Editor’s Note, December 13, 2018: Since the publishing of this article, Esquivel has been accused of sexual and emotional abuse. Two collaborators on Border Town have since left. We have reached out to DC Vertigo and will update if and when we receive a response.

December 14, 2018: Remezcla has learned that DC sent retailers a cancellation notice. The notice to retailers states that issues No. 5 and No. 6 of Border Town will not be published and all previous issues will be made returnable.

Borders are imaginary boundaries that many modern politicians use to discern the humanity of a person. But many people knowledgeable with the current immigrant experience have asked themselves what exactly defines a border. In Eric Esquivel, Ramon Villalobos, and Tamra Bonvillain’s new comic, Border Town, the border is about more than just immigration status; it’s a horror story that looks at the borders between good and evil.

“It was not just about the physical border between US and Mexico; it’s about the borders we put up between each other. These fake ideologies, like I’m left and you’re right,” 31-year-old Esquivel tells me. “These fake borderlines that are man-made concepts and even things that we divide between like gender and stuff like that. It seems like a lot of folks are benefitting from drawing these imaginary lines between each other.”

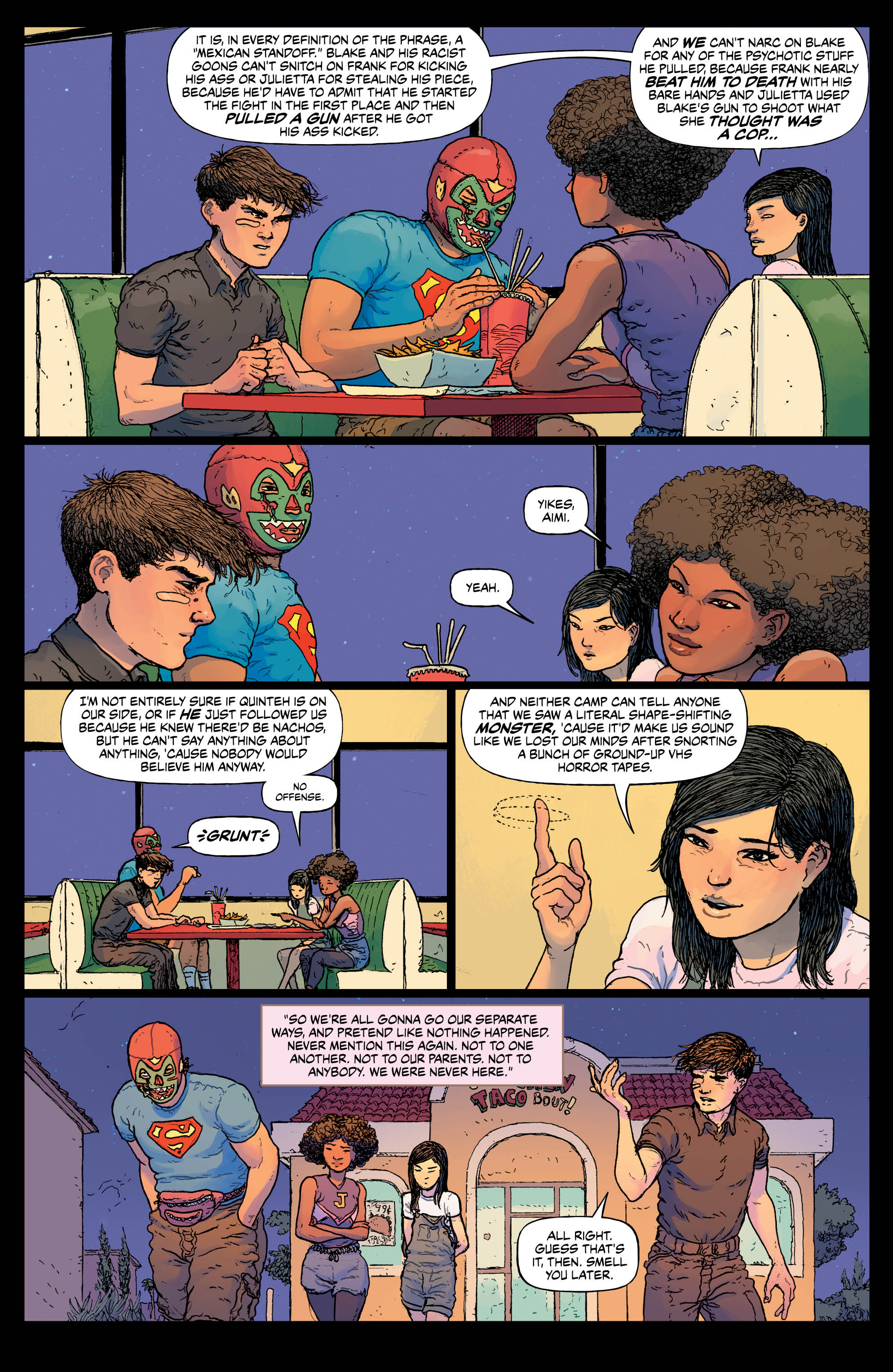

Border Town, which some have called the “Mexican-American Stranger Things,” has resonated so much that the first issue needed to be reprinted by DC Vertigo (a DC Comics imprint) in the last few years. The story centers on Frank – a half Irish, half-Mexican high schooler, who moves with his mom and step-dad to what feels like the mouth of hell (it’s actually Devil’s Fork, Arizona). On his first day, he sees Quinteh, a teenager who wears a lucha libre mask and towers over everyone else, wrestling with a vending machine, asking it to return his “pinche” quarter back.

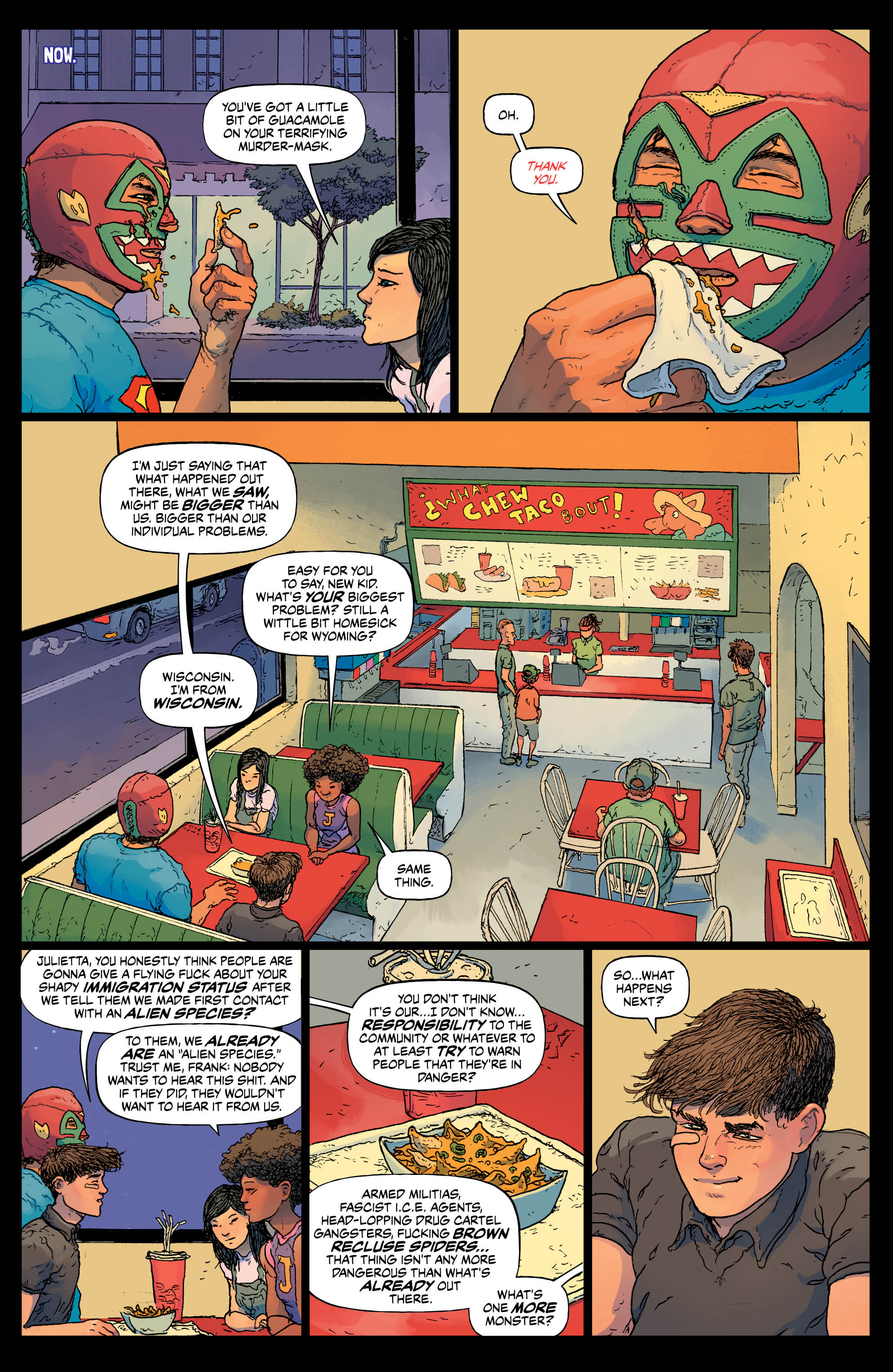

Because Frank is white, those at his new school don’t realize he’s also Mexican-American. Frank quickly learns of the racial tensions at the school. He could quietly go to school, not engage with the school’s politics and the white supremacists, and live a peaceful life. Instead, the story’s moral centers, Aimi and Julietta, approach him. They try to learn “what his deal is.” At the same time, Nazi skinhead Blake and Quinteh – people on complete sides of the spectrum – take a liking to him. They want to know where he stands. At this point, the reader sees one of the comic’s famous panels: Frank proudly proclaims he’s half-Mexican. Julietta responds by saying he’s not half anything; instead, he is Irish, Mexican, and American.

“There is a school that has that comic as part of their Chicano lit class.”

“Every day, I get a tweet from someone that says they were teary-eyed reading that panel. That’s what they wanted,” says Esquivel, who is Irish Mexican. “I have parents who’ve told me they gave it to their daughters and their sons to read. There is a school that has that comic as part of their Chicano lit class. That idea is such a rarely communicated idea, that I’m really proud that it’s in there, but initially I was terrified. This whole comic was basically so I could have that panel in there, so somebody else could read it and understand their place in the world.”

Although the title of the book evokes very specific imagery about immigration, it’s not exclusively about this issue. At its core, the book follows a horror story set at the border, and immigration forms one part – not the entire part – of people’s lives. It deals with both the US-Mexico border, as well as the one between our world and the universe of terrifying monsters.

Esquivel pulled from his own background and personal experiences growing up in Arizona. “I wanted to be one of the cool kids,” he adds. “I had the opportunity now as a writer, to sit down and create the book that I wanted when I was a kid. And the fact that it isn’t super after school special political, it’s an adventure story with monsters and it takes place in the American Southwest on the border, I think that’s what’s making it pop. People don’t want to be preached to, but they’ll read an exciting adventure story.”

After the introduction of the main characters, the book takes a twisted turn. Esquivel could have just written about the real horrors at the US-Mexico border, such as border militias carrying AR-43s and white supremacists. Instead, he tapped into the monsters our parents frightened us with – that is, El Chupacabras, La Llorona, El Cucuy, Mictlantecuhtli, El Silbón, Pichilingis, La Luz Mala, La Mano Peluda, La Siguanaba, La Lechuza, El Cadejo Negro, and Los Duendes.

The combination of Esquivel’s writing, Villalobos artwork, and Bonvillain vivid colors make the story pop. The story makes Arizona appear as though it’s stuck in a specific place and time. Every part of the artwork was deliberate. Because this was a Latinx-led story about Latinx kids, the entire team wanted to make sure they were true to themselves and strove to highlight overlooked and marginalized voices, particularly within our communities.

“When I started I had a notebook where I wrote down a visual reference for every character – what music they listened to, what kind of clothes they would wear,” Villalobos tells me. “Just from the identities that Eric gave me. For each character, I didn’t want there to be a Latinx stereotype.”

They took special consideration when creating the female characters, Julietta and Aimi. Traditionally, comic writers have faced problems writing complex, three-dimensional female characters. They tend to fall into some sort of trope, such as the damsel in distress.

“Feminism means equality, and this book is trying to represent that in a realistic light. And that includes the female characters, like Aimi, who is an Afro-Latina character, and Julieta, who is undocumented. And that’s an experience that I don’t ever see in media, any of those things really,” Esquivel explains, “In America, you are the darkest thing that you are – like Lupita Nyong’o, who grew up in Mexico and speaks Spanish. In the Marvel franchise, she is just Wakandan, she is just African, we see her as just black and not as an Afro-Latina, just like Zoe Saldana. She is in the Marvel Universe but she’s painted green. We’re allowed to be in it if we’re aliens or others but not from our own [community].

“I really wanted to have an Afro-Latina character front and center, who is proud of her identity. That’s why she gives the speech to Frank. I want people to know that she knows what she’s talking about, and I wanted it to be explained. And the fact that she’s Afro-Latina is important, and it gets glossed over way too much.”

“I really wanted to have an Afro-Latina character front and center, who is proud of her identity.”

And it’s not just Julieta’s identity that goes unacknowledged, it’s also true for Aimi, an Asian-Latinx character. “Aimi as an Asian-Latina gal is even less represented,” he says. “I have a lot of people in my life who are Asian-Latinx, and that’s not represented anywhere in media, and there is a lot of cultural crossover between Japan and Mexico.”

Stories about our communities don’t always get the platform they deserve, with decision makers saying they don’t sell well. However, as recent films (Black Panther and Crazy Rich Asians, for example) have shown, diversity is profitable. Border Town actually sold out in five days. But it wasn’t just positivity in the air, some who consider themselves gatekeepers of the comic world, spewed hatred at the book and the author.

“For this book, we had death threats,” Esquivel remembers. “When it was announced that I was going to appear in San Diego Comic-Con in a Vertigo panel, the tweets they were sending me were, ‘We’re not going to send ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement]; this time we’re sending exterminators.’”

Some stores didn’t even want to carry the book. “The thing that has hurt me the most is that there are a lot of people that tweet me and Facebook message [me] that don’t know me that [are] excited about the book, who go into their local store and sign up for a local subscription and try to order it, and the stores refused them,” Esquivel explains. “Before it was sold out they just didn’t want to order it because of the content, because of the characters. That kills me. I want to believe that all comic book readers are trying to be Batman and are virtuous cool people, but a lot of stores just didn’t want Mexicans in it and they didn’t set up a subscription book for them.”

After the comic dropped, however, everything changed. Not only did Border Town sell out, but it became Vertigo’s first comic to go into reprint in five years, following in the footsteps of Neil Gaiman’s Sandman Overture.

Esquivel, Villalobos, and Bonvillain do not have Gaiman’s fame or esteem, but what they have is a strong story, steeped in reality and Latin American mythology. It’s not only speaking to our community, but also people who aren’t Latinx, who are learning about our cultures and our monsters, which are just as terrifying and interesting as Eurocentric ones. Esquivel knows the monsters have staying power, and now that he’s made a splash in the comic world, he hopes to also change the face of TV and film to include more people who are on the margins.

“My goal as a writer is to be a job creator,” Esquivel adds. “I want to create characters that live on after me and I want to create properties that become adapted into TV shows and movies so that we get more Latinx actors and directors and writers and set dressers a job. I want there to be more colorful faces on things like DC’s TV app that they just debuted and the Justice League. I want to create a world where we’re part of the conversation. Because as long as I have been alive, we’ve loved their stuff. I have Batman tattoos, and it wasn’t till trying to work in the industry that I realized the things that I loved don’t always love me back and that killed me. So my career now for the rest of my life going forward is, I want things to be easier for the next young woman or man who wants to write and draw comics. I want it to be a given that we’re a part of this and a part of the conversation and that we create books that sell out. It’s not only British guys in trench coats that work at Vertigo.”