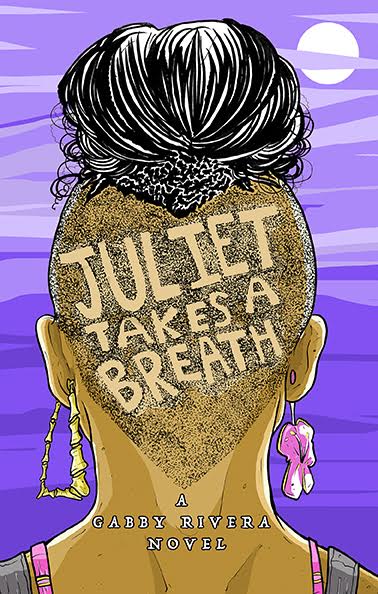

With her debut novel Juliet Takes a Breath, writer, youth mentor, and Editor at Autostraddle, Gabby Rivera makes an important addition to a small but growing group of young adult novels with queer protagonists of color. Published in late January, Juliet Takes a Breath tells the story of Juliet Milagros Palante (aka La “Sin Verguenza”), a 19 year-old Puertorriqueña from the Bronx who comes out to her family just before heading to Portland to intern for her favorite feminist author, Harlowe Brisbane. This coming-of-age tale, loosely based on Rivera’s personal experiences, is truly exceptional in that it not only brings complex issues to the forefront—coming out to your traditional familia, the erasure of intersectional feminist narratives, painful crushes on hot librarians—but also beautifully maps out radical possibilities for queer Latinx youth and queer people of color.

Rivera highlights the struggles of code switching between different worlds, as a Latina who is queer, and as a Latina in white-dominated queer spaces, in a way that is profoundly poetic, witty and heartbreaking all at the same time. We caught up with Rivera to learn more about her process and inspirations.

Can you tell me about the process behind writing ‘Juliet Takes a Breath’ and how the story came together?

I didn’t think at all to turn it into a novel. The author I [interned with] kept saying, ‘One day you’ll write about this.’ One of my writing mentors, Ariel Gore, also told me to send a story of my time in Portland. The first iteration of Juliet Takes a Breath was devoid of all the things it has now. It didn’t have identity or politics, or Latinx ancestry revelations. [Another mentor, Latina writer, producer and filmmaker] Linda Nieves-Powell said, ‘I like this but where are you? I don’t see Gabby Rivera in this at all.’ There [was] no meat, no layers, no complexity…and I would think ‘Is this another one of those stories where a white person saves a young person of color from the hood? Am I writing that story?’ I had to do some serious soul searching and evolving in my personhood and politics. As I asked myself those questions, Juliet really came alive and the purpose of it, connecting with queer youth of color, became clearer to me.

The book is really fun to read for folks of all ages, but it’s especially accessible to youth. Did you have a set audience in mind when writing this?

I guess the first time around I figured this would be a book for girls—girls that like girls, girls that are Latina, girls that want a different kind of story that they can relate to. As the book evolved, audience-wise, I wanted to reach people at the beginning of their journey. I wanted to really show [readers] that person who isn’t ready yet, what it’s like to be put into that world and into that context, be asked about pronouns, how you identify, or be asked about gender essentialism for the first time. What is it like to encounter beautiful humans who defy everything you’ve been taught about gender and sexuality? That’s the kind of audience I was looking for and wanting to talk to. It’s okay to be on your path, it’s okay to be learning, and it’s okay to not know.

Finding spaces where what you know about your own people are challenged and expanded is necessary.

There are a lot of images of spaces—libraries, train cars, workshops, parties—and Juliet is constantly existing in multiple spheres, some of which erase part of her identity, some of which are free and liberating spaces. What are these kinds of free spaces for you in your own life? Can you elaborate on the importance of queer Latinas occupying these spaces?

Walidah Imarisha and Adrienne Maree Brown [editors of Octavia’s Brood] held a workshop at the Allied Media Conference called “Black and Brown Women Write,” and it was really transformative. Finding spaces where what you know about your own people are challenged and expanded is necessary. Also, it’s necessary for us Latinos, Afro-Latinos, and black people to be things like beekeepers or neurosurgeons. We’re not allowed to be a lot of things. [Juliet] learns that even in her own family there’s a history of rebellion, social justice and queerness. Finding those links in your own family is revolutionary and it changes the way that you look at yourself and your place in the world. Our narratives are so narrow. It’s almost like we can’t dream beyond what we’re given until we meet others like us that are doing different or interesting shit. [Same goes for] queer spaces. Until you’re in a queer space, you almost can’t imagine it. I needed [Juliet] to be complex and layered so that people wouldn’t say things like ‘Oh, I’m reading this book about this little Latina from the hood.’ Even that little Latina from the hood is interested in so many things and is much more complex than any representation ever gives her credit for…It’s the adding onto [models we’re given], so that you have an expanded worldview where you can see yourself doing other things.

You can buy a copy of Juliet Takes a Breath and/or inquire about donating a copy to queer Latina youth or youth of color here.