The 2016 election results were bleak. Instead of quietly awaiting the impending presidency, concerned citizens flocked to make donations to at-risk local and national causes. Although many nonprofits typically fare well during end-of-year fundraising campaigns, organizations like Planned Parenthood and ACLU saw extraordinary upticks in financial contributions. But not everyone was in a position to make financial contributions. Carlos, a queer comedian based in Portland, Oregon, found themselves with a lot of discomfort and time on their hands, but not a lot of money.

“I was in between jobs and freshly single. I didn’t really have the resources or money to respond or to do much of anything. I couldn’t donate to the ACLU, I couldn’t pay for people’s Lyfts to get out downtown or into downtown [for protests], and I couldn’t put any money where my mouth was,” recalls Carlos. “A lot people were hurting and I had an idea.”

Carlos the Rollerblader (as they’re best known in Portland) decided to put their love of talking to people to use with a free advice hotline. “It was supposed to be fun where I’d give drunk advice,” they explained. But after several days of heavy drinking, Carlos realized this was a bad idea.

“I think I got to four in a row before I realized I couldn’t do five,” they say. Rather than ditching the idea entirely, Carlos opted to consult a friend. “We were spit balling and that’s when it came: it’s just going to be advice.”

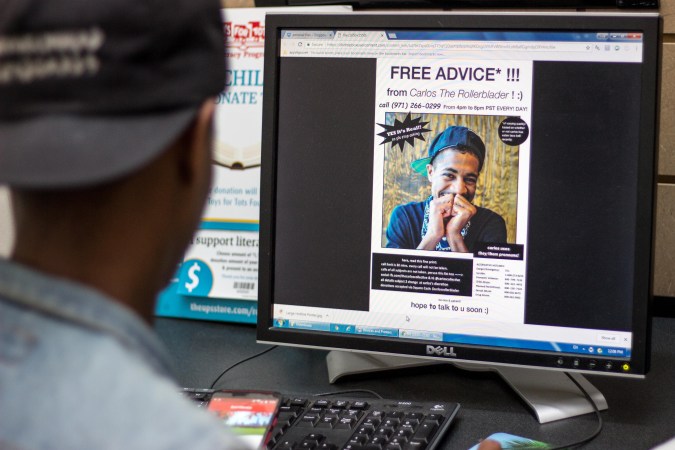

By February, Carlos was blading around town, slapping ads for the new hotline onto telephone poles and inside café windows. The first iteration of the ad featured an angelic, grinning Carlos with a heady mix of Arial and Comic Sans fonts and the words “FREE ADVICE*” written in all caps. The asterisk notation warned that the quality of advice would vary depending on how recently Carlos had ingested Taco Bell.

Shortly after putting the first run of posters up, Carlos wrote on Instagram, “I don’t really have a lot to give but the least I can do is listen, maybe make someone laugh… I just hope I can help someone thru a hard thing or let them know they’re not alone. Especially under Orange’s Administration.”

Days later, Carlos’ ads went locally viral. “There was a huge response. I got a call from a filmmaker [in Los Angeles] who wanted to make a profile on me within a week or two. Some free newspapers contacted me and wanted to do a write up,” says Carlos. “So many people called immediately and they didn’t know if it was real or not. A lot of them were just investigating. It was a really really crazy month.”

While confusing for some, Carlos explains that the playful nature and meme-esque aesthetics of the ads were intentional. “I decided to give it some subtext, so it was a little silly but a little serious. It was like, ‘If you have shitty roommates or roommates with shitty politics or your parents are on the wrong side of the fence or if you just need somebody to talk to because you feel alone in some capacity, please call me.’” Since Carlos isn’t a mental health professional, they wanted to differentiate their offerings and stress the casual tone. And for those in need of specialized assistance, newer versions of the poster include a detailed list of alternative emergency hotlines including ones for suicide, domestic violence, and sexual assault support.

Spending hours each day talking to strangers might sound daunting, but for Carlos the Rollerblader, the hotline has been a natural progression in a lifetime of practicing and exercising vulnerability. “Some would say that because I’m a Leo sun, Cancer moon, Scorpio rising, that it’s just a lot of emotions all of the time. I would say that yeah, that has to do with some of it, but I also had to do a lot of stuff on my own as a kid. I had to communicate in ways that others couldn’t. I had to speak for people. I had to represent things that other people weren’t able to. And so that just put me in a place where I had to sort of be collected on a consistent basis.”

As much as this collected demeanor stemmed from their responsibilities, it was also a reaction to the gendered treatment of emotionality. “[Emotional vulnerability] is a response to me watching men in my life and seeing how out of touch with their feelings they are. I grew up around mostly women—I was raised by women and I have seven sisters. I saw how the expectation is almost reversed; they have to be emotional and they’re expected to do emotional labor. So, unintentionally as a kid, I was always trying to offset that with the balance between my sisters and whoever else, or my dad and any of the women in my family. It’s always been a bridging the gap sort of having it together.”

The hotline has also inadvertently provided another avenue for gap bridging. “When white people call the hotline—and I always know when they’re white—I make sure that they know what’s happening like, ‘Hey, I’m Brown. We don’t have the same experiences, don’t assume anything, have empathy, etcetera.’ Sometimes when people call and they complain about things, I check them. I gotta be like, ‘You’re really privileged, you know?’ and they’re like ‘Yeah, maybe that’s…’ and then it starts a [conversation.] It’s never in an attacking or offensive way. It’s just something that has to happen when you’re being that vulnerable with a stranger. So, I don’t let people run all over me and then I can save my energy for people who really need it—people of color (POC) especially that call.”

In the years since relocating from Baltimore in 2013, Carlos has had the opportunity to flourish creatively and personally. Between running the hotline, hosting POC dating mixers, and doing stand-up comedy, “Moving to Portland has also really given me a lot perspective, believe it or not [through] meeting so many different kinds of people,” says Carlos. While black American cultural cornerstones like cookouts and gospel music marked their Maryland upbringing, Carlos says learning about the varying experiences of identity through people of color living in Portland gave space to rethink their relationship to the Dominican heritage on their mom’s side.

“I always felt guilty for not connecting to [my Dominican roots.] My name is Carlos Juan and I don’t speak any Spanish and I always felt guilty about it like it was my obligation, but I don’t feel so bad anymore… I have been discouraged most of my life, up until I moved to Portland, by Latinx people—especially because of how fucking racist they can be towards black people. So I haven’t really wanted to reach out to people [in the Latinx community] until I moved here. I realized that I don’t need to be so guarded and I can sense it a little bit better now when people are anti-black.”

While the hope is that queer and trans people of color (QTPOC) know their calls are a priority, Carlos says, “I don’t want anybody to feel hyper encouraged or discouraged from calling my hotline.” In moments when Carlos needs advice, they turn to their grandma, aunt, and best friend Jamal. Although nothing has drastically changed since the launch of the hotline, Carlos admits they’re surprised with how forthcoming others are. “People tell me a lot of their fucking business—people lay it down. And I keep it really safe and I’m privileged, I feel. When people trust you, it’s like a little gift.”

At the end of the day, Carlos wants to remind hotline callers and fans that they’re just a person whose moods ebb and flow (and who deserves Taco Bell sponsorship.) Beyond being available for your calls, Carlos wants to remind people, “Black lives matter. Pay women for their emotional labor. Call your mom.”

Editor’s Note: As a nonbinary individual, Carlos prefers the plural pronoun ‘they.’