The Mess is a new column from journalist Richard Villegas, who has been reporting on new, exciting sounds flourishing in the Latin American underground for nearly a decade. As the host of the Songmess Podcast, his travels have intersected with fresh sounds, scene legends, ancestral traditions, and the socio-political contexts that influence your favorite artists. The Mess is about new trends and problematic faves whilst asking hard questions and shaking the table.

We’re going there. We’re talking about it. Even if things get a little messy.

It’s been almost a year since we kicked off this contentious little adventure called The Mess. In our maiden voyage, I raged about the problematic evolution of Pride and the many hypocrisies and contradictions plaguing the rainbow. It was exhausting. Now, as we saunter through another Pride season filled with right-wing antagonism, hilariously tone-deaf ad campaigns, and color-coded pop monoliths from Kenia Os and Charli XCX, I’m still in a fighting mood but with a different vibe. So, instead of vigorously shaking my fist toward the heavens because of Pride disillusionment, this year, I’m choosing to celebrate camp and the legacy of humor that has been our greatest tool when facing and dismantling hate. Look to the histories, and you’ll find limp-wristed sissies, butch maidens, and androgynous night crawlers scattered throughout pop culture, remembered more for their wit and magnetic personalities than gender rebellions.

Explaining camp is tricky since it’s an intangible sensibility coded into those of us who were “Born This Way.” We’re not exactly X-Men, but camp is like gay braille; not everyone can read it. More than an art form, camp is about perception. It’s finding humor in unnecessary extravagance or poor execution and discreetly whispering to yourself, “Werk.” A recent such example would be Jojo Siwa’s cringy viral turn, which miraculously achieved both. But camp is also camouflage – a defense mechanism for individuals too innately loud to go unnoticed, empowering us to redefine the narrative from “other” as an alienating quality into something unique and fun. In Spain, camp appeal elevated La Veneno from precarious sex work to celebrity wild card and trans godliness while paving a path from obscurity to mainstream acclaim for artsy nightclub weirdos like Alaska and Pedro Almodóvar.

Latine folk are intimately familiar with camp, even if we don’t always call it that. It’s the omnipresence of música de plancha and melodramatic divas like Amanda Miguel, Ana Gabriel, Daniela Romo, and Pimpinela’s Lucía Galán. It’s our obsession with bad telenovela acting and Thalia’s unhinged social media presence. It’s riding home after a 12-hour shift in a neon-lit bus blasting cumbia sonidera. It’s a video of Juan Gabriel dressed in head-to-toe sequin saved in your homophobic dad’s YouTube favorites or your abuelita’s bedroom mantel crowded by saints and virgins with more elaborate glam than a Drag Race contestant. You’ll learn quickly that kitsch and camp are cheeky sisters, though one pertains to aesthetics while the other is about warped intent.

“Watching Iris Chacon sing Raffaella Carrà’s ‘Caliente Caliente’ on her weekly TV show made me maricón,” says Eduardo Alegría, Puerto Rico’s first out rockstar and a cornerstone behind bands Superaquello and Alegría Rampante. “It’s a local cliché, yes. But that Chaconic legacy, in combination with teenage escapades to see Almodóvar films in adult cinemas, informed much of my work and goes hand in hand with my goth and art-pop influences. They make a lovely combination.”

Alegría began storming stages in the late ’90s, clad in outlandish costumes and heavy makeup, and met with his fair share of jeering audiences and flying beer bottles. But like most queers, he turned rejection into fuel, allying himself with the island’s dynamic theater community and fellow Boricua art provocateurs Macha Colón (“Todo En Su Sitio”) and Fofé Abreu (“Jirafa”). In fact, the Caribbean is abundant in camp — just consider the gothic ensembles of Dominican merengue vampire Toño Rosario and the towering Patti Labelle-esque wigs worn by Celia Cruz later in life. Speaking of Celia… Drag!

It should come as no surprise that drag is a foundation of camp, though here, gender performance and satire are weaponized to challenge stifling social conformity. Chile’s Hija de Perra was a fiercely political agent of chaos up until her death in 2014, while the chart-topping success of hyper-glamorous goddesses Pabllo Vittar and Gloria Groove has cemented drag into everyday Brazilian consciousness. Emerging in 1970s Mexico, Francis‘ lush cabaret reviews made her a trailblazer for drag on stage and film. And in the Dominican Republic, flamboyant television personality Raudy Torres introduced the curvaceous character of Roba la Gallina, now a national staple of carnival. Even RuPaul – before mutating into a global drag kaiju – spent the ’80s and ’90s preaching unabashed gayety on primetime television, award shows, and Congress. Safe spaces will always be vital for the LGBTQ+ community, but there’s a special respect reserved for those who unapologetically parade our exuberance in the status quo’s face.

“I think for something to be perceived as camp instead of just bizarre, a certain degree of naivete is necessary,” reflects Argentina’s Ceretti, the singer and visual artist whose debut album Todos Los Hombres Son Iguales arrived last month drenched in synthpop and technicolor saturation. “There’s melancholy for a time that isn’t our own. A lot of my influences, like Lio and Cicciolina, are derided as talentless because of people’s prejudices and expectations of how an artist should look or sound.”

“I enjoy frivolity, irony, and shamelessness,” adds singer and producer Matt Montero, co-founder of the label La Banda del V.I.P, alongside Ceretti, where they’ve collaborated with a fleet of local eccentrics including Violeta Castillo, Pielcitta, Ibiza Pareo, and Keity Moon. “That’s why I love Miranda!, who I’d say are the biggest exponents of camp in Argentine music. Other benchmarks include Dani Umpi [from Uruguay] and [Chile’s] Sofía Oportot, especially in her work with Lulu Jam.”

Camp is also camouflage – a defense mechanism for individuals too innately loud to go unnoticed, empowering us to redefine the narrative from “other” as an alienating quality into something unique and fun.

As I explained before, camp is like gay aurora borealis, and not everyone is equipped to see it. This is good. In a world where local news anchors parrot “yass queen” and “slay” like hackneyed season’s greetings, it’s evident straight people haven’t cracked the code of camp and thus can’t appropriate or exploit – at least more than they already do – our silly little Pig Latin. It’s part of why Nathy Peluso’s caffeinated productions make her come off as the cheer captain of Team Too Much, or whenever you see Harry Styles in some ill-conceived gender-bending outfit that looks like he was Punk’d by his One Direction bandmates.

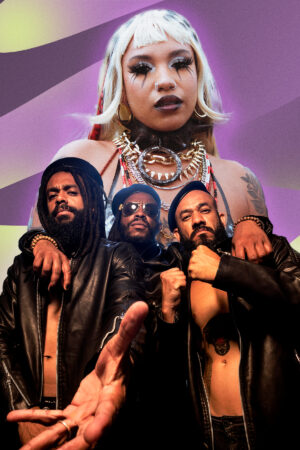

Camp is more often accidental than fabricated, and therein lies the joy of it all. It’s unpredictable, spontaneous magic sprinkled with glitter. I could go on forever, gushing over the fabulous ostentatiousness of La Tigresa del Oriente and Fefita La Grande, mythologizing trans actress La Bogue’s groundbreaking television career, or underscoring seminal texts by irreverent authors Pedro Lemebel and Copi. But I find that synthpop muscle daddy, Electrochongo, sums up the playful spirit of camp perfectly, hitting the stage in barely-there wrestling singlets to sing in the most dulcet of tones: “Música de putos, para gente linda.”