If you ask Ariel “El Kumán” López, he’d tell you the only way to achieve greatness is by knocking people down, especially if your right hand packs dynamite and your main goal in life is to become boxing’s next Gran Campeón Mexicano.

He chose boxing as a career because he was sure his fists had the power to open doors that books may not have for him. El Kumán’s believed this since eighth grade when he began skipping school to spend his days at Gleason’s Gym, where his parents enrolled him up to curb his restless and tenacious spirit.

Some nine years later, the 23-year-old professional boxer out of Brighton Beach, New York, looks beyond bragging about his undefeated record (12-0, 7KO) or his 2014 Golden Gloves championship. The soft-spoken López instead admits his toughest fight is away from the ring.

As a beneficiary of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, the about 27 months of Donald Trump’s presidency have brought a wide range of emotions and affected his life and boxing career.

“Unlike school, boxing is something I can do well. What I do in the ring is my job,” López tells me. “If DACA goes away, if I get deported, I will no longer have the means to support my family and pursue my boxing career. I think of that, y está cabrón.”

López, who took his boxing name from his dad’s former life as a luchador in his native Puebla, is the kind of fighter who always pushes forward, unafraid of the blow he’ll endure as he aims to land his powerful right hand on his opponent. That aggressive determination caught the eye of Martín González, an experienced boxing trainer at Gleason’s Gym.

“It was hard not to notice him. I would see him training here, and boy was he brave,” González says. “He approached me. We began working together and that is when his talent started exploding. In a few months, we were winning championships, medals, and trophies.”

Prior to turning pro, López made a name for himself as a powerful puncher in the amateur boxing scene. Fighting in the 123 lb. weight division, he won the New York Daily News Golden Gloves in 2014 and came close to winning again in 2016, but the judges saw him lose to Dominique Crowder in the championship bout.

Unfortunately, his success wasn’t enough to allow him to compete in the Golden Gloves nationals. USA Boxing, the entity regulating amateurs in this discipline, began requiring proof of U.S. citizenship from all fighters competing in national tournaments in 2010.

A slew of undocumented fighters, such as welterweight Boubacar Sylla and super flyweight Alexis Zazueta, found out the hard way how serious USA Boxing is about the citizenship requirement. Knowing what he was up against, López and his team saw this as a sign: It was time to turn pro.

His immigration status had made his boxing career more challenging up to this point. “When I picked up boxing, traveling to competitions was almost always out of the question,” he says.

In 2012, that slightly changed once the Obama administration began rolling out DACA as a palliative for a broken immigration system that currently has around 11 million immigrants living in the U.S. with no legal status.

But DACA didn’t magically solve all his problems. On a visit to Puerto Rico for an amateur tournament, López was stopped for questioning and he couldn’t offer up his social security card. He had forgotten it.

“I was waiting in line wearing my Virgen de Guadalupe sweater and it read Mexico, too,” he recalls. “They came straight to me and asked me for my visa. They held me there and my friend stayed with me. We were there for hours. We lost our flight. I called my lawyer and they eventually let me go.”

El Kumán – who grew up in a household that prayed daily to la Virgen de Guadalupe – turned to la Virgencita that day. Despite the protection and comfort she’s offered him throughout his life, she couldn’t keep the president’s policies from affecting the young boxer’s aspirations.

When Trump took office as 45th president of the United States, a 20-year-old López was barely eight months into his professional boxing career. The DACA work permit he had allowed him to earn enough to provide for his U.S.-born son, Ares, and pay his trainer.

As he climbed the boxing ladder, El Kumán picked up a few bouts deep in Trump country, something that made traveling riskier. At the onset of Trump’s presidency, the media began to report that DACA recipients and DREAMers had been detained and even deported. This meant, he had to take more precautions for his matches across the United States.

In February 2017, for example, he was set to fight Alan Beeman in Raleigh, North Carolina. But instead of flying in, he rented a car and drove the 500 miles. A month later, El Kumán and his trainer decided to fly from New York to Palm Bay, Florida. The anxious duo never stopped looking over their shoulders.

“Flying scared me the most,” he says. “I thought immigration could be waiting for me at the gate and I wondered, ‘What if I get deported? I wouldn’t be able to say goodbye to my relatives.'”

It’s not just at the airport that he feels like a target, it’s also inside the ring. When he walks into a venue, he doesn’t shy away from repping his Mexican heritage. One summer evening in 2017, López – a red sombrero crowning his head and a serape with the Mexican flag draping his wiry figure – marched to the ring as Chente Fernández’s rendition of “El Rey” blared from the arena loudspeakers. Some in the mostly white crowd began to chant, “Build the wall! Build the wall!” and “Go back to your country!” at him.

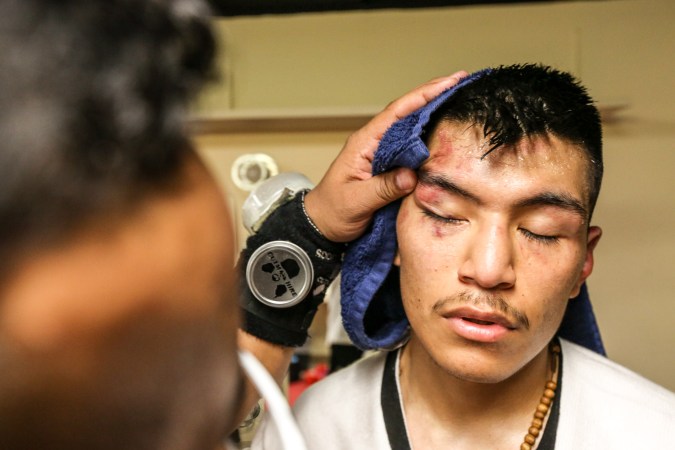

An unfazed López pranced toward the ring, his eyes fixed forward. Even in New York, a young immigrant kid grows up being called all kinds of slurs for not looking American enough. The fight at the Tropicana has been his most brutal outing to date. His bruised face and cut ear would not convince many he won the six-round affair in a split decision against a bigger and faster Charles Clarke. The narrow decision inflamed the volatile crowd and the rain of slurs resumed as López and his team made a quick exit.

As the future remains unclear for the estimated 690,000 young immigrants benefitting from DACA, López is working to change his status. In July 2017, he married Angélica Rojas, a U.S. citizen and his high school sweetheart. They have already started the process of getting him a marriage green card, but regularizing status after marrying a US citizen has proven difficult for him. In the meantime, he’s hopeful that a Trump presidency won’t extend into a second term.

But even with a possible change of leadership in 2020, El Kumán knows that xenophobia is pervasive in this country. “I have even seen Mexicans on his side and I don’t get it,” he says.

Still, this doesn’t stop him from celebrating his roots.

“I’m proud of representing Mexico,” he adds. “Mexicans are the toughest fighters out there. Everybody knows Mexicans works hard. When people see me fight I want them to say, ‘That fighter is Mexican.'”