Like most revolutions, the one Mexico fought at the beginning of the 20th century was brutal. Over a million people, both civilian and revolutionaries alike, died in the span of ten years. And although, by its end, a new constitution guaranteeing indigenous civil rights was enacted, life was still no better: assassination, disease, and violence left the Mexican state nearly ruined.

Yet even the bloodiest revolution has its icons. Mexico’s quintessential revolutionaries, Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, have become so recognizable today that it’s easy to take their politics at face-value and romanticize what they fought for. Jason Oliver Chang, an assistant professor at the University of Connecticut, wants to change that. Speaking in late May at the Museum of Chinese in America, he gave a lecture prepared from his most recently published book, Chino: Anti-Chinese Racism in Mexico, 1880-1940.

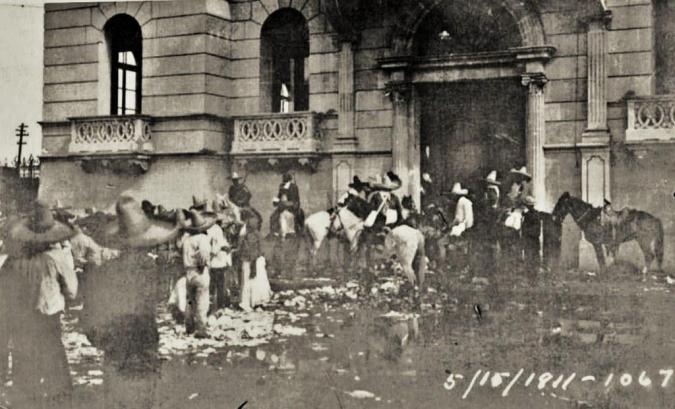

Uncovering the forgotten history of anti-Chinese propaganda and violence documented in the years around the revolution, the book reads like a dossier of state secrets. In one chilling example, you’ll read how Pancho Villa gave orders to execute 60 Chinese prisoners by throwing them down a mineshaft. Magonistas, along with many other revolutionary parties on the left and right, used antichinismo — anti-Chinese rhetoric and policy making — to popularize their own movements. But those incidents pale in comparison to the massacre that occurred in Torreón, Coahuila, during one of the first battles of the revolution. There, 303 Chinese men, women, and children were killed — some even butchered — by both civilians and soldiers, marking the bloodiest incident of anti-Chinese violence ever recorded in the Americas.

Chang, who spent the past ten years researching his book, argues that not only are revolutionaries like Villa implicated in racist, propagandistic bullshit – so is the Mexican state established after the revolution and by extension so too, as he calls it, the state-sponsored nationalistic identity of Mestizo. To Chang, Mestizo identity of the 1920s and 30s was nothing more than colonial leftovers from Spanish rule. It centered white Europeans while ignoring the basic social fabric of Mexico (an argument, incidentally, also advanced by the Afro-Mexican activists who pushed for recognition on Mexico’s national census). What better way, then, to integrate a rebellious indigenous community than establishing a collective identity made in opposition to Mexico’s Chinese? As Mexico’s ultimate Other, the Chinese were easy targets.

After his lecture, Chang and I spoke at a Thai restaurant in Chinatown to further discuss his book and talk about its implications. The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Would you say that antichinismo tarnishes the origin of the Mexican revolution?

It’s an important parable that exposes the ways revolutionary states can undermine democratic principles.

Yes, it does. But there are always many stories to tell, and the formation of the Mexican state is probably one of the most complex and well-studied areas of academia. What I say about Mexico doesn’t make other people wrong, but it’s also a story not told before. But I wouldn’t say that antichinismo is the sole origin of the revolution or Mestizo identity. In the book, I mention that there were other political organizations and revolutionaries at that time talking about Mestizos that didn’t bring up anti-Chinese discourse. There are parallel lines to the revolution’s origin, and they all poured into the same bucket, but one stream has been overlooked, and it’s this one.

Why has this history been overlooked? Does it discount those other histories?

It’s overlooked in part because it’s not an uplifting story of unity. But it doesn’t discount those other histories. It’s an important parable about the Mexican revolutionary state that can, I hope, drive some critical inquiry into other ways revolutionary states can undermine democratic principles and how this one served to strip indigenous people of rights that they had been fighting for. For instance, Mexico’s revolutionary state was successful in getting a diverse indigenous population to fall in line with its institutions. By the 1920s, most people wouldn’t identify as indigenous because that was a problematic identity.

How did that happen? How was antichinismo involved?

Indigenous people are indigenous no matter what the state says. But indigeneity was often used as a way of identifying a lifestyle or a particular culture or something that was counter to the nation. In order for a Mexican nationalism to be successful it had to be relevant to people’s lives. By the 1920s, people on the ground were still not seeing the benefits of the revolution. Life was still fucking hard. The government was collapsed. In some respects, I think anti-Chinese politics became an elitist strategy for making the state, the government, relevant to people’s lives, especially when the state couldn’t offer anything else.

Racism is most effective when non-whites practice it against each other. It becomes a part of their own subjugation.

The Chinese were scapegoats.

Right, the government can’t make jobs for you, won’t bring roads to you, won’t bring water to neighborhood, but it could get these damn Chinese out of here. In that respect, I think they thought they would get attention from these jefes if they say, “Hey, the Chinese are ruining our businesses.” That’s strategic. They’re not paying attention to anything else, but if I say the Chinese are after us and destroying our communities, and they’re taking our women, so we need to segregate them, and then we need to get them out of here, then suddenly you’re getting people’s attention. Having people go for this is a practice of institutional engagement. The people are not raising up arms. Politicians don’t want people to protest and take over capitals and legislatures and execute heads of state. They want law and order. They want people participating with the state’s institutions. So if you come to them with a grievance, they will honor that grievance. So it’s better to do that than the alternative, which was a further breakdown of legitimate authority.

Was propaganda at the root of Mestizo identity? Was it used to suppress indigenous identity?

Yes, racism is most effective when non-whites practice it against each other. It becomes a part of their own subjugation. That’s the core of what I wanted to show. I didn’t want to write just about the Chinese being persecuted. Antichinismo fucked up Mexican people too. Fucked them up hard. And that’s the tragedy of it: no one won. No one gained from this. It was bad for everyone.

Identities are fluid and different sets of exclusionary ideologies serve political purposes.

What should Latinos, especially those who identify as Xicano, take away from that?

What I hope is revealed is the methods and ways states manipulate people and to see that identities are fluid and that different sets of exclusionary ideologies serve political purposes. So, what I mean is, it doesn’t have to be antichinismo. It could be patriarchy. It could be homophobia. Those are things that hurt Mexican-Americans, hurt Chicanos. But it’s still something that is practiced. So in the same way that antichinismo did not serve Mexicans, homophobia doesn’t serve them either.

What do you think Chinese-Mexicans and Chinese-Americans can take away from this history?

I hope they will read it and identify with the variety of political contexts that Chinese entered. For Chinese-Mexicans, I hope they will find some explanation for their family history. Some people came up to me after the lecture and said this explains my dad. This explains my mom. This is a story that has been denied to them by the state, the nation, by their community. For some it will feel like an a-ha moment. For Chinese-Americans, I hope they consider that the struggle, if they identify with political struggle at all, extends beyond fighting for one’s own rights. Rights-based political movements should stand up for other people’s rights too.