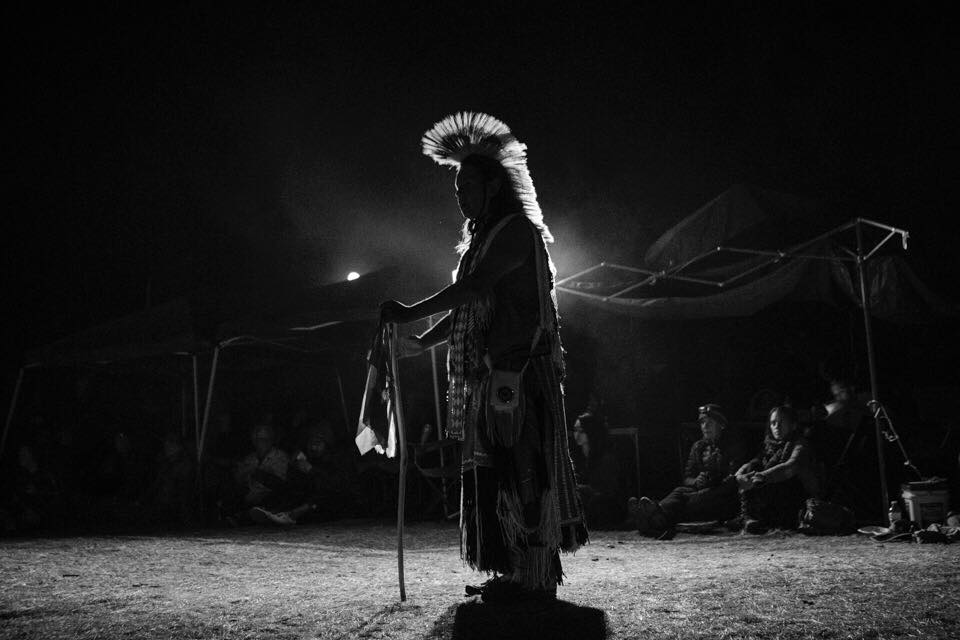

With an image depicting an indigenous water defender praying amidst a blizzard, Mexica photographer Josué Rivas captured the ongoing struggle at Standing Rock. As a matter of fact, for months, Rivas has documented every facet of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s stark opposition to the 1,172-mile long pipeline that threatens the group’s sacred lands and sole water source. Rivas was there Sunday when the Army Corps of Engineers announced that the North Dakota Access Pipeline wouldn’t be built beneath the Missouri River. He was there weeks ago when law enforcement aimed water cannons at protesters in 26-degree weather. He’s witnessed the words Mni Waconi – water is life – become a rallying cry. And he’ll be there in the future when land defenders learn of the project’s ultimate fate.

He did, however, miss the beginning of this conflict. In late 2014, Energy Transfer Partners LP applied to build a pipeline capable of carrying 570,000 barrels of crude oil from North Dakota to Iowa. By January of this year, only one state hadn’t greenlit the project, according to USA Today. This changed by March when the Iowa Utilities Board unanimously backed the pipeline. However, the same day, the Environmental Protection Agency requested that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers – which oversees dams, canals, and other public works – once again assess the environmental impact of DAPL.

When April rolled around, 200 Native Americans began protesting. Because it would cross on sacred Standing Rock Sioux land, the group pressured the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for an environmental impact study. In July, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe sued the U.S. Army Corps of engineers, who propeled the pipeline project forward after approving the final land easements. At the tail end of the month, Energy Transfer Partners begin prep work at constructions sites.

Rivas arrived at the Oceti Sakowin camp in August. “I first came to Standing Rock because my uncle asked me to come and document the opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline,” he told PDN. “My uncle is a medicine man from the Standing Rock reservation, and he felt it was important to have indigenous photographers and filmmakers lead in getting the story out.”

Since then, the #NoDAPL movement has mushroomed. When he first arrived, he saw 1,000 protesters, but eventually something like 10,000 people showed up to the camp. Native communities throughout the world have traveled to North Dakota to stand in solidarity with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. More than 280 tribes arrived on the plains of Dakota. Rivera has seen this superb display of camaraderie.

Because of his indigenous background, he has a thoughtful approach to his photography. “As an indigenous man, I feel the need to ask the spirits for guidance on how to approach the situation,” he said. “I always give thanks for everyday we get to have this many indigenous and allies in one place to pray and rebuild our strength as people. I’ve come to learn that there are many layers to this story, and I’ve been slowly peeling them. Whether I photograph around the camp or at the front lines, my approach is always to be respectful. I believe there is a lot of power in carrying a camera, so I use it wisely. My motto is to follow my light.”

For months, the mainstream media didn’t cover the #NoDAPL protests. But as the tribe’s fight gained traction, more journalists and photographers arrived, and the mood at the camp changed. At the beginning, Rivas took portraits of people. Eventually, activists became receptive to posing for photos. This forced Rivas to change his strategy. He started taking candid portraits, which he says put him “closer physically and spiritually as well.”

Because activists don’t always have control over how the media covers them, Rivas has found it important to stick it out in sub-freezing temperatures. As a result, he and his camera have captured the victories, the gruesome tactics employed to discourage protesters, and everything in between. As these water protectors settle in for the long fight ahead, Rivas’ photos will serve as a window into Standing Rock.

“I hope my photographs build a bridge between indigenous communities and the rest of the world,” he added. “We are at a time where unity and understanding for each other is crucial for survival. As we head to some of the darkest time in history, I was my documentation of indigenous resistance to be seen as a new chapter of our people. We are the sons and daughters of the survivors of colonization. We have the capacity and skills to tell our stories in a cohesive and unique way. Traditionally, our ancestors used oral history as the form of passing down the knowledge; now we are armed with technology, and there is nothing that can stop us. We are the seventh generation and we are rising.”

Check out a small collection of his striking images below:

To help Rivas continue his work, donate to his GoFundMe page.