Arizona’s Mexican-American Studies Ban Was Racially Motivated, According to Federal Judge

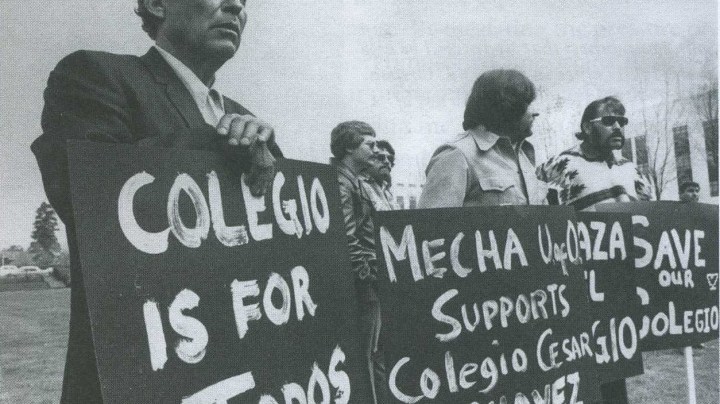

Creative Commons "Ayuda para colegio cesar chavez” by Movimiento is licensed under CC BY 3.0

After years of challenges to an Arizona law that effectively banned a Mexican-American Studies program, a federal judge ruled Tuesday that the state acted with discriminatory intent. In 2010, the Arizona legislature banned the Tucson Unified School District’s Mexican-American Studies program through House Bill 2281, according to the Tucson Weekly. HB 2281 made it illegal to teach classes that “promote the overthrow of the United States government,” “promote resentment toward a race or class of people,” “are designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group,” or “advocate ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils.”

U.S. District Judge A. Wallace Tashima ruled Tuesday that as the Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State of Arizona, Diane Douglas acted unconstitutionally by violating the students’ First and Fourteenth Amendment rights and several state statutes, including penalizing TUSD with a 10 percent state funding cut if the program continued.

In 2013, Judge Tashima stated that the part of HB 2281 that banning schools from creating courses for students of different ethnicities was illegal. Agreeing with his ruling, the Ninth Circuit Court sent the trial back down, so that a lower court could decide if HB 2271 came was racially motivated. The new trial took place in July.

In his decision, Tashima essentially judicially ethered former education leaders Tom Horne and John Huppenthal – who helped pass HB 2281. He saw through their flimsy justifications and called out their racial animus. “Additional evidence shows that defendants were pursuing these discriminatory ends in order to make political gains,” he wrote in the decision. “Horne and Huppenthal repeatedly pointed to their efforts against the MAS program in their respective 2011 political campaigns, including in speeches and radio advertisements. The issue was a political boon to the candidates.”

The decision laid bare just how far Horne and Huppenthal went to stop a program that taught historically underrepresented students about their own culture. Horne asked Representative Steve Montenegro, a Salvadoran-born immigrant, to support and manage the bill because as a Latino man his words would have more credence. Huppenthal rejected audits that found the program didn’t violate HB 2281, the law they wrote to specifically target MAS. They refused to observe the classes, though they said the classes taught students to hate others. Judge Tashima particularly eviscerated Huppenthal for making inflammatory comments in anonymity.

“Rather, they argued that Huppenthal’s public statements, which were facially neutral as to race, are more probative of his true intent,” the judge wrote, speaking specifically about the defense’s claim that “those private comments don’t reflect the public reason for taking action against TUSD’s MAS program.” “The Court is unpersuaded. The blog comments are more revealing of Huppenthal’s state-of-mind than his public statements because the guise of anonymity provided Huppenthal with a seeming safe-harbor to speakplainly. Huppenthal’s use of pseudonyms also shows consciousness of guilt. Had Huppenthal, a public official speaking in a public forum on a public issue, felt that his inflammatory statements were appropriate, he would not have hidden his identity.”

As for Horne, he admitted that he didn’t take aim at the Asian-American studies program because others told him the program “was academically an excellent program.” Even though others said similar things about the MAS program, Huppenthal and Horne refused to accept it as fact.

To this day, Huppenthal remains apprehensive that schools will “crank up all that stuff of teaching students that Caucasians are oppressors of Hispanics,” according to the Associated Press. This is a critique opposers have brought up time and again.

In 1968, San Francisco State University students known as the Third World Liberation Front began striking in an effort to push their university to initiate an ethnic studies program. The Third World Liberation Front succeeded, with ethnic studies eventually spreading across the country. But even with all the gains achieved in the last five decades, ethnic studies still face an uphill battle. Lawmakers have outright banned the studies because some believe they promote reverse racism and welcome leftist ideology in schools.

Yet, a Stanford University study released in 2016 found that ethnic studies benefit students. They miss fewer days at school, they get better grades, and even graduate at higher rates. This is especially true for Latino and male students. During the trial, the plaintiff’s expert Nolan Cabrera, a professor at the University of Arizona, found the TUSD program had the same kind of positive effects. TUSD students outperformed their peers in several ways.

“There is an empirically demonstrated, significant, and positive relationship between taking MAS classes and increased academic achievement – measured by increased high school graduation rates and increased AIMS tests passing rates – for all students who took the courses, but in particular for Mexican-American students in TUSD.”

The case isn’t quite over yet, as Judge Tashima will at a later date consider arguments from both sides as to the appropriate remedy. TUSD – which began the Mexican-American Studies program in 1998 – has not yet stated if it will revive the program.