When Citlali Fabian first started her portrait series Mestiza in 2014, she unexpectedly remembered the skin whitening cream commercials from her childhood that had made her believe her dark skin and features were ugly. Fabian grew up in Oaxaca, Mexico, where close to half of the population is Indigenous, and is herself of Yalatec descent; yet, for much of her life, the now 29-year-old photographer struggled to reconcile with her Indigenous and European heritage.

In 2008, at the age of 19, Fabian set out on a journey to unearth her native roots: She participated in Yalatec celebrations in Oaxaca, reconnected with her cousins who had remained close to their heritage, and lastly, visited her parent’s hometown, the small Indigenous village of Yalalag. Here, she discovered an infinite source of purpose and inspiration that guided her camera, photographing the everyday landscapes and people for her series, I’m From Yalalag, and the town’s proud women for Mestiza, her ongoing project recently featured on The New York Times’ Lens blog.

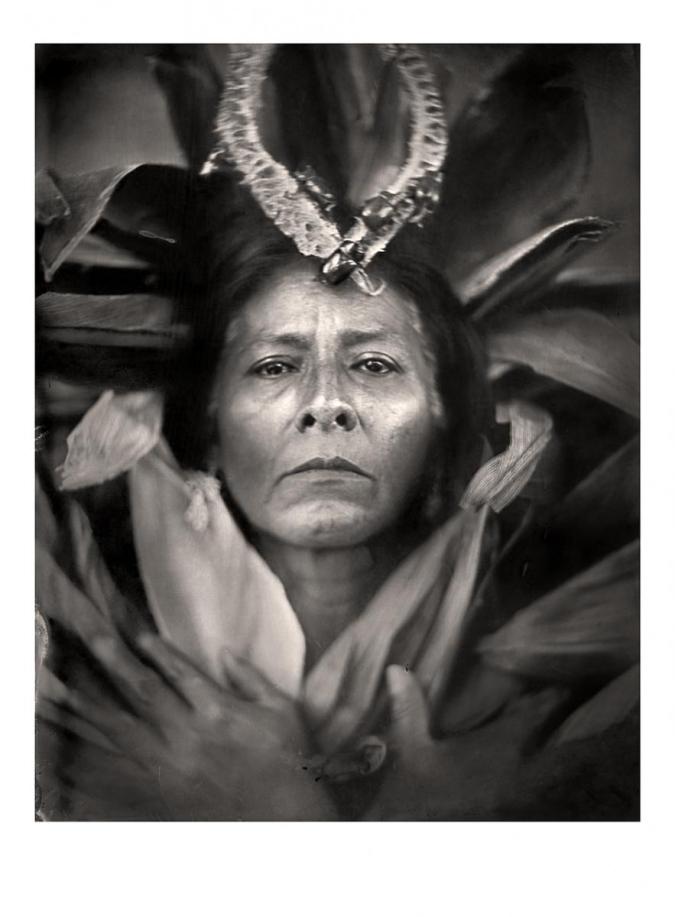

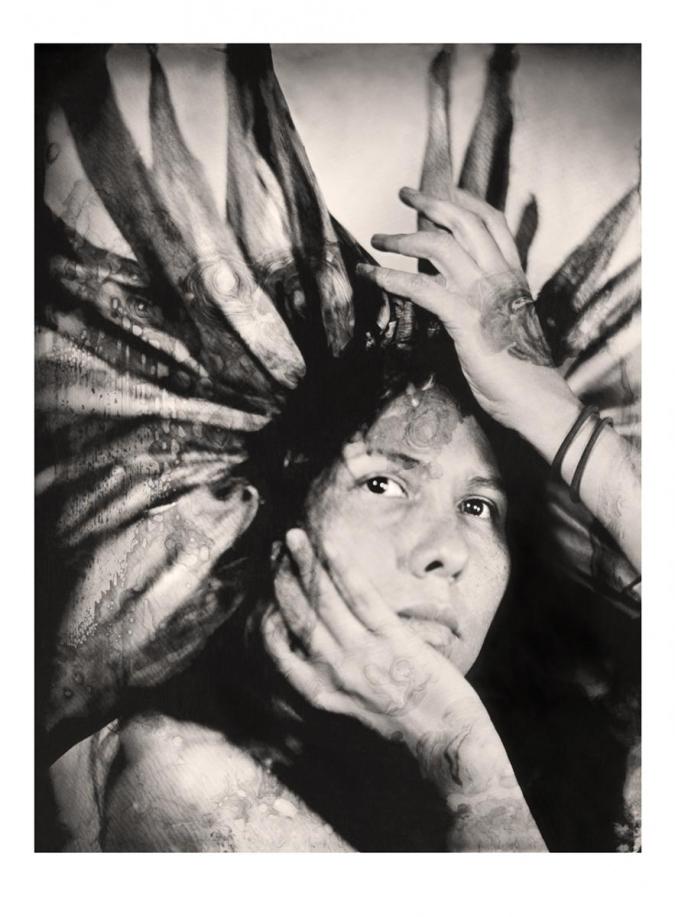

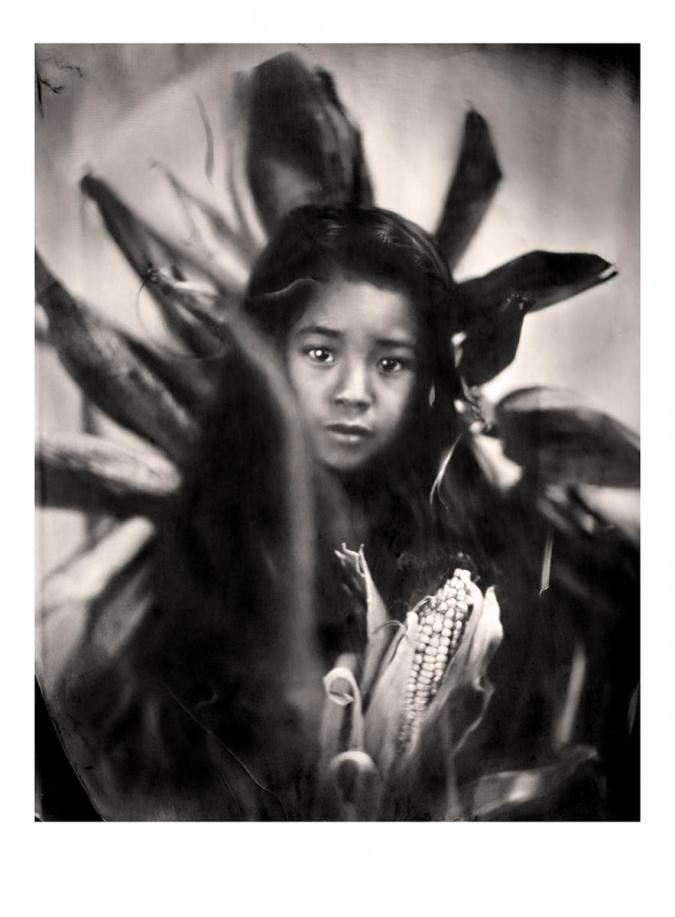

The protagonists of the series are Fabian’s close friends and family members, women and girls across three generations who identify as mestiza, a person of Indigenous and European descent. But in Oaxaca, where there’s also a sizable Afro-descendant population, she’s also documenting those who find themselves excluded from the mestizo binary. The images — black-and-white, dreamlike portraits shot on a large-format camera — tell a compelling story: One of contemporary Mexican women who have found strength in reclaiming the Indigenous past they were taught to be ashamed of.

“For me, it’s very important for our identity to be accepted in its entirety,” Fabian tells me. “I think it’s important that not only the spectator but also the participants — my friends, cousins, nieces, my mom, my aunts — should feel complete and happy with their being.”

Renouncing the Eurocentric standards of beauty she had grown up with, Fabian looked to accentuate the Indigenous features that make these women striking. Fabian employed a 19th century technique, known as the collodion wet plate process, that darkens any red and yellow tones in the picture. This process effectively darkened each woman’s skin, which Fabian said was a challenge for some of the women who had been told since childhood to keep out of the sun to avoid tanning. However, for other women, such as Fabian’s friend Tania, seeing themselves with a darkened skin tone helped them make unprecedented connections to their family history.

“In the case of my friend Tania, her reaction to the process was beautiful because she saw her grandmother in her portrait. She said, ’Wow, my uncles and father had told me I looked like my grandmother, but I never saw it before.’ And yes, in this photograph, you see her as a girl with Afro-Mexican features,” Fabian adds.

Throughout this series, Fabian uses a visual language that communicates her appreciation for the mestiza beauty seen throughout Mexico, but also the ancestral knowledge passed down through generations of her family. Instead of clothing the women with their traditional garments, Fabian preferred to recreate a poetic representation of their Indigenous values. Each woman, girl, and baby is adorned with totomoxtle, or corn husks, or corn, a staple of Mexican cuisine and, for Fabian, a visual metaphor of the Yalatec’s relationship with nature.

Fabian’s journey to reconnect with the Yalatec community and worldview isn’t complete; she explains she hopes to learn the Zapotec language her parents never taught her out of fear it would be an impediment to her social advancement. But in the meantime, her and her subjects stand with their heads held high, embracing the beauty of their differences.

“To be mestizo is to resist: it’s a way for us to resist and to refuse to be homogenized,” Fabian says. “For me, the interesting part is that it was a pejorative, a term for someone with mixed blood and who wasn’t pure. But in today’s world, who is?”