First-of-its-Kind Report Sheds Light on Grim Outcomes for Deported Salvadorans

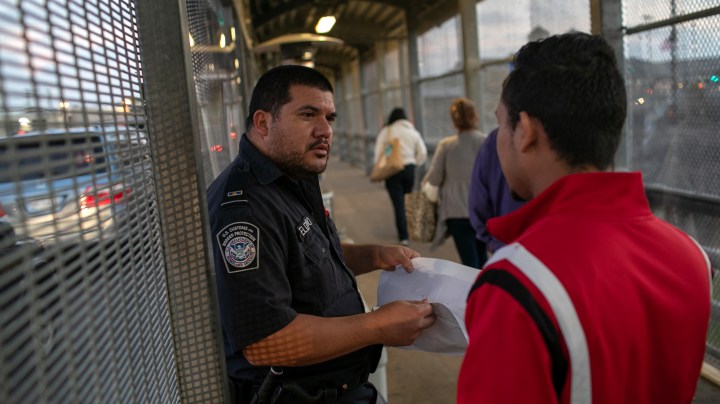

A U.S. Customs and Border Protection officer checks immigration documents as a Honduran asylum seeker arrives to the international bridge from Mexico to the United States on December 09, 2019 next to the border town of Matamoros, Mexico. Photo by John Moore/Getty Images

A new report by Human Rights Watch looks into the many harmful effects deportation has on Salvadorans. It found that thousands go missing, dozens are subjected to sexual or otherwise physical violence and at least 138 people have been killed since 2013 after deportation from the United States. The preliminary report is the first of its kind and covers a wide-lens scope of the situation from background information on why many consider the U.S. their last and only resort to the circumstances of leaving home and coming back again.

“No government, UN agency, or nongovernmental organization has systematically monitored what happens to deported persons once back in El Salvador. This report begins to fill that gap,” reads the report, which acknowledges potential gaps in the study. “Our research suggests that the number of those killed is likely greater.”

Deported women are particularly vulnerable targets. 67% of women in El Salvador are subjected to violence in some shape or form in their lifetime. The country has one of the highest rates of femicide in the world, according to Global Americans.

For Angelina N. it was abuse and harassment by two men – the father of her daughter and a male gang member – that pushed her to leave El Salvador. Unfortunately, she was deported back to El Salvador in 2014 – the same year she tried to cross the border – and the gang member, Mateo O., continued to threaten her.

“[He] came inside and forced me to have sex with him for the first time,” she said, according to the report. “He took out his gun.… I was so scared that I obeyed … when he left, I started crying. I didn’t say anything at the time or even file a complaint to the police. I thought it would be worse if I did because I thought someone from the police would likely tell [Mateo].… He told me he was going to kill my father and my daughter if I reported the [original and three subsequent] rapes, because I was ‘his woman.’ [He] hit me and told me that he wanted me all to himself.”

In addition to the very real fear of gangs, local authorities reportedly have a history of allegations of collaborating with criminals, further perpetuating the issue.

The number of Salvadoran asylum seekers in the U.S. increased by almost 1,000% from 2012 to 2017.

“It’s our responsibility to create the conditions where people don’t want to flee our country,” President Nayib Armando Bukele told CBS last summer. “We don’t have to be Switzerland. We just have to be more similar to Costa Rica or Panama and have our people wanting to stay there.”

However, the conditions that cause people to immigrate haven’t improved. Since being inaugurated as president of El Salvador, Bukele has mostly focused on aligning himself with President Donald Trump, who has worked to curb immigration from Central America to the United States.

To top off the study, HRW added a suggested range of paths forward for both the government of El Salvador to the powers that be in the United States. “End all unnecessary immigration detention,” it urged Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency (ICE).

“[The] U.S. is putting Salvadorans in harm’s way in circumstances where it knows or should know that harm is likely.”