated in five presidential campaigns, some fighting for herself, and the rest helping her ex-husband, Álvaro Colom, become the president of Guatemala. Colom governed from 2008 to 2012. In 2009, Colom and Torres were tied to the murder of Guatemalan lawyer Rodrigo Rosenberg, who accused the pair of ordering his murder in a 17-minute YouTube video that was published after his funeral. CICIG later found that Rosenberg planned his own murder. This is a perfect example of the twilight zone that is Guatemala’s politics.

Torres’ party, UNE, defines itself as social-democratic and social-Christian, but in Guatemala these political labels oftentimes mean nothing. It comes down to greed and corruption no matter where you lean politically. With UNE, for instance, many of the candidates for Congress have allyships with other disturbing politicians, while others have been red-flagged by CICIG. According to the independent online newspaper Nómada, UNE is the party with the most strength this election. It has the highest number of candidates in both the municipal and congressional elections.

6

The Rest of the Top 3

Two other candidates trail Torres in the presidential race, including PAN-Podemos’ Roberto Arzú, the son of deceased Guatemala City mayor Álvaro Arzú. Roberto places third in the polls. Alejandro Giammattei, the former director of Guatemala’s penitentiary system, is in second place in the presidential polls. He’s running with the political party Vamos, and is also a common name in corruption allegations and other disturbing acts, including accusations of orchestrating the killings of a group of inmates in 2006. Giammattei, a conservative who does not support the anti-corruption commission CICIG, has run for president for the past 20 years, according to Nómada.

7

Other Races

The mayor elections in Guatemala City are one of the most important for residents of the capital. Roberto Arzú’s father, Álvaro, who was president of Guatemala from 1996 to 2000, had a monopoly over Guatemala City’s municipal government. Álvaro was elected mayor for six consecutive terms. He died of a heart attack playing golf in 2018. Arzú was a prominent member of the white Guatemalan elite.

Roberto, his son, is milking his father’s popularity, without the support of his own family or the political party of his late dad and brother, Álvaro Enrique Arzú Escobar. Arzú Escobar is a member of Congress running for re-election, with the extremely conservative Unionistas.

Like almost every political entity in Guatemala, the municipality, often referred to as MUNI, has been involved in corruption scandals. Most recently, the director of the MUNI’s music school, Bruno Campo, was accused of sexual harassment by several women. It’s very likely that Ricardo Quiñónez of the Unionista party will be formally elected mayor of Guatemala City. Currently, he leads the polls with 38.5% of support. Quiñónez took over the mayor’s office when Arzú died. He was also Arzú’s pupil.

As far as the congressional races, at least 150 candidates for Congress face criminal accusations or injunctions. Aldana’s political party, Movimiento Semilla, is running for several seats in Congress. Perhaps the most exciting candidate within that party is Lucrecia Hernández Mack, the daughter of renowned anthropologist Myrna Mack, who was murdered in 1990 by a US-backed death squad for her research and vivid criticism of the Guatemalan government’s violence against Indigenous people during the brutal 36-year civil war. Hernández Mack, and many of Movimiento Semilla candidates, advocate for Indigenous, women’s and LGBTQ+ rights, and are mostly progressive.

8

Thelma Cabrera and the Indigenous Movement

Another exciting candidate is Thelma Cabrera, the presidential nominee with Movimiento para la Liberación de los Pueblos (MLP), the first political party entirely organized by Indigenous communities.

Cabrera, a Mam woman and a leader for 26 years of the Campesinx Development Committee (Comité de Desarrollo Campesino, Codeca), is running on a platform of anti-imperialism, anti-racism, anti-sexism, and inclusion of Indigenous voices, who have been long ignored in political decisions. Among Cabrera’s main proposals are to declare Guatemala a plurinational state, fight for the human rights of Indigenous communities, protect the environment, and nationalize the country’s natural resources. The party’s slogan is, Elijo Dignidad. Critics say she’s too left and are angered by her reported support of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega.

Polls don’t even place Cabrera in the top three choices for president. But this hasn’t diminished the fire within MLP and its thousands of supporters throughout Guatemala. On June 8, MLP closed its campaign trail with a demonstration in Guatemala City. Hundreds of people filled the Plaza de la Constitución, the setting of countless protests, holding MLP flags and cheering for Cabrera, who hopes to become Guatemala’s first Indigenous female president. LGBTQ+ flags were also seen in the crowd, another sign of the inclusivity that fuels MLP’s movement.

“We have been governed by businessmen, military men, academics and, most recently, by a comedian,” Cabrera said to the crowd, referencing current President Morales. “We bring the fight from within the social movements in our territories…It is urgent to create a plurinational state to replace a failed state, a putrid state. We have to build a new state through the participation of the Mayan people, [Garinagu], Xincas and mestizos.”

9

What Guatemalans Need

Guatemala is dying for leaders who will invest in our country’s people, who will step up to the US and Mexican empires when Central Americans are being used as bargaining chips to negotiate economic agreements, who will respond with indignation when news arises that yet another Indigenous child and asylum seekers from Guatemala have been killed in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody, who will support anti-corruption movements, and who truly wants to see Guatemala bloom. But as Álvaro Montenegro, a prominent Guatemalan journalist, wrote in a New York Times column, a better future for Guatemala rests on the shoulders of el pueblo.