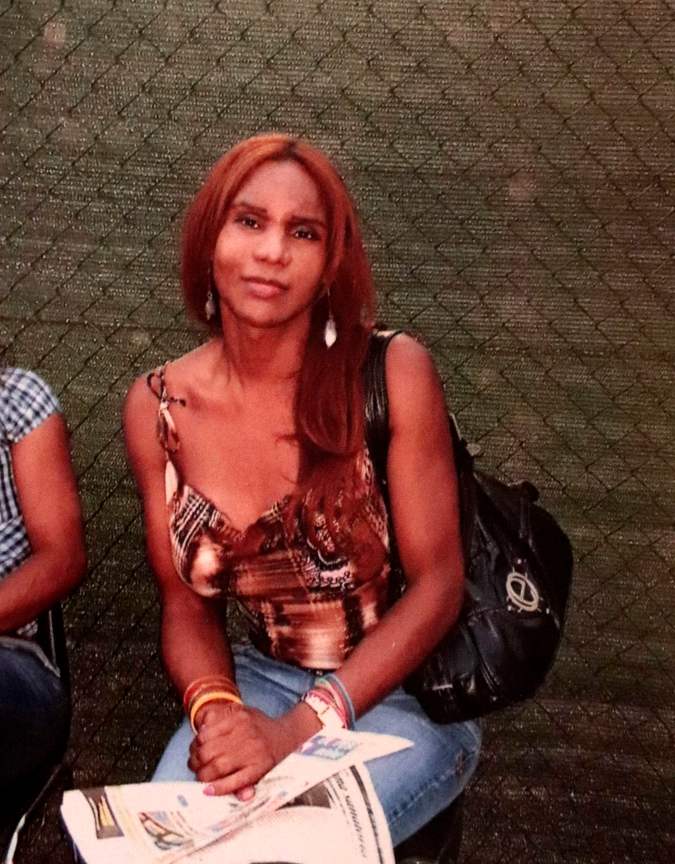

Cindy Núñez’s most treasured photograph dates back more than 25 years ago, when the revered, Colombian transgender activist was in the midst of her youth and making ends meet as a sex worker in Italy. In the weathered image, she poses coquettishly at the camera, surrounded by an idyllic forest landscape.

“My favorite is that photo because behind it there’s a lot of life.”

“I worked at the spot for 15 years, rain or shine, from Sunday to Sunday,” 60-year-old Núñez, known in Bogotá’s LGBTQ community as Mother Cindy, tells Remezcla. Like many other trans women in Colombia, Nuñez left in the ‘90s to try her luck in Rome’s lucrative sex work industry, aiming to save enough money for a comfortable retirement. There, many worked in the outdoors to cut costs.

“My favorite is that photo because behind it there’s a lot of life, a lot of stories: of men, of wars, of money, of humiliations, of scares, of running,” Nuñez says. The image also holds a lesson for younger generations of the hard work and forethought she put in to make her dreams of owning the four-story apartment building she lives in today come true.

Each photograph is a gateway to many stories. That’s what the Bogotá-born artist Manuel Parra, known as Manu Mojito, learned early on as he met the trans “mothers” of Colombia’s capital. These women shared with him vintage photographs from their family albums — of parties, beauty pageants, pride parades and of complex lives that had gone unnoticed by most of society.

Then, almost eight years ago, Parra conceived the idea of Colombia Trans History. He imagined an archive of images, taken from the photo albums of trans women, that could weave together an alternative telling of trans women’s history in relation to what had been narrated by the predominant media of the times, which usually framed trans women as criminals.

“The trans history of Colombia has been marked by sensationalist newspapers and transphobic news,” the 31-year-old artist tells Remezcla. “The media has criminalized their history, so what we wanted to do is to collect their photographs and to tell their history through their eyes.”

“The media has criminalized their history.”

Dozens of trips across Colombia later, Parra has collected more than 40,000 images, videos, diary entries and other personal documents — some dating back to the ‘50s — that make up what is easily the largest archive of trans women in the South American country. These are currently stored in the Bogotá offices of the nonprofit Fundación Arkhé, open to the public.

But recently, Parra opened the Instagram account @ColombiaTransHistory to share these stories with a wider audience online. There, he pairs vintage photos with detailed descriptions of the women that appear in the image, the struggles they faced and the roles they took on in their communities.

For decades, traditional media refused to report on trans women except for the occasional article that described a brutal killing. But these articles weren’t just sensationalist; they also attempted to justify the crimes made against them by charging the deceased of illegal activity. “Their history was marked by what society perceived of trans women and not by what these women actually lived,” Parra says.

The implications of these erred narratives, which continue till this day, are dangerous, says lawyer Matilda Gónzalez. Despite the changes in the times, stereotypes, tokenisms, censorship and tropes that prevail in primetime television and other media provoke grave misunderstandings of trans women and undermine their agency and rights — all of which contribute to transphobic violence.

“We were imprisoned two to three months for having painted nails.”

“All the studies on crimes motivated by prejudice … show that these situations are systematic and that they are nourished before, during and after the act of violence by prejudices and stereotypes,” Gónzalez tells Remezcla “If you meet someone in a bar and they realize you are trans, the fact that they want to kill you is legitimized because we’re not seen as equal or it’s believed there’s something wrong in liking trans women because it affects their identity.”

This is especially alarming in Colombia, a country ranked fourth in the world for the number of reported homicides of transgender people.

What is powerful about Colombia Trans History is that the stories are told through the voices of the ones who lived them and reflect on the good as well as the bad. Between stories of romantic partners and trips across Europe, Nuñez recounts how in the ‘80s and ‘90s in Colombia, police persecuted, falsely imprisoned, tortured, disappeared and killed trans women with impunity. This persisted despite a presidential decree issued in 1980 that struck down a law against “homosexual acts,” which was used to target trans women.

“We were attacked for no reason. Sometimes we were imprisoned two to three months for having painted nails or because we had on earrings or they saw us go inside somewhere with a man,” Núñez says. “It was a dog’s life.”

This criminalization of trans women is evident in a photograph of Nuñez before she travels to Italy, says Gónzalez. In the image, Nuñez is forced to wear men’s clothes and place her hair back into a ponytail to avoid persecution from police and airport officials. “This also tells a history of criminalization, of having to hide to travel,” the lawyer says.

“It’s super important to start to talk about the historic reparations that remains pending as a society and as a country,” Gónzalez says. “I don’t think this is only about recounting so that we know what happened, but rather there has to be reparations and a recognition of these human rights violations.”

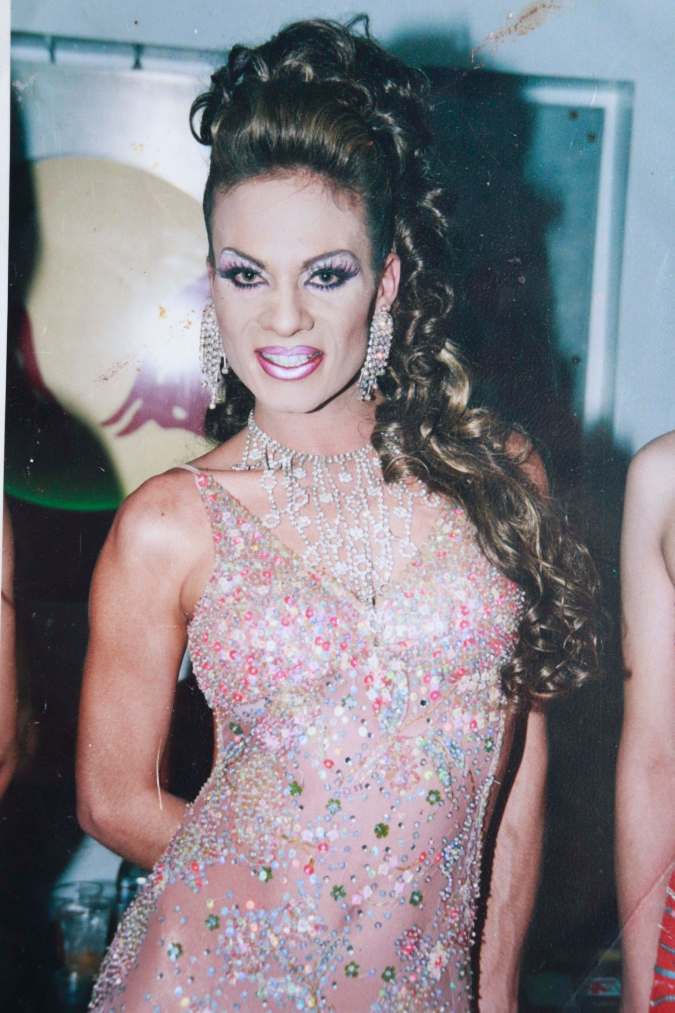

Amid these stories of persecution and struggle is what Parra calls the “other history” of how trans women found ways to protect their joy despite the human rights violations they faced. It’s telling that the women in most of the archive’s photographs are pictured happy and smiling. They’re often at clandestine bars and clubs they propped up as a safe space to have fun.

“This happiness, these bars, these pageants were all methods of resistance.”

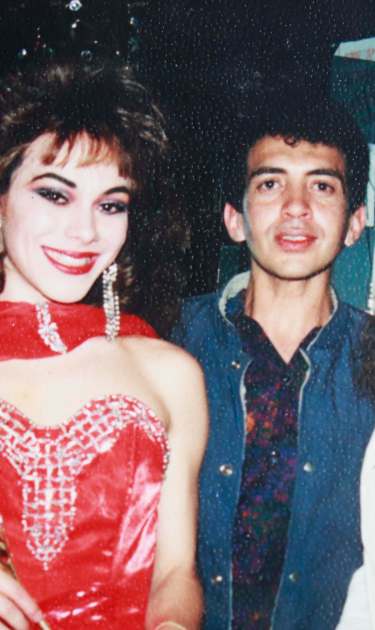

One such club was Dandi in downtown Bogotá, immortalized in the archive, where female impersonators and trans women competed in beauty pageants.

“To create these secret spaces went against society,” Parra says. “This happiness, these bars, these pageants were all methods of resistance.”

These are the types of stories Nuñez says she hopes people can learn from. For her, it’s important for others to understand the struggles trans women experienced and remember those who lived through these times — some of whom didn’t survive.

Looking at the photographs, Núñez reflects that she has lived a long life that “would take hours to tell.” But when it comes down to how she wants to be remembered, she hopes people will come to know her for her glee, her high spirits and her humor.

“I want to be remembered as I am,” she says.