In 1916, as war raged in the city of Aguascalientes, eleven-year-old Anita Brenner and her family got into a car and sped towards the train station. They had escaped Mexico before, but this time it was for good: Anita’s father had sold all of their belongings, including the furniture, to pay for the train ticket.

The family settled in San Antonio, except Anita, who grew up feeling out of place. San Antonio was her first encounter with practicing Jews, but they were nothing like the kings and queens that she had read about. She soon became aware of the profound differences between American Jews, and herself. As a Mexican-born American Jew, she was in a murky area: shunned as a Mexican by the American Jews, and discriminated against, as a Jew, by many American gentiles.

During her first year at the University of Texas, things got so bad that she couldn’t find appropriate student housing because of her Jewish identity. She finally made up her mind, and, much to her father’s disapproval, decided to return to the country that had been recently ravaged by the Mexican Revolution.

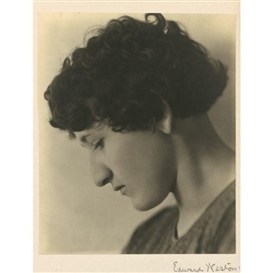

MUSEO NACIONAL DE ARTE, INBA

When she arrived in Mexico City in 1923, she found herself in the midst of a group of intellectuals and artists who have since become myths in Mexican history. In cafes and parties with Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and José Clemente Orozco she found her true calling as a bridge-builder, and established the basis of an international reputation that would follow her throughout her life.

As a journalist, an anthropologist, a cultural promoter and a traveler, Anita helped position the cultural movement called the Mexican Renaissance in the United States. Her hybrid identity allowed her to crisscross national boundaries, earning an important role as a type of cultural diplomat.

Her influence is still relevant. This September, the Skirball Center in Los Angeles will inaugurate the exhibition “Another Promised Land: Anita Brenner’s Mexico.” The show, featuring works by Diego Rivera, José Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Frida Kahlo, Mathias Goeritz and dozen more artists, attests to her impact.

Anita’s father, Isidore Brenner, was an American-nationalized entrepreneur from Latvia who traveled on bicycle across the US before settling in the Mexican state of Aguascalientes at the end of the 19th century. Porfirio Diaz, the President of Mexico at that time, promoted foreign investment across the country and turned Aguascalientes into the headquarters of American companies like the Smelting Company, owned by the Guggenheim brothers.

At first, Isidore worked as a waiter in the city, but he eventually scaled up. Over the years he established his own business, bought a big terrain in which he built a stable and planted fruit trees, established a Rotary Club and became a prominent public figure in town.

Despite the rapid industrialization of the country, many indigenous communities resented Diaz’s economic policies: most suffered under an oppressive land-owning scheme that excluded them from the profits. This created an unstable, explosive, social situation with anger against the foreign landowners accumulating.

When Anita, born in 1905, was five-years-old, her indigenous caretaker, Nana Serpia, pointed to the Halley comet and said it was a bad omen. She was right: that same year, a revolution to overthrow Diaz saw the light.

Keeping American investors’ interests in mind, the US intervened in favor of Diaz, and portrayed the revolutionaries – and Mexico – as a chaotic country that was falling apart. The invasive actions by the US sparked strong anti-American sentiments in Mexico: American flags were burned, consulates and American businesses attacked, and white-skinned foreigners were subject to harassment. Fearing for their lives as American-born property-owners, the Brenner family fled the country. On the train ride to the border, they passed as Germans by carrying a German flag.

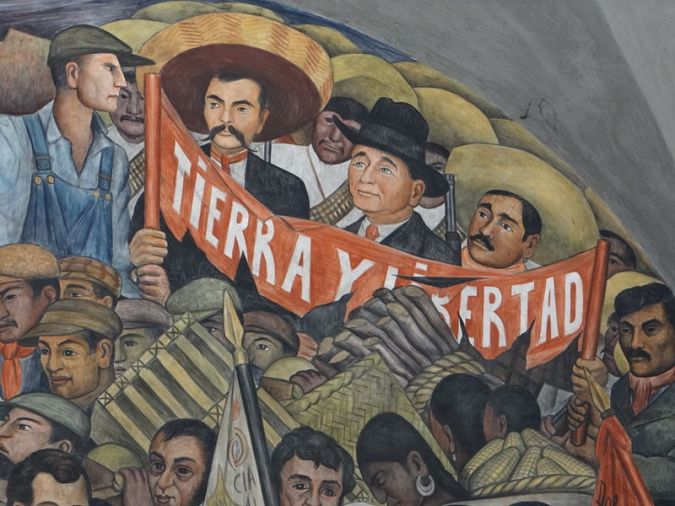

When 18 year-old Anita came back, Mexico was healing from the wounds of war and going through an incredibly creative phase. The Mexican Revolution, despite the horrible violence, had brought changes in the national narrative and a favorable evaluation of Mexico’s indigenous roots. There was a profound questioning of the Eurocentric narrative brought on by the Conquest, and a belief that the Revolution was meant to serve the underdogs.

Brenner was convinced that art had a major role to play in the self-fashioning of this new Mexico.

Anita soaked it all up. She was convinced that art had a major role to play in the self-fashioning of this new Mexico. Driven by this belief, she became friends with American liberal journalists and writers who were covering the social transformation, like John Dos Passos, as well as forming relationships with the like-minded-muralists Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

Her previous experience with the Jewish community of San Antonio had shaped her understanding of herself and the role of Jews in Mexico. She became conscious of how Mexico was portrayed negatively in the American media, and read stories published in the United States about the unfavorable situation for Jews south of the border. Anita, who played an active role welcoming new immigrant Jews into the port of Veracruz, was a fervent defender of her birth country: her first journalism pieces in The Nation and Jewish Telegraphic Agency were explicitly written to paint a positive picture of Mexico as a safe-haven for Jews.

These articles were the beginning of a lifelong quest to promote Mexican culture to an American audience. Anita, ever the migrant, moved to New York in 1925 and published, in English, her most famous book to this date, “Idols behind the Altars,” an eclectic view of Mexico’s indigenous traditions and contemporary artists. The book, which positioned the work of Rivera and Orozco as a continuation of Mexican popular culture, was an instant hit: she received praise letters from Spanish writer Miguel de Unamuno and British writer Richard Hughes. She was only 24 years old.

Despite her early fame, her intellectual production never waned. In 1929, under the tutorship of Frank Boaz, she graduated with a Ph.D. in Anthropology from Columbia University and won a Guggenheim fellowship, which she used as a honeymoon fund to travel to Europe and the Mexican state of Guerrero. She got involved in liberal circles and, as a journalist for The New York Times, was active in defending those who had been jailed during the Spanish Civil War.

She interviewed Trotsky for The Nation in 1933 and a couple of years after, when he had fled to Norway, she contacted Diego Rivera and told him that getting Trotsky out of Europe was a matter of life or death. Rivera, in turn, lobbied for Trotsky with Mexican President Lazaro Cardenas, who granted him asylum. Anita helped organize Trotsky’s acquittal trail in Mexico, in which famed philosopher John Dewey also participated. At the same time, she grew increasingly concerned about anti-Semitic attacks in Mexico City: as fascism raged in Europe, she wrote about groups who were organizing mass violence against immigrants.

Overall, she wrote more than 400 articles for different publications and published dozens of books, including The Wind that Swept Mexico, the first account of the Mexican Revolution in English. She was, above all a connector. Her parties and gatherings were legendary, and she was personally responsible for organizing the shows of many of her artist friends across the border.

Ten years after she moved back to Mexico, in 1955, she established the magazine “Mexico This Month,” which quickly turned into a Who’s Who of emerging artists, and featured names like Pedro Friedberg and Mathias Goeritz. In the sixties, she returned to her family’s plot of land in Aguascalientes and started growing all types of fruits and vegetables. She died in a car accident, on her way to her ranch.

According to her daughter, locals in the area often approach her talking about sightings of Anita Brenner’s ghost. She appears as a blonde woman, floating over her plot of land, and tells children to plant trees in her honor. “I tell them that they should treat me right, or my mother would come back in revenge. They don’t find it funny.”

With increasing xenophobia against Mexican and Latino immigrants in the wake of Trump, and the need to establish bridges between the United States and Mexico, Brenner’s life seems more relevant than ever. Los Angeles, with a sizable Jewish community and the biggest Mexican population outside of Mexico City, is a right setting to commemorate Brenner’s legacy. Particularly important, says Laura Mart, co-curator of the exhibition at Skirball, is expanding the idea of Mexico as a place of immigration.

Despite the important, lifelong role that Anita played in building bridges between countries, she never ceased to be a stranger in her land. When the Mexican government awarded her the Aztec Eagle, the highest honor given to a foreigner, Brenner declined it because she had been born in Mexico. This life-long conflict is summarized in the line of a poem that she wrote in her early twenties: “Daughter of two countries, citizen of none.”