Since far-right politician Jair Bolsonaro was elected president in October 2018, Brazil has faced significant cultural changes – mostly by force. In addition to threatening the rights of women, people of color and LGBTQ communities, the president has also taken multiple measures to censor artwork that’s contrary to his ultra-conservative and fundamentalist views. Ironically, some of his biggest critics have been using culture and art to challenge him.

After effectively assuming power in January 2019, the Bolsonaro administration has sought to censor media that is pro-LGBTQ or includes messages in defense of diversity and inclusion. For instance, the president has imposed censorship against ANCINE, the national film promotion agency, as well an advertisement by Banco do Brasil for focusing on “diversity.”

His presence has also emboldened other far-right politicians to do the same. At the beginning of the year, Rio de Janeiro Gov. Wilson Witzel, who is ideologically aligned with Bolsonaro, canceled an exhibition and artistic performance that illustrated the torture present during Brazil’s period of military dictatorship. In September, Marcello Crivella, the mayor of the city of Rio de Janeiro, and evangelical fundamentalist pastor Marcelo Crivella ordered every copy of Avengers: The Children’s Crusade be taken off sale in the city because one of the pages included two male teenagers kissing. Last year, Crivella also closed a venue that was showing a play where a trans person was cast as Jesus Christ.

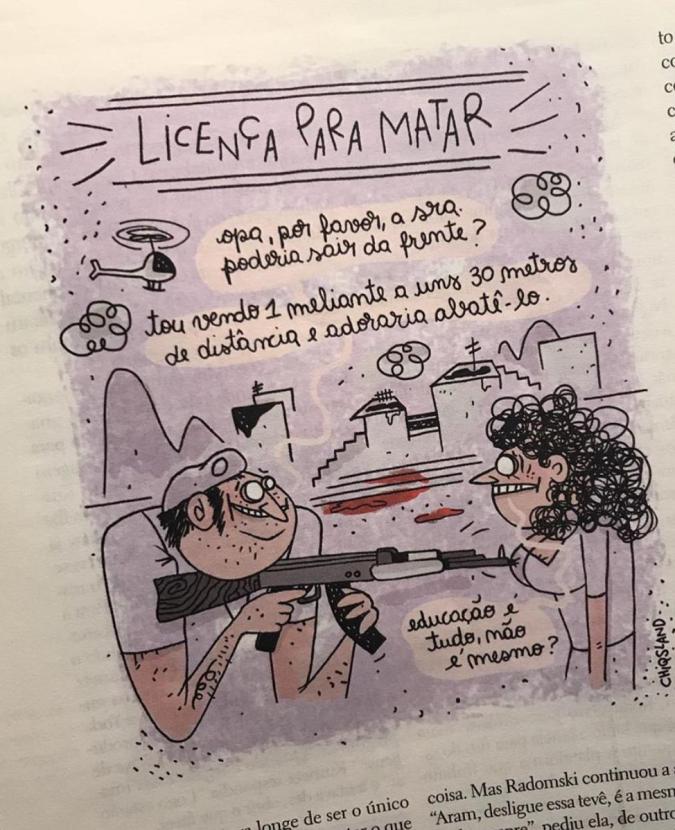

In the midst of this culture war, creatives have been turning to social media to use art and humor to push back. There is a growing number of cartoonists using social networks as instruments to criticize the government, its supporters and sometimes society as a whole.

“I didn’t even do much political cartooning before the Bolsonaro government, but I’ve always been critical of any government,” cartoon artist Adão Iturrusgarai tells Remezcla. “I never defended FHC, Lula and Dilma, but this government is hors concours. There is an urgent need to attack.”

“I didn’t even do much political cartooning before the Bolsonaro government.”

Adão is famous for his provocative cartoons, which carry strong sexual appeal and social criticism. Among his most famous characters are Rocky and Hudson, two gay cowboys who are a critique of performative and traditional masculinity, and Aline, a woman who symbolizes sexual liberation as she is always with her two boyfriends. Increasingly, his work has also taken aim at Bolsonaro, with many pieces comparing him to U.S. President Donald Trump.

“It’s easier to make humor during disastrous governments. Still, I prefer good governments,” Adão, who is currently based in Argentina and is releasing a book next month with his best political cartoons, says. “Humor has to be critical. You have to be against [someone]. It’s not humorous if you’re in favor.”

For Fabiane Langona, one of the few female cartoonists featured on the pages of the South American country’s major newspapers, it’s easy to poke fun at any government, but it becomes a critical tool of resistance under a harsh administration.

“The choice is whether the punchline will be softer or more direct and aggressive, [and] in certain matters a certain aggressiveness … ends up being a necessity,” she says.

Her cartoons usually deal with everyday life, often ironizing the habits of young people and also criticizing gender and social stereotypes — the latter evermore pressing under conservative political leadership that aims to reverse some of the advancement women have seen in the country.

While humorous cartoons are one way to challenge governments, Langona says it can also allow people who are impacted by repressive policies or are inundated with political news to “take a break.”

“People deserve a breather. They deserve a breath because it is practically impossible to think of anything other than the troupe of jerks that makes up Bolsonaro’s government,” she says.

But not all cartoonists are using comedy to question social issues and denounce governmental policies. Ricardo Coimbra, who has shared his cartoons on his blog “Life and Work of Myself” for the last 10 years, prefers for his art to be more “anarchic, uncontrollable, volatile.” For him, humor doesn’t hold the power needed to overthrow a government.

“The fact is that, as a cartoonist, the Bolsonaro government has meant to me a kind of obsolescence of humor,” he says. “There is no absurdity about this government that you can come up with that will overcome what it actually delivers.”

Coimbra is a social critic who doesn’t fear pointing his finger at conservatives, progressives or even himself. Even though political issues are recurrent in his work, he considers his art to be more social chronicles rather than political criticism.

“What interests me is people’s behavior, and, since politics is an omnipresent theme in people’s lives and behavior today, it ends up being omnipresent in my work as well,” he says.

“There is no absurdity about this government that you can come up with that will overcome what it actually delivers.”

While social media has allowed artists to challenge governments at a time when traditional, mainstream media is largely being censored, it doesn’t come without backlash. Online, these creatives open themselves up to condemnation and even violence. For example, popular YouTuber Felipe Neto often uses his platform for humor and entertainment, but under the Bolsonaro administration, he has increasingly been talking about politics on his Twitter account and sharing educational content about censorship and bigotry.

As a result, the YouTuber, who has more than 34 million subscribers, has received death threats. The remarks have been so severe that he asked his mother to leave the country for a while, fearing for her life.

Coimbra is among the many artists and cultural workers in Brazil challenging governments who has experienced threats because of the nature of his work. During the presidential election last year, the artist said he received death notes both online and at his home address. For him, these menacing warnings say more about the type of people who support governments like that of Bolsonaro than of his work.

“[This government] represents a real threat, even if it continues to hide behind a supposedly harmless image of popular humor against ‘political correctness,’” he says.