The Garinagu – plural for Garifuna – have a rich history, reflected in many ways, particularly through food. The savory, multi-step – sometimes multi-day – creations echo the complex, yet beautiful background of a people who have survived being uprooted and exiled from St. Vincent to settle along Central America’s Caribbean coast.

Never enslaved, the Garinagu reside in Belize, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Honduras, with a small group still in St. Vincent and the Grenadines. However, many have migrated to several cities in the United States to create communities in Texas, Los Angeles, Chicago, New Orleans, and New York City – home of the largest Garifuna population outside of Central America. Most estimates declare the number of Garinagu in NYC at more than 200,000, with a majority settling in the South Bronx.

And despite the lack of Garifuna restaurants in the city and only making up a sliver of New York’s total population, this community has made its mark in a few boroughs. Through conversations with three young women, we learned how the kitchen is a gateway to other aspects of Garifuna culture.

For Bronx native Catherine Ochún Soliz-Rey, preserving Garifuna traditions and culture is a passion. The women’s empowerment coach and influencer invests a large portion of her time expanding Wabafu Garifuna Dance Theater, a collective founded in 1992 by her mother, dancer Luz F. Soliz, that preserves the richness of the culture and history through dance, music, and storytelling.

“Part of our job to preserve the culture is by sharing so that people can know who we are,” Soliz-Rey says. “It’s difficult but we have to bring more awareness to who Garifuna people are and that’s why I find it so important to share when I can whether that’s in my [Instagram] Stories, or directly on my feed, and doing performances.”

But like many Garinagu, food also plays an important role in her life. Dishes call for ingredients like green and ripe plantains, green bananas, coconut milk, a selection of seafood, fish – many recipes include king fish with red snapper as an alternative – and cassava, among other staples.

Hudutu, also known as machuca, is a Garifuna must-have made with fish/seafood soup and green and ripe mashed plantains. Similar to West African fufu, hudutu is served in a ball of mashed plátanos that are pounded in a hanaonce they’re cool. Family members share it alongside coconut soup with fish and/or seafood known as falmo. It can also be served with sopa de pescado, duno in Garifuna, as well as chicken soup. Falmo is a favorite for most, but Garinagu have made adaptations based on availability of ingredients, however, one thing is for sure: Hudutu brings families together.

“I associate hudutu with family and laughter,” shares Soliz-Rey, whose family meets up every Sunday. “We don’t cook it every Sunday but pretty much every time [my mother] has cooked it, it’s been on a Sunday.”

A seafood lover herself, she enjoys hudutu with all types of seafood but preferably king fish, conch, shrimp, and crab.

For communications professional Sandra Garcia Lowery, hudutu and many of the other coconut-rich foods that are a part of Garifuna culture aren’t just home in New York, they’re also home in Honduras.

“I associate a lot of dishes with coconut,” says Garcia Lowery, who was born in La Ceiba, Honduras. “That’s because in Honduras our house in San Antonio is right across from the beach, so I associate everything with that tropical-like feel; just that tropical kind of idea of being in Honduras. Because the coconut trees are literally right across the street from us, we’d just go to the beach, get a coconut, open it up and we’d use the coconut milk for everything.”

Early memories include her mother baking fresh pan de coco and resanbinsi (rice and beans with coconut milk), and another favorite: durudia (tortillas or tortillas de harina). The latter is often associated with Mexican cuisine but is native to Central America and have naturally found their way onto Garifuna tables. There is one main difference, though. Garinagu are known to add coconut milk to their tortillas, and they’re thicker, fluffier and less stretchy than other recipes.

A smile comes over her face as she recalls her mother patting the dough: “My mom used to always make tortillas for us in the morning and that was our breakfast with mashed beans [and crema].”

Part of the beauty of Garifuna culture is that even in other Central American countries, these traditions remain the same. Evelyn Alvarez is a Brooklyn native whose parents hail from Guatemala. Her mother is from Puerto Barrios and her father from Livingston. From her mom, she learned a vital lesson about food. “You have to respect the food,” says Alvarez, repeating her mother’s words. “Food is love. You have to do it with affection or you don’t do it.”

She learned this as a middle school student when her mother asked Alvarez to make rice. She made it de mala gana and accidently burned the rice. Instead of a chancletazo, her mother explained why it’s important to put yourself in the cooking process – a lesson that remains imprinted in her mind today.

“It was something that has stuck with me since, like I feel like I cook with a lot of affection,” she says. “I really want people that I’m cooking for to really enjoy.”

A mother, doula, and founder of Prom King, a nonprofit that provides dress clothing to young men, Alvarez has her hands full but is passing the traditions on, including within her own home to her 13-year-old son. “The last time I took my son to Guatemala, he was constantly eating pan de coco. He kept saying ‘it’s not the same’ [as in the US].”

Similarly, she’s made sure to make the most of her trips back home, where she indulges in her favorite foods, including fried fish, fritas de guineo, rice and beans, curtido, bocadillos, and casabe (known as ereba in Garifuna).

Ereba, a cracker-thin bread made of yuca (cassava), is a woman-led creation. In recent years, it’s become commercialized and packaged at mass, but ereba making in its truest form consists of various steps, requiring women to come together to assist in the multi-day process, particularly during the peeling and grinding phases. Once the cassava is gathered from the fields, it’s peeled, washed, ground, strained, and baked. A product of straining, the cassava flour is spread into a circle on a large hot stove, smoothed and flattened with a wooden slab with excess flour being swept away with a small, hand-held broom. This process alone takes hours and it’s not until the next day that the ereba is stored and often divvied up among family and the larger community. For Garinagu miles away from home, it’s something to look forward to when family members bring suitcases or boxes filled with ereba.

“I love my casabe with cheese,” says Garcia Lowery, who lists Honduran cheese as a favorite. “My process is I like the casabe dry and crispy, or you wet it a little bit and then you roll the cheese up inside of it.” She requests cheese from Honduras – “the saltier, the better,” she says – each time her father goes back home, and he obliges.

Although she came to the United States at a young age, spending her formative years in New York City, the millennial marketing maven has a renewed sense to invest in preserving Garifuna culture. “We can do our part of preserving culture by spending more time, while we have it, with our parents and our grandparents – those of us who are lucky to have them. Just soak up those stories so we can pass them along, but not just stories also foods.”

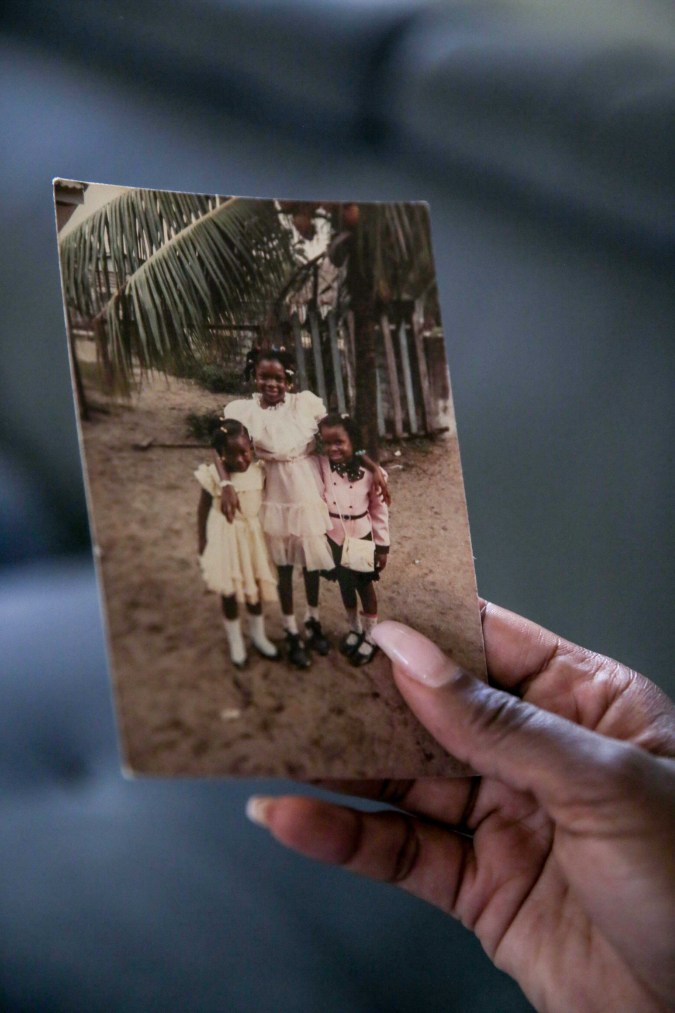

Garcia Lowery has turned a binder with blank pages into a recipe book. She’s filling it with Garifuna recipes from her mother. Similar to baking ereba – that is, the distance affects the end result – she’s had to adapt the recipes because of her current surroundings. But as she builds a written record for future generations of her family, she can’t help but look to the past. “Like my grandmother, I still remember her when I was younger going off to the mountains and coming back with stuff on her head, bringing it down and me being a little girl wanting to carry things on my head down the mountain, too,” she laughs. “Trying not to fall ‘cause it was very steep.”

Garifuna dishes are mainly found within the homes of those from the culture. But as more immigrate to the states, it’s become a source of revenue so it’s not uncommon to purchase certain items from family friends or even a restaurant. Soliz-Rey enjoys baleadas, a Honduran dish made with flour tortillas and refried red beans. It’s customizable enough that you can add an array of ingredients.

“It’s something I pretty much make I would say at least every other weekend at home, so I love to have my baleadas. And if I can’t on the weekends, I might just buy it. There’s a few, not many, restaurants I go to that I’ll pick it up and sometimes, I’ll take it to rehearsal.”

As her mom has passed on dance and food – among other cultural practices – to her, the entrepreneur will instill the same in her future descendants.

“For me, it’s very important that I pass on everything that my mom did for me to my children because I’ve seen, I’ve felt first-hand how much it’s helped me in everything,” she affirms. “Just how I move, how I talk, how I feel about myself because I know myself.”

Some say that Garifuna culture is fading away with each generation, however, that narrative is simply untrue. Things have undoubtedly changed due to migration, modernization, displacement, and access to resources, to name a few things, but if history serves as a blueprint, the Garinagu will not only survive but progress – even if it’s through cuisine, one recipe at a time.