Death has consumed my thoughts for the past few years, so much so that it’s made me abandon my once-atheist identity and find a belief in God, in heaven. Somewhere, anywhere, really—where my Abuela’s soul could rest safely, surrounded by goodness, until mine joins her. She’s not dead yet, though. She was diagnosed with stage four cancer in 2021, went into remission, and has now decided to let God’s will be done the second time around. She didn’t seek a biopsy for a new tumor because it wouldn’t change the outcome.

I’ve struggled to accept that she’s at an age where a fatal disease feels less like a tragedy and more like the inevitable fate one can humbly accept while going about their day-to-day life. Nevertheless, I feel guilty about the fact that she has died in my head hundreds of times, even as we talk on the phone and she asks about family members I haven’t seen in decades since moving from Colombia or people in my daily life. “They’re good, Abuela!” I say, exasperated, because she accepted her diagnosis with more resilience than she did me not staying in touch with people once integral to our lives.

As Día de los Santos once again comes around on November 1st, I’m reminded that remembering the dead is an act of love. And I sneakily used the topic of this holiday as an excuse to ask Abuela what I’ve been too scared to ask her: Are you afraid to die?

“Todos estamos aquí en una misión,” she says, reminding me that we’re all here on a mission. Regardless, she thinks “anyone who has been in a mother’s womb has a reason to observe Día de los Santos.” It’s not exactly an answer. But then again, there isn’t one that would please me besides a way to get her to live forever, or until I die.

To better understand Día de los Santos, Día de Muertos, or any holiday honoring our dead, I sought out two community leaders in Portland who help people face the mortality of their loved ones, and ultimately, themselves.

Martha Guembes, Honorary Consul for Guatemala in Oregon, tells Remezcla she has been partaking in Día de los Santos since she was a little girl in Guatemala, as well as Día de Muertos the following day on November 2nd. She was raised celebrating the former as a way to remember loved ones in heaven, and the latter to help those stuck in limbo. She no longer believes people’s souls can get stuck in transition.

At 63, she confesses that grief only gets harder because of how normal experiencing it becomes, and each death serves as a stronger reminder that her time is coming. One of her yearly traditions for Día de los Santos is building an altar for all her loved ones and lighting a candle for each of their faces, though she says her home also has year-round dedications to them. This year, Guembes will be remembering her siblings, her mother, grandmother, aunts, and people she describes as “familia de mi corazón.”

Guembes’ relationship to death and grief is a little different from most because she has served as a spiritual guide to her community, aiding those who are dying or in the process of losing someone. “I’ve been around many people when they take their last breath, cuando mueren, at that moment,” she says. “There have been many people I’ve helped through that transition. Their families are back in their countries, right? They don’t have the support, and I do understand that because I have been there. I understand the grieving process, and I feel very, very comfortable seeing someone pass on.”

In fact, Guembes hasn’t just comforted people as they close their eyes for the last time, but she was inspired to capture the essence of those final moments.

The spiritual guide has photographed some of the families she has helped through the transition process, with their permission, and she says the photos can be very healing and helpful to cope with their emotions. Guembes says her culture taught her about the sacredness of death and to respect it from an early age. She was taught to honor and acknowledge grief rather than hide from it. “We embrace el duelo (grief), and we don’t hold it in,” she says. “In America, you’re taught to suppress these feelings and difficult emotions.”

For Guembes, she says the Latin community in Portland isn’t as large as in other cities, but it has been gradually growing, and they all find each other as a way of keeping their heritage alive. And when a person close to Guembes dies, she practices “luto,” which involves praying for the departed person’s soul for nine days, wearing black, and even avoiding listening to music as a way of keeping a clear mind and processing pain.

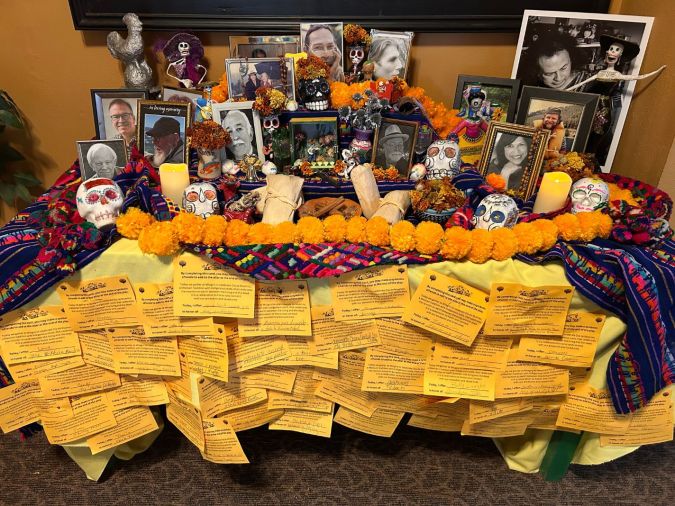

Dañel Malán-González, executive artistic director of Milagro Theater, tells Remezcla she helps lead a team of artists that help community spaces build altars to remember and honor the dead for Día de Muertos. She founded the Pacific Northwest’s only Latino theater company in 1985 with her husband. And the theater has showcased a special altar for Día de los Muertos dedicated to its community for nearly 30 years.

In the early years of the theater, González remembers an actor who was diagnosed with stage four cancer and loved the theater so much he wanted the venue to host his assisted suicide, which was legal in Portland. “We were like, ‘No, we don’t really want to have your ghost around,’” she says. “But we did have his memorial, and we’ve actually hosted a few other memorials for our theater community. In fact, we have one coming up on November 9.”

González says her artistic influences—and the way she has been inspired by death—both come from her mother, who was an art teacher and died untimely due to alcoholism. And this year, the theater will host a theater production for Dia de los Muertos, where audience members can remember their dead loved ones as she does through offerings.

And when it comes to death, González thinks people place too much focus on fearing death rather than ensuring they accomplish all they need to in this life. “Folks should aspire to do something that creates some form of legacy for their friends, family, or community,” she says. For her, that’s Milagro Theater and all its traditions, which will be carried on through her daughter, who is currently serving as president.

Guembes and González are a reminder that the best way to honor death is by not shying away from the topic or our own personal feelings. The grief is real, so are the ailments that take away our loved ones. And if we are to honor the ones still living, like my Abuela, we should embrace living in the moment until we have to remember them on Día de los Santos or Día de Muertos.

So today I’ll pick up that phone and listen to my Abuela, never taking her voice for granted, and embracing the moments that I have with her, even if it’s to talk about family members I haven’t seen in decades since moving from Colombia or people in my daily life.