Parents looking for playful ways to talk to their child about menstruation can find a gentle but wise compass in the new picture book Tribu de Mujeres. With warm-hearted illustrations, Ecuadorian academic and menstrual educator-turned-author Paulina Vásquez Quirola takes readers on a fantastical trip between awakened states and lucid dreams in a girl’s reconciliation with her changing body. Hopping from classroom scenes, where periods are shamed, to vibrant celebrations in mystical women’s circles, the book offers a tender critique and a colorful alternative to the cultural stigma that still predominates family circles and schools when it comes to periods.

“This book empowers girls.”

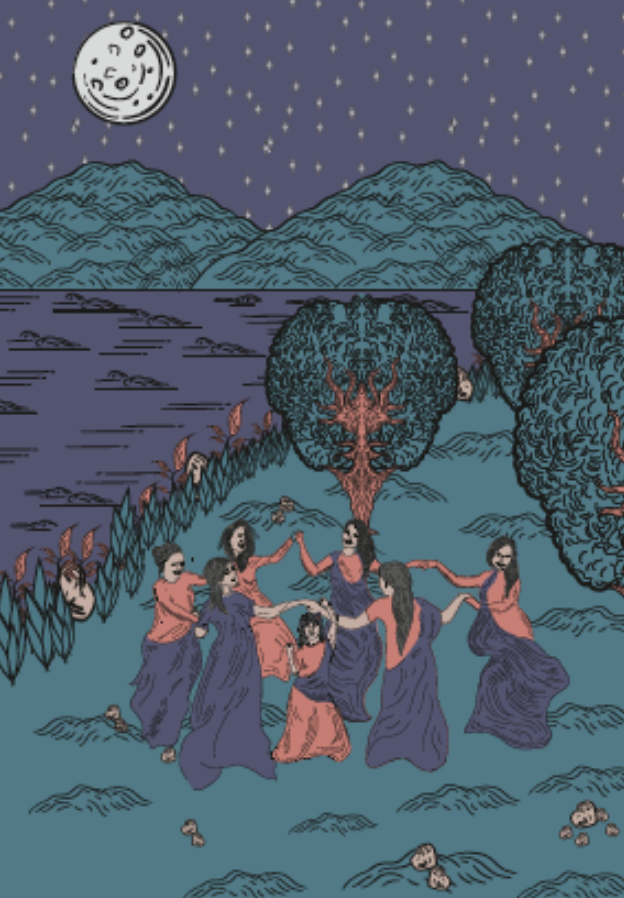

The loosely autobiographical picture book, wondrously illustrated by José Rafael Delgado, sees a hopeful future for the ancestral wisdom of the Andes transmitted by elderly women like its protagonist, Abuela Killa. When passed on from one generation to the next, young people learn that menstruation reveals the creative urge and cyclic nature of all living beings and life itself.

At a time when sex education in the U.S. and across Latin America still filters through the conservative principle of abstinence, despite high rates of teen pregnancies and sexual violence against minors, the book is refreshing and much needed.

Quirola, who is also the founder of Vientres Libres, a community that shares literature to help women and girls learn about their bodies shame-free, talks to Remezcla about the process behind her new book and everything we still need to learn and unlearn about menstruation and our cyclic being.

We have edited and condensed this interview for clarity.

Why did you want to write this book?

My personal experience was partly the inspiration to write the book itself. I rediscovered my body about six to seven years ago through an illness that I had. It was like, Wow, what’s going on with my uterus? What’s going on with my cycle? Women are so disconnected because they don’t teach us from an early age to befriend our cycles. That, I think, is what we need to do. We know we have a uterus and we know that menstruation happens, but we live it as something tiresome, as something exhausting. So it’s like, shit, it came! It’s time again! When is it over? Many of us have that negative view of our cycle.

I wanted to make a connection to my cycle, and I discovered the importance of understanding ourselves cyclically, of understanding ourselves as part of nature, as part of a whole. I think that is one of the big issues. Modernity and the system in which we live makes us disconnect from ourselves, from others in the sense of community and nature, the universe, from something much bigger. We believe we are islands, including this separation we have from our own bodies. As Abuela Killa tells the girl Tamia, she is part of nature, of a dance of nature.

I found the contrast between the school and the dream state fascinating. At school, the girl Tamia learns to be ashamed of her menstrual cycle. In the state of sleep, Tamia experiences a rite of passage in a beautiful red dress and flowers in her hair, celebrated, honored and welcomed by other women for having her first period. Can you tell us why you included this contrast?

There are cultures where menstruation is lived differently, so the body is undoubtedly perceived differently across societies and time periods. It is not the same to perceive the cycles and the body from an Andean culture than from a more westernized and urban culture, or from the Afro or Arab traditions. Each society constructs bodies socially.

“Women are so disconnected because they don’t teach us from an early age to befriend our cycles.”

In that sense, I mixed two temporalities to make a contrast visible. I had an interview with an Indigenous leader of the Amazon who said that some 20 to 30 years ago, rituals were still performed with girls who had their first menstruation. Rituals were done because they are rites that help people move from one stage to another, as the term implies. They are important on social and psychological levels because they prepare a person to accept a change in a more organic way and accompanied by community.

In the second temporality, we see Tamia in her school. It refers to our western, urban, mestizo context. Here, you see these processes are invisibilized. There is a discourse on sanitation of the bodies in general, where she learns odors and overflows must be suppressed. Basically, her cycles have to be silenced, made invisible, tamed and sanitized.

In the end, Tamia finds answers to her concerns in the ancestral wisdom through the messages that Abuella Killa sends her. I think these processes of loving and understanding our bodies, as well as accepting ourselves, are important.

Why are these ideas about menstruation, shameful vs. sacred, so different?

I believe, and in fact there is research that indicates, this is in part rooted in Judeo-Christianity. If you refer to religious texts, women are considered impure and even more when she is on her period, with messages that she has to get away from the community and is sometimes even forbidden to enter sacred temples.

But many Indigenous communities saw and see menstruation differently. Just look at our Valdivian culture, which settled on the Santa Elena peninsula for many years. Here, Venus de Valdivia figurines were created as a tribute to the importance of people’s reproductive capacity.

As Abuela Killa says in the book, menstruation “is the only blood that flows in the world without the need to hurt anyone.” It is a blood that expresses a flow of life and it is a sign that a person is fit to enter this circle of giving life. That, to me, is quite sacred. How does the book contribute to these times of global feminist awakening and uprising?

“Society being ignorant to menstruation has caused women harm.”

The awakening has been taking shape for some time now. Since the ‘60s, it has been making visible this premise that the personal is political. I believe that tradition is very important and that these struggles allowed women to do what we do now, including being able to write and have a voice in public. Similarly, this book empowers girls. If she can have a positive connection with her body now, then I think she is less likely to later experience bad self-esteem.

I think that there is a lot of work to be done with young girls. That is why I believe in the importance of women’s circles — mothers, grandmothers and aunts — their own tribe of women who can give them guidance, especially when they experience their first menstruation.

Why is it important that people who don’t menstruate also educate themselves in this?

I think it is important for both men and women that we educate ourselves in these issues because, well, we inhabit this world together. Society being ignorant to menstruation has caused women harm. Not long ago, women were treated for “hysteria” because of how misunderstood we were. The ignorance of the other, or the negative construction of the other, means that at some point they can be subjugated.

In Tribu de Mujeres, Abuela Killa shares the phrase, “you cannot love what you do not know.” I think it’s one of the most important teachings and orientations of the book.