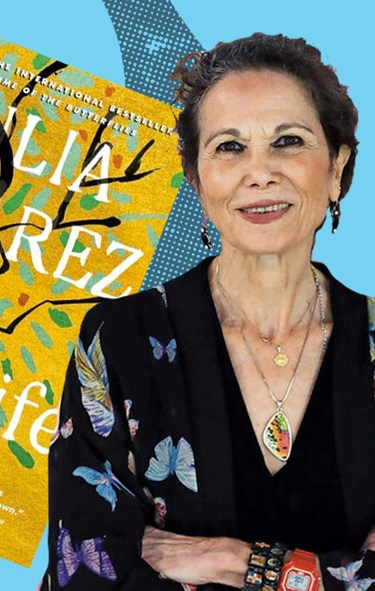

Julia Alvarez recently released her first adult novel in fifteen years. This time, the beloved author of How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents and In the Time of Butterflies takes on the themes of aging and death.

In Afterlife, a recently widowed, elderly Dominican-American writer named Antonia is pulled into a moral predicament about whether to help an undocumented migrant worker and his girlfriend. At the same time, Antonia must manage another crisis; she and her sisters are trying to locate her adult sister Izzy who seems to have gone missing. Though the novel revisits some familiar territory—specifically sisterhood and life as an immigrant in the United States—the voice and approach are different from Alvarez’s earlier work. For example, Antonia is constantly questioning herself and testing the claims she made only minutes earlier at the beginning of a paragraph on immigration, death, or privilege.

The tone is also marked by a great deal of sorrow and loss. After trying to find their missing sister, Antonia and her sister Tilly head to a motel where they turn on the television set before falling asleep. Alvarez writes, “It’s a habit Antonia has become well-acquainted with in her empty house—turning on the news, in her case the radio—for company, her own sadness put in perspective by the larger sadness of the world.” There’s the Christ Church Massacre, for example, and the loss of her husband, whose arguments and idiosyncratic sayings she rehearses in her head. In another passage, Antonia teases Tilly about her eccentric husband.

“‘He’s never left me… He’s not violent. He likes my cooking.’” Tilly would say. “The description left Antonia feeling sad,” Alvarez writes.“The great loves they had all dreamed about as young women reduced to the dubious compliment of horrors averted…” This type of sorrow and disappointment echoes throughout most of the book.

As always, Alvarez’s portrayal of sisterhood shines on the page offering brief respite from the grief that often overwhelms Antonia. Perhaps the most distinctive aspect of this novel though, is the way in which Alvarez tackles the privilege of citizenship. Though Antonia is an immigrant, Alvarez makes sure to emphasize that she does not face the same struggles or challenges as Mario and Estela (the couple she’s faced with the potential of helping), highlighting an important conversation in Latino communities about how undocumented Latinos are especially vulnerable. Unfortunately, Alvarez’s depictions of her undocumented characters feel thin and one dimensional at times, as if the characters were only there to serve the plot and help Antonia face questions about privilege and moral responsibility.

To Alvarez’s credit, she also seems to be questioning herself throughout the book. Repeatedly, Antonia mentions a novel she wants to write about immigration and “invisibility.” But the voice of her dead husband Sam haunts and challenges her from beyond the grave: “Invisible to whom?” Later, she forces Mario to take back his girlfriend after he discovers she is pregnant with another man’s child and we see Antonia’s own ugliness float to the surface.

“Antonia does not have time to indulge agency, rights, agreements. She is the one with the power to say how their story will go. She does not return his gaze. She has rendered him invisible, like everyone else,” Alvarez writes. “Not something she would want to fess up to in that book of hers.”

It’s dangerous to conflate authors with their characters, but as a reader, I could not help but wonder if this passage was a way for Alvarez to hold herself accountable.

Ultimately, Sam is the character who Antonia best makes visible with her words and memories, even though he is dead. In a way then, Afterlife fits into a very old tradition of the writer’s artistic resistance against death.

“What if anything does it mean? An afterlife?” Alvarez asks. “All she has come up with is that the only way not to let the people she loves die forever is to embody what she loved about them.”