I think often of the first line in Toni Morrison’s Sula, “In that place, where they tore the nightshade and blackberry patches from their roots to make room for the Medallion City Golf Course, there was once a neighborhood.” The book begins with an admission of loss, which is how many of us Brooklyn-raised folks preface conversations about gentrifying communities. “Things are a lot different now,” we say.

A year ago, the last Panamanian restaurant in Brooklyn closed. (At the time of its closing, it was the only Panamanian restaurant in Brooklyn.)

For 50 years, Kelso Bistro Bar & Restaurant served Crown Heights’ Caribbean community, creating a cultural hub for an often invisible Afro-Panamanian population. A small group at the intersection of both West Indian and Latinx identities, Afro-Panamanians in New York don’t typically enjoy the same kind of recognition as other groups with similar origins – such as Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, Jamaicans, or Haitians. While this lack of familiarity probably has more to do with population size than anything else, it seems that outside of the annual Panamanian Parade during fall, our city rarely remembers Panama.

On this one weekend in October, Panamanians from all over New York, the East Coast, and Panama itself converge on Franklin Avenue, glowing in traditional polleras, breaking it down to the drumline beat from Atlanta’s best bandas, or marching behind la comparsa, flags billowing in the air. But then November arrives, and for the next year, Panamanians experience little public visibility.

And, like so many other things in Brooklyn, the tactile evidence of Panamanians having been there keeps disappearing. That Kelso was the last restaurant of its kind speaks to this change. For me, its recent closure and the shifting landscape in which it happened, feel personal: In 1966, my great-aunt Julie opened Kelso, and although she sold the restaurant soon after I was born, its legacy was profoundly important within our family.

Like so many other things in Brooklyn, the tactile evidence of Panamanians having been there keeps disappearing.

On most Sundays while I was growing up, my parents, siblings, and I would head over from Fort Greene to Tía Julie’s for a late lunch. She, along with my grandmother and another aunt, lived in Tivoli Towers, the pair of concrete buildings over on Franklin and Crown that were so tall they became something like my True North, a way to reorient myself from anywhere in Central Brooklyn. On these Sundays, Tía Julie cooked a feast of Caribbean food – rice and peas, sweet plantains, oxtail, kingfish if we were celebrating something – and we’d wash it all down with Pepsi.

On other days, our grandmother would take my brothers and I downstairs with her to run errands: to the supermarket beside Medgar Evers College, to the corner store where she bought numbers for both the New York and Panamanian lottos, and sometimes to Golden Krust, where she’d treat us to a cheese danish or currant roll.

These moments were affirmations of a Panamanian heritage grounded specifically in Brooklyn, a borough with an expansive Afro-diasporic lineage. But years have passed since those afternoons, and Crown Heights has transformed. Franklin Avenue, for instance – once a landmark thoroughfare for longtime residents – is now a gathering place for recent college graduates and their older, yuppie counterparts. The new shops are familiar; so deliberate in their aesthetic and niche, they recall the storefronts that years ago arrived in Williamsburg. They become another tell that the neighborhood is going.

As it changes, I feel a combined urgency to mourn and document, as though the razing of old buildings will extend to public memory. It’s that sense of rapid encroachment commonly invoked in discussions about gentrification; before it’s gone, we explain.

Like many Panamanians, my family has lived in Brooklyn since the 1960s. Our people are double migrants – Black West Indians who came to Panama to work on the canal, and then just a generation later raised children who would leave home again. And we weren’t the only ones. In the 1960s, migration from the Caribbean and Latin America exploded, as economic and political conditions became less stable in some of our countries, and immigration policies in Britain tightened, leaving the US as the next option for West Indian migrants. By 1970, West Indians and Latin Americans together comprised nearly half of New York’s foreign-born population.

My family remembers arriving in a racially diverse but segregated Brooklyn, with boundaries drawn around specific blocks rather than whole neighborhoods. Crown Heights, for instance, was divided between Hasidic Jews and Black people from the Caribbean, Central America, or the South. My uncle tells stories about strategically plotting his way home from school as a teen, dodging certain blocks where white neighbors might harass him. This particular brand of segregation, coupled with the unfamiliar cold of winter, often made those first years in the US hardest. Plus, New York City had recently sunken into economic recession, prompting a mass exodus of white people, who relocated to the suburbs and took their wealth with them.

It’s a familiar story – disinvestment followed by disrepair. But that’s not the sum of what happened in Brooklyn. Instead, the residents who stayed and those recently arrived built vibrant communities together, learning their vecinos’ names, planting trees on sidewalks that had been empty before, opening up bodegas, hosting loud parties on weekend nights, marrying each other. In Crown Heights, my Tía Julie was one of those community-builders. She had long boasted a talent for cooking, and after she got lucky one weekend in 1965 betting on a horse race, she decided to open up a restaurant. She named it after the winning horse – Kelso.

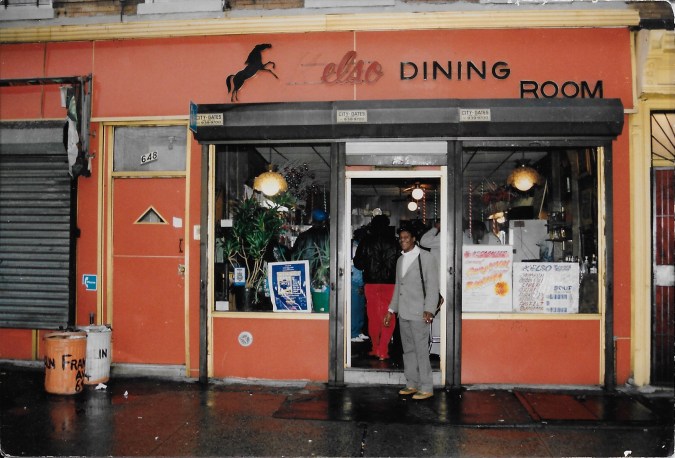

Housed on Franklin Avenue between St. Marks and Bergen, Kelso provided a space for Crown Heights’ Caribbeans to experience something like back home. Veronica Parker, a Panamanian immigrant who bought Kelso decades later, lived around the corner from the restaurant in its earlier years. In a conversation, she told me that Kelso had made her adjustment to New York much easier. “You’d see all your people [there],” she says.

This was a sort of golden age for New York Panamanians. Just a few years after Kelso’s opening came several other Panamanian businesses. A popular bar called Gold Coast, which was just a block away, encouraged an unofficial partnership with the restaurant. “People could go to Kelso for dinner, Gold Coast for drinks and music, and then, when it got late, back to Kelso to sit in the patio and play cards,” my father tells me.

The little community was important in other ways, too; local civil rights leaders, including Reverend Al Sharpton, would periodically come by to campaign, ask for donations, or field concerns from the patrons. One might call it an early example of the multiethnic organizing so many of us call for today.

Old pictures from this era look glamorous to me. In one, my Tía Julie stands outside Kelso in a red dress, her hands gracefully splayed against the glass. In another, women, friends of Tía Julie and my grandmother, gather around a table with half-full glasses of rum in front of them. My grandmother wears a mola stitched to the front of her dress, and dangles a cigarette in one hand. My Tía Julie is, as usual, in leopard print.

Aggressive privatization was chosen as the pathway to a new, thriving city.

Then, in the 1980s, some parts of New York City started to shift. These changes – like rising rents, or “renewal” policies that replaced small residential buildings with commercial developments – were scattered and at first mostly in Manhattan. But they were signs of a larger transformation: A New York in which aggressive privatization was chosen as the pathway to a new, thriving city.

Gloria Karamañites, who won Miss Panama in 1980, immigrated to the States in the early ’90s, and remembers that even then, Crown Heights was still the central nerve of the community. “If you wanted fritura, you had to go to Crown Heights. If you wanted to go to a bar, you had to go to Crown Heights,” she says. She lived in East Flatbush, but would head to Hector López bar or Walterio’s for a night out. Over the next decade, however, those businesses closed and the neighborhood began to radically change.

Panamanians, along with their other West Indian counterparts, started leaving Crown Heights. Although it wasn’t just displacement that sent people out; some were pulled by the promise of domestic work on Long Island, or opportunities for home ownership just outside the city. Many in the latter group could stitch together middle-class lives out in the suburbs. This mobility complicates my feelings of loss; can you still mourn people who have chosen to leave? Especially when so much of what hurts about gentrification is that it forces people to go – that it exposes the absence of mobility, of choice.

Still, there are many ways to be pushed out. Other folks in Crown Heights – including my own family – stayed and watched over years, how it began to slip a bit beyond their reach. For my grandmother, this slippage wasn’t measured in new white neighbors, but in the progressing, perhaps intentional, deterioration of her apartment building. Heat that wouldn’t come on until late in the winter even after complaints to the landlords; an elevator that was constantly broken, demanding that she walk up fourteen flights of stairs with groceries; roaches, no matter how many times she coated the kitchen counter with Lysol; and vague threats of rising rent.

“We tried to keep it going because of love of cooking and love of community.”

These individual household issues emerged in a larger context of change: Between 2000 and 2010, Crown Heights’ Black population dropped, while the white population swelled, increasing by 203 percent. Home value rose with the arrival of new white residents, tripling between 2000 and 2016. And Black businesses in New York City overall have not fared well through gentrification: In just five years, they declined by about 30 percent, far more than in other parts of the country.

Ms. Parker, Kelso’s most recent owner, finally decided to sell the restaurant when running it became unviable, in part due to cost of rent. “We tried to keep it going,” she tells me, “because of love of cooking and love of community.” But at some point, that wasn’t enough: Last October, Veronica celebrated the restaurant’s long life with Panamanian flags draped over the windows – a local Panamanian marching band playing on the sidewalk outside – and lots of food. When I spoke with her, she seemed at peace with Kelso’s closure, although she expressed some regret at the broader pattern of Caribbean business closures throughout Crown Heights. “We’re being pushed out,” she says.

So who will remember the small restaurants? The people who owned them? Or the regular customers, who each week asked for bacaláo and a side of patacones? To be clear, there are still Panamanians in Brooklyn – in Flatbush, Crown Heights, Canarsie, Bed-Stuy, Clinton Hill. Veronica runs Kelso as a mobile catering business now – and in fact, drew a crowd at the most recent Panamanian Day Parade. Just last year, Panamanian and Brooklynite Kalima DeSuze opened Café con Libros, a feminist bookstore on Rogers Avenue. But this particular community – the one that first brought tastes of Colón, San Miguelito, and Rio Abajo to Brooklyn, the one that claimed my family for more than 50 years – is now scattered across the East Coast. And opportunities to return to the old neighborhood are limited because of the cost of housing. Of course, my communal grieving is amplified by a personal one: Tía Julie and my grandmother have both passed, too.

In 2010, a local commission of Panamanians tried to co-name Franklin Avenue “Panama Way” in honor of the historical influence and demographic presence they’ve had in Crown Heights. The initial effort proved unsuccessful – a neighborhood association opposed it, plus the city had recently outlawed naming streets after countries – but the attempt tells us something about home. How it stretches across borders, how it remakes itself, how it disappears. And how we might honor it: in that place, there was once a neighborhood.