The heart of Lilliam Rivera’s debut YA novel, The Education of Margot Sanchez, is its familiarity. Aside from the title’s Lauryn Hill nod, there’s the family-run neighborhood supermarket and an escalating series of sibling-parent power plays. There is the purgatory of being grounded, the drama of a love triangle, and the freedom of the summer concert. (That last one goes double if you’ve had the pleasure of seeing Calle 13 live, which inspired a chapter here.)

In sum, it has many of the elements of a classic teenage coming-of-age story. But Rivera also explores weightier subtext here. Her protagonist, Margot, is a Nuyorican growing up in a “rich-adjacent” household in Riverdale, several neighborhoods over from the South Bronx. In Margot’s world, race and class are writ large, as per YA; beneath them is the generational ripple effect experienced within families that aspire to assimilate. Ultimately, the story is an interrogation of the ways gentrification and the ideals of assimilation can shape a young teenager.

Rivera paints Margot’s story with similar thematic colors to her multiple-award-winning short stories, which largely focus on women living through the challenges of the South Bronx. It is this approach that garnered her a 2016 Pushcart Prize for her story “Death Defiant Bomba, or What to Wear When Your Boo Gets Cancer,” and that prompted the LA Times to name her a Face to Watch in 2017.

We caught up with Lilliam to hear about how her personal experiences inform her writing and making space for protagonists of color in the YA world.

How was writing YA different from writing your previous short stories?

My short stories are always about female characters who are flawed in some way. And I get that with Margot Sanchez, just like my short stories. But there’s that immediacy when you’re writing that young adult voice. I love that. There’s no time for meandering about things; everything’s really urgent, and now. Even if it’s just going to the beach. And what I love about writing contemporary young adult novels is that you are dealing with how class and race plays with your role in your family.

She’s going to assimilate and copy the people who are in power. And usually the people in power are white.

Margot has a wonderful line early on in the story: “We’re not rich. We’re rich-adjacent.” Can you tell me about that idea?

There’s this question about assimilation: her parents’ pursuit of it is to constantly make sure that they appear powerful, or rich. They live close to people who are rich, so everything about them is rich-adjacent. They have two supermarkets, but they’re struggling a bit – yet they’re sending her to a prep school; she’s not a scholarship kid. Her father makes sure she’s aware that she’s going to this prep school, and that there aren’t that many people of color there, and that that’s a good thing.

So she’s just trying to navigate that world. She’s going to assimilate and copy the people who are in power — and usually the people in power are the white people. Because that’s what her parents are teaching her to do.

How much of the story comes from personal experience?

I thought of what it’s like when kids finally see their parents as people with flaws and unfulfilled dreams.

It’s not autobiographical. But my first summer job was working with my father. He worked as a nurse’s aide at a private hospital in Manhattan. I was fourteen; at that point, my father was everything to me. He made all the decisions; he was the man of the house. And then, I got to see him do humbling work. For Margot, I thought of what it’s like when kids finally see their parents as people with flaws and dreams – unfulfilled dreams. That moment where they’re humans, and not just your parents.

And my brother attended a boarding school when I started college; he was offered a scholarship. Years later, he would tell me what it was like; he was sharing rooms with people who had, like – millions of dollars! And he’s coming from the projects. I don’t know what that must have been like – to have to cope with that. But it was a great opportunity! You gotta take that opportunity, right?

I imagine there was some … forceful encouragement? From your parents?

[Laughs.] Like, “You cannot fail!” Right? Like, there is no option. I felt that pressure when I went to college. I withdrew because it was too much for me. And my parents were in shock! They were like, um, you don’t have that option. That’s not even possible. This is the opportunity to excel, you don’t have an option not to.

And I feel like a lot of Latino kids, kids of color, have that pressure. The burden of like – ‘You’re gonna save us, right?’ Definitely Margot has that.

She has another interesting line, when her love interest gives her some flack for that: “He wants to peg me with everything evil. If you don’t live like him then you’re trying to be white or rich or something other than what you are. I don’t even know what I am yet. I’m just maintaining.”

That’s one of my favorite scenes, with the two of them on the roof. Rooftops are so magical – things are always going down on the rooftop.

A lot of Latino kids, kids of color, have that pressure. The burden of ‘You’re gonna save us, right?’

I grew up the first one to go to college, out of my family. I grew up with a large Puerto Rican family, and we all lived in the South Bronx. People want you to succeed. Your family wants you to succeed – but not too much. [Laughs.] They’re like, oh, you sound white – if I would talk [a certain way]. Or if I listened to other music that wasn’t Latino music, if I’m listening to rock. There was always that bit of side-eye, you know? But, you know, I was always just trying to be. Whatever that was. A lot of teenagers – you’re just trying on certain things. You’re trying on what you want to be like. And it can be a mixture of all different things! It could be reggaeton and – Taylor Swift. [Laughs.] All of it.

But, there is that little tinge – “I want you to succeed, but not that much. I want you to succeed, but remember where you’re coming from.” And there’s no doubt, I wear my Bronx pride wherever I go. There’s definitely no denying that. But there is that moment where you’re just like – oh, if I’m gonna make it, maybe I have to let go of all of that. Let go of my Latino culture and all that. And I just – I don’t. I don’t want that. Even with my own kids, even though they’re California girls – I let them be so aware of where they’re coming from, being Puerto Rican, being Latinas.

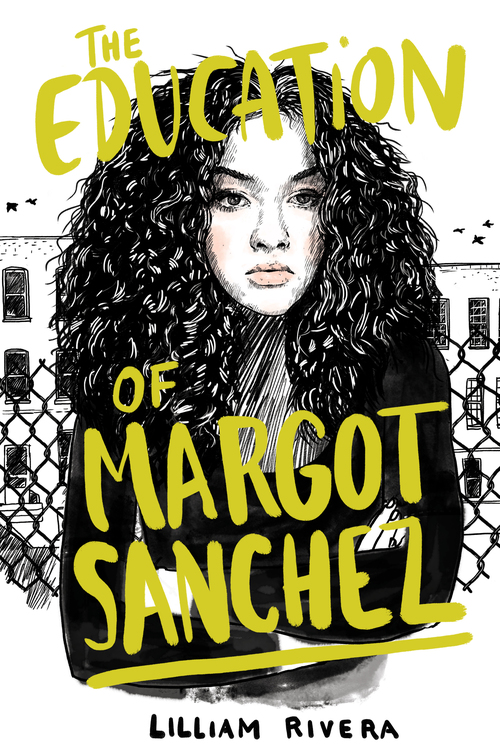

The cool thing that I have witnessed is that a lot of Latinas – and even Latinos – have been reaching out to me and saying how much they love just even seeing the cover. That to me is really awesome. I even have people from Puerto Rico sending me gifts because they love the book so much. Like, here’s a mug with the Puerto Rican flag. [Laughs.]

But it’s been really cool to see – even young kids. I’ve loved going on school visits and talking to them about it – even talking about representation in books. That to me has been the highlight in all of this.