You can read this text in Spanish here.

The oppression of the African diaspora, and consequently, our liberation, is deeply linked to the “State-Nation” concept—a form of political organization based on a limited territory, more or less constant population, and a government that ensures sovereignty.

In Latin America, the idea of a State-Nation was introduced as an “alternative” way to deal with colonialism. Since its inception in the mid-1800s, institutions that were part of this new order helped to sustain systems such as white supremacy and patriarchy by implementing laws and affirmative actions that were not meant to guarantee equal rights for all. Therefore, instead of dismantling colonial ideals that served to justify the exploitation of certain bodies and territories, the then newly formed State-Nation idea reinforced the imaginary distance between who is worthy of, and gets access to, dignified life and who doesn’t.

One of the most common affirmative actions tied to reinforce supremacy culture in South American territories, were the “whitening strategies“, as they’re called by many Afro-diaspora activists.

Argentina is one of the countries where the social and political whitening strategies “succeeded” the most. Even now, a lot of Argentinians take pride in being part of a country that is known by many as the most European-like in South America. Some, even dare to say or imply that there are no Black people in Argentina.

“The whitening strategies promoted by the Argentine State began in 1845 when the Afro-descendant community was still numerous and active”, Afro-Argentine academic and human rights activist Miriam Gomes tells us, “they had various newspapers that circulated within the community and they were present in all social structures: militia, politics, literature, etc. Still, former President Domingo Faustino Sarmiento stated that Black people were ‘disappearing’ in Argentina and that if someone wanted ‘to see one’, they would have to go to Brazil.”

It was with this racist and genocidal comment that Sarmiento inaugurated the unofficial State whitening project in Argentina. Then, whitening efforts were institutionalized through the removal of the contributions of Black people in history books, introduction of the term “brunette”/”trigueñe” as a race marker and the elimination of the “Black” as a way to identify in national censuses. The latter of which had a direct effect on public policies and budget for over a century. Furthermore, the government promoted bonuses and giveaways to incentivize European migration while enslaved people were required to pay for their freedom.

“Whitening is the first strategy of the colony, an institution that is still in force throughout the nation-states. In Argentina, especially in Buenos Aires their goal was achieved,” Luanda, a young Afro-Argentine artist, says. “They won, and they win all the time. The prevailing social imaginary is that we are ‘the Paris of America.’ That statement weighs on our bodies. Wherever we go or exist, we will be affected by this: To be recognized as non-citizens in our territory.”

Despite several attempts to erase Black folks’ contributions and existence, resistance persisted. “Black communities will never give up organizing,” Gomes says. “Actions, such as syncretism in their artistic-religious manifestations and the creation of organizations called ‘Nations’ that since the beginning of the 19th century worked to rescue the African ancestry of people and buy the freedom of its members, are proof of this. Subsequently, mutual aid societies emerged…” Since then, the Afro-Argentine resistance has continued to gather wins such as the restoration of statistical recognition of the African and Afro-descendant population in 2010.

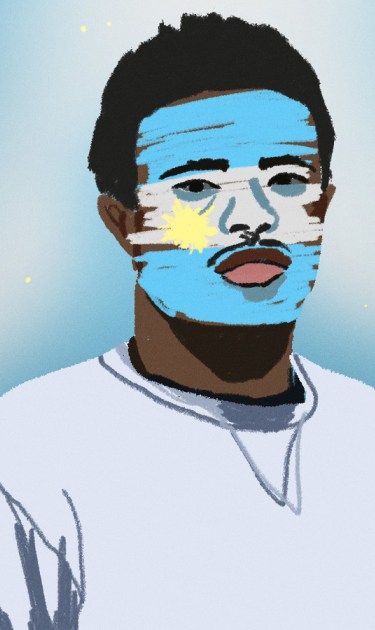

Clearly, Afro-Argentines continue to shake things up. “De ak-a,” an Afro-Argentine song at the top of our playlist, says in Spanish: “They expel me, they deny me the possibility of being. I do not want to belong, but it hurts. They look and look, and assume. My curlers they want to touch and begin to question. Where is your dad from, where is your mom from. They [the State] suppressed us from the story and it is no coincidence.”Luanda, who’s also the author of this anti-racist song, adds: “As a Black, fat non-binary person, my resistance is to live. I live and rap telling my story to embrace and reconnect with my community. I learn from them, and try to unlearn the [mindset] that is inserted in me every day. My resistance is to stand up through afro-trap, which is the fusion of trap and ancestral rhythms by us, for us.”

Recognizing the challenges and work of Afro-descendants in different diaspora communities around the globe is vital. When we build strong communities, we can fight oppression, heal and regain joy as well as trust in ourselves and our surroundings.

It’s also important to recognize the role of women and queer people in this movement which, in Gomes’ words, is a decades-long struggle that our ancestors began, now continued by current generations. May these words keep our hearts united and strong.