As one of the few Filipino American psychology professors in the US, it can get lonely. I am the only Filipino American professor on my campus and one of the few tenured Filipino American professors in New York City (and on the East Coast in general). When I first started writing about Filipino American issues over a decade ago, I found myself constantly fighting with scholars (especially peer reviewers) who argued that I should concentrate on issues affecting the pan-ethnic Asian American community, instead of focusing specifically on Filipino Americans. Whenever I wrote journal articles or essays, I always had to explain who Filipino Americans were – outlining colonial history, phenotypical appearances, and socioeconomic experiences in the US. I relied on interdisciplinary readings because there was so little written about Filipino Americans in social sciences. I turned to Latinx and Black American mentors, who validated my feelings of marginalization within the Asian American community. And I was fortunate to work with one Chinese American mentor who encouraged me to pursue my interests in writing about Filipino American Psychology.

While there have been several amazing Filipino American scholars who have emerged across multiple disciplines in the past ten years or so, it is still a rarity to see a Filipino American professor — in a tenure or tenure-track position — who studies issues of concern for Filipino American people. In fact, in a study that I conducted with Dr. Dina Maramba in 2010, we found that there were only 113 tenured or tenure-track Filipino American professors in social sciences, education, and humanities in all of the U.S. As a reference point, there are 45 full-time professors in my Psychology Department alone (mostly white) and 415 full-time professors on my campus with 15,000 students. So, to only have a little over 100 Filipino American full-time professors in the US across these disciplines (when there are over 4 million Filipino Americans in the US), is both disproportionate and unfortunate.

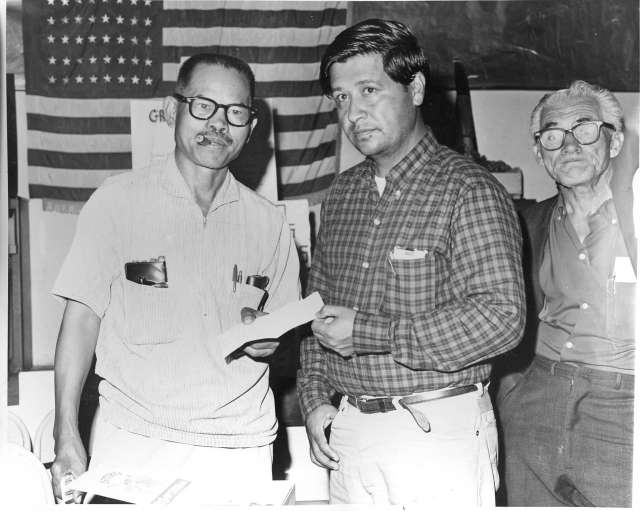

Because of all of this, I was so excited when I first learned about Dr. Anthony Ocampo and his research on deconstructing race for Filipino Americans. Dr. Ocampo is a tenure-track assistant professor of sociology at Cal Poly Pomona. His first book, The Latinos of Asia: How Filipino Americans Break the Rules of Race describes how Filipino Americans’ experiences with race and racism is influenced by social context (e.g., friendships, neighborhoods and communities, or even school environments). His research answers many of the questions that I had when I was first a student trying to understand Filipino American identity- unpacking issues related to Spanish and American colonialism, whether or not Filipinos are “Asian enough”, and whether or not Filipinos should continue to be classified under this pan-Asian umbrella. I was fortunate enough to catch up with Dr. Ocampo a few days after he gave a book talk at the Filipino American National History Society (FANHS) national conference in New York City.

RELATED: 10 Reasons Why Latinos and Filipinos are Primos

Tell me about what inspired you to write The Latinos of Asia.

“I always wondered why writers hardly ever talked about the connections between Filipinos and Latinos, even though they talked about Filipinos’ connections to other Asians.”

There’s a quote by Toni Morrison that pretty much captures why I wrote The Latinos of Asia. “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” I was born in LA, and I grew up in Eagle Rock, a neighborhood with mostly Filipino and Latino immigrant families, and so I literally saw the cultural similarities between our groups every day growing up: our names, our family dynamics, [and] and for many of us, our religion. But when I went to college at Stanford, people automatically lumped me into the Asian American box. When I was growing up, Filipinos never had to think of ourselves as being Asian because there were so many of us. And at first I thought this was weird for others to automatically assume that I’d identify that way. I took lots of different classes to try to understand the meaning of Filipino identity. And throughout the books I read, I always wondered why writers hardly ever talked about the connections between Filipinos and Latinos, even though they talked about Filipinos’ connections to other Asians. I wrote this book because I wanted to highlight this part of the Filipino American story that I felt was missing.

Having personally never checked an “Asian American” box on any form until I left the state of California, I can certainly relate to this. As you know, Filipino Americans are the only Asian American group in which it has been required (since the late 1980s) to have listed as a separate group from the Asian American umbrella. So, I imagine that many California pinays/pinoys have had similar experiences. Tell me what the reception been so far from the Filipino American community?

The reception has been overwhelmingly positive. I’ve gotten emails from Filipinos all over the country — Texas, Illinois, New York, Pennsylvania, even Arkansas — and they’ve written to say thank you for writing a book that finally captures their experiences. A lot of them have shared their frustrations when other people just don’t get what it’s like to grow up Filipino. To have racial experiences that overlap with both Asians and Latinos. To know that race isn’t just about something as simple as geography. It’s been so great to hear them say that they feel more empowered to share their story. I’m so happy to know that the book has been such a source of validation for so many young Filipino Americans. Of course, there are some Filipinos who disagree with what I write about in the book or say that the book is too much about the LA experience. But I hope that just inspired them to pick up their pens and share their stories.

And how have Latina/os and East Asians reacted to the book?

I’ve gotten more responses from Latinos than East Asians. There are so many Latinos who have mentioned that they have close Filipino friends that they first assumed to be Latino themselves when they first met them — this idea that Filipinos seem to blend in seamlessly into Latino situations. Some East Asians I’ve met have said they’d always felt Filipinos were “kinda different” from other Asians but they couldn’t necessarily put their finger on it until they read my book.

Yes, I have certainly had similar things said to me by Latina/os, especially from Mexican Americans who have expressed a kinship with Filipino Americans. I’ve also had East Asians say that Filipinos were the “Black Asians” or the “Asians with soul”. Sometimes they would cite more positive qualities (such as being able to dance or sing) but they often would cite negative stereotypes (such as Filipino being “thugs” or “gangbangers”). Have you heard things like these before?

Heard it all before! Think about those racial catchphrases — the Black Asians, the Asians with soul, or the Latinos of Asia. They suggest that Filipinos are at the margins of Asian American community. Even if used as a compliment, these catchphrases implicitly tell you that Filipinos can’t possibly be the “real” Asians. In the book, some of the Filipinos I interviewed talked about being labeled like this. On the surface, one might think, “Oh, it’d be cool to be referred to as the ‘Asians with soul.’” However, in reality, it also meant Filipinos were seen as less smart in the college classroom or less qualified in the workplace, relative to other Asian American groups.

I know you went to Stanford for your undergraduate and MA degrees and UCLA for your doctoral degree. Were there other Filipino Americans around you? What was that experience like?

“Living alongside Mexican Americans made the history of Spanish colonialism more salient in Filipinos’ minds because they could literally see the similarities in their cultures.”

Being a Filipino American at Stanford was tough. There were a lot of other non-Filipino Asians at Stanford — Chinese, Korean, Indian, even Vietnamese — and there were a lot of Mexicans Americans. At Stanford, I happened to find my home with the Latino and African American students. I was even part of Gamma Zeta Alpha, a Latino fraternity at my college. I just felt like I belonged in those circles more. In my freshman class, there were about 20-something Filipinos in the entire class. There were more Filipinos in my elementary school classrooms than there were at the entire university, it seemed. In most of my classrooms, I was usually the only Filipino voice in the room, and so I always felt pressure to be the “representative” for my entire community. College is hard enough. I don’t think anyone should ever feel that kind of pressure. Plus, no one person can be representative of the entire community anyway. Luckily, I had a really tight knit group of other students of color — Mexican American, hapa, African American, Jamaican American, you name it. That was really important because we could all relate to the experience of being the “only” in our classrooms at Stanford. Having those friends made it less lonely.

At UCLA, I was the only Filipino American graduate student in the sociology program. In fact, I don’t think folks in my department could even name another Filipino who’d ever attended the UCLA sociology PhD program. In that sense, it sometimes made it difficult to convince others of the importance of studying Filipino Americans. So many didn’t even realize that Filipinos were the largest Asian Americans in the state.

That’s so unfortunate that so many non-Filipinos in California don’t know about Filipino American history, even though Filipino Americans are the largest Asian group in the state. What about other parts of the country? Would you say there are any regional differences for Filipino Americans on the East Coast, the Midwest, or South, or even in Alaska and Hawai’i?

Absolutely! I don’t want readers to think that I’m trying to write the book on Filipino Americans. I wrote a book on Filipino Americans. Our experiences are so incredibly diverse that they can’t possibly be captured in just 200 pages. One thing that makes California’s [experience] distinct is their proximity with Latinos. Living alongside Mexican Americans made the history of Spanish colonialism more salient in Filipinos’ minds because they could literally see the similarities in their cultures. I don’t think that happens to the same extent in places like Hawaii or even the East Coast. However, as our country becomes more and more “Latinized,” I imagine that these connections between Filipinos and Latinos will become more and more apparent to Filipinos and others throughout the country, not just California.

Speaking of Filipino Americans on a national level, you recently spoke at the Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS) which is the largest gathering of Filipino American scholars in the US. What was that like sharing your work with some of the most influential Filipino American scholars?

Magic. I would never have been able to write this book without the Filipino American community activists and scholars who blazed the trail in their disciplines. Dorothy Cordova and her late husband Fred Cordova archived the lives of some of the earliest Filipino settlers. Dawn Mabalon was my first and only Filipino American professor in college — she was the one who inspired me to pursue a PhD in the first place. You and E.J. R. David are among the few psychologists in the United States who dedicate their careers to writing about Filipino American psychology. And to have all of these people in one single room listening to me present my book — and voicing their love and support — it was truly a magical experience. Honestly, it was life changing in the sense that it has inspired me to push my work on Filipino American communities to the next level. I don’t just want to write about Filipinos. I also want to help organize the community, especially the next generation of young Filipino Americans who don’t necessarily have the chance to learn about their history.

Yes, the community definitely will benefit from you organizing and mentoring this rising generation of Filipino Americans. Speaking of which, who were your mentors? Did you have any Filipino mentors?

Dawn Mabalon of San Francisco State is a hero. Her unwavering commitment to documenting Filipino American history is going to impact Filipino American students and communities for generations to come. Plus, she’s also a community organizer. That’s dope. Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales, another SFSU professor, is inspiring thousands of Filipino students from the kindergarten to doctorate level to embrace their Filipino identity. She’s inspired hundreds of Filipino Americans to become educators at their local schools and communities. I also look up to people like Robyn Rodriguez, a sociologist at UC Davis, who has used her research to positively impact the lives of Filipino immigrants. I can’t say enough about you and EJ David for creating a framework in the psychology field for young Filipino Americans to understand their experiences. Ultimately, my role models in academia are those Filipinos who are able to do cutting edge scholarship without compromising their commitment to the community. I don’t know how they do it, but I’m learning every day.

You’re absolutely right that we do have some dope Filipino American scholars who are doing everything they can to make sure our community is represented. I feel there is a lot of pressure for Filipino American professors, mostly because there are so few of us in academia. Why do you think that is? Do you think this will change in future generations?

I think Filipino Americans don’t go into academia because it’s scary. It’s unchartered territory. And I think those that end up going in realizing that it’s not a very safe space. Our experiences and our perspectives aren’t validated by professors. Professors often can’t see the importance of studying the Filipino American experience, and as a result, they aren’t lining up to mentor us. Do you know how many professors there are that can’t even spell the word “Filipino”? I can’t tell you the number of times a famous professor has written “Philipino” or “Fillippino.” I know it seems small, but for a young Filipino in graduate school, this kind of thing sends a message that they just don’t care. They also don’t get our strong commitment to the community. Many think that activism and community work is antithetical to intellectual pursuits, which I think is total BS. That’s why we need Filipino American role models.

One of the things that has attracted people to your book is the title. If you were in charge of the US Census, what would you do? Where would you put Filipino Americans?

I’m all for Filipino Americans being our own category! Real talk though, I also know that creating panethnic alliances — like Asian American, Latino, Native American — are important for political organizing.

In my book, I talk about how Filipinos don’t fit the rules of race, and that means that a lot of Asian American causes often forget Filipino Americans. In the New York Times, there was this short documentary “Conversations with Asian Americans on Race,” and no Filipinos were included. I was like, WTF, really?

On the other hand, after writing the book, I get the question all the time: So should Filipinos be recategorized as Latino? There are some old documents from the Census Bureau that indicate that Filipinos could have been lumped in with Latinos, but I think that would come with its own set of problems too. Just think about the United Farmworkers. Filipinos were a central part of creating that organization and then were soon forgotten. The UFW is now seen primarily as a Mexican American organization. Filipinos could get marginalized from that category too.

Realistically, I’m cool with Filipinos remaining part of the Asian American category, but I just want people to draw on my book to think harder about the ways racial categories actually work on the ground. Maybe learning about the Filipino experience can help all groups develop a greater understanding of the cultural factors that help, as well as hinder, unity between different groups.