Throughout his adolescence, my father was “Other” on paper. “I was not white like a Mennonite; not Black or Asian,” he explains. “I always felt like I was giving a wrong answer.”

When my father made it to Los Angeles during the first wave of Central American migration in the 1980s, the Census Bureau had just implemented a new demographic option to check off: Hispanic. A decade prior, the government began asking citizens their origins by adding a limited number of Latin American and Caribbean national backgrounds, such as Mexican and Puerto Rican, as racial categories. Forty years before that, people of all Latin American descent were deemed “Mexican” by officials.

Latin American activists in the U.S. helped the creation of the term “Hispanic.” It came as a response to the government pigeonholing all non-Black minorities as white. In the 1930 census records, for example, “Mexicans, Indians, Chinese and Japanese” were recorded as “foreign-born white families.”

But, as the activists witnessed, the inevitable othering was visible – from the ethnic slurs emblazoned on doors to bar entry to the gaps of poverty level compared to European-Americans. Hispanic was an imperfect, surface-level solution, agreed on by some activists and bureaucrats, that tried to bond together Spanish-speaking communities in the United States.

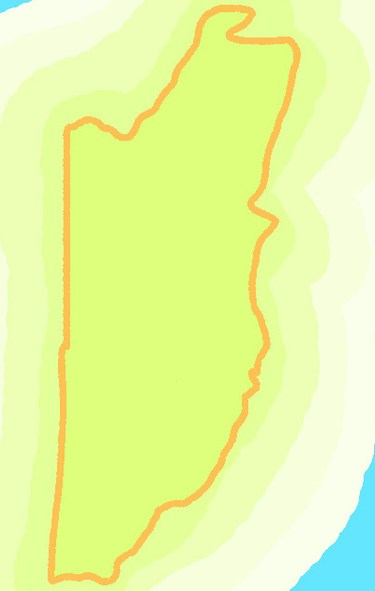

In Belize, my father was a mestizo or, as English-speaking locals commonly identified him, a “Spanish” due to his non-anglo last name and his caregivers’ fluency in the language. He grew up in a Catholic home in Corozal, a small Spanish-speaking town south of Chetumal, where his grandmother’s cooking reflected the ingredients of the Yucatan peninsula – habanero, recado and banana leaves – and his grandfather’s vinyl player spun the records of Mexico’s finest musicians. “At home, it was Spanish; in the classroom, it was English; and in the playground, it was Kriol,” my father says.

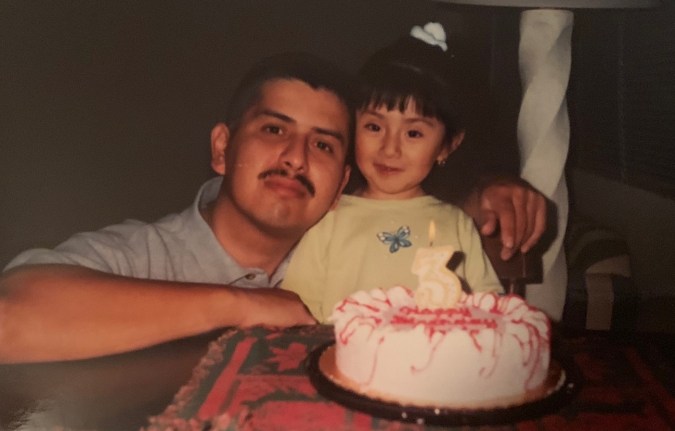

Settling into South Central and later Inglewood, my father’s indecipherable accent – a mix of Caribbean and Spanish – alienated him. As the years passed, the island in my father’s broken tongue began to fade, and he soon adapted to Mexican slang and culture – the closest thing to Corozal. “I had to,” he adds. “A lot of my friends, the people I resonated closest with, were Mexican.” My father found a community as he navigated a new country through the bond of a connected struggle of the south-of-the-border diasporas “Hispanic” – and eventually “Latino” – had promised.

“Hispanic was the closest thing I related to, but still it felt like I was fake.”

Moving away from the mid and late 20th century, Latino has become a more prominent ethnonym, and as of the Internet age, Latinx as well. “Hispanic” was and is imperfect and, to most, was a softer way to say “from Spain” – an erasure and perhaps even a glamorization of Latin America’s grueling history of colonialism. Additionally, the emphasis of Spain and the Spanish language have isolated diaspora communities from countries such as Brazil, Haiti and Belize – and thus an identity dilemma and interrogation begins for my father, for me and for many other Belizeans. “Hispanic was the closest thing I related to, but still it felt like I was fake,” my father reminiscences.

The official language of Belize is English. After centuries of disputes between Spain, England conquered Belize, then known as British Honduras, as one of its colonies in 1862. Over the course of slavery and wars of the bordering lands, the four main ethnic groups were formed: the Creoles, the Mestizos, the Mayas and the Garifuna. “[The four ethnic groups] are all diverse in culture and in physicality,” says Victor Manuel Durán, a Mestizo-Maya Belizean and editor of An Anthology of Belizean Literature, a collection of works by Belizean writers in the country’s four prominent languages: English, Kriol, Spanish and Garifuna.

For Durán, his arrival in the United States in 1980 never impacted his view of his identity. “I already knew my ethnic and racial background, and moreover, was very proud of it and still am,” he says.

Although his transition to another country didn’t adjust his labels, Durán recognizes the dissimilarity of U.S and Belizean ethnic politics. “Compared to Belize, it is more difficult in the USA to carve your racial and ethnic identity since, in [the United States], there is a clear separation between races: You are either white or of color,” he says. This is a reality that prompted a term like “Hispanic” to be pushed for and conceived to begin with.

“The word Latino encompasses a culture; to be Latino is to embrace and be part of a culture,” says Durán, who is also a professor of Spanish and chair of the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at the University of South Carolina, Aiken. “Latinos can be racially white, Black, Indian, mixed; [In Belize, within its four main ethnic groups,] the Latinos live in the North and in the West and practice ‘Latino culture,’ especially in the areas of foods and family values.”

As “Latino” becomes more embraced as the preferred ethnonym, distinct words such as Afro-Latino and Latinx help to expand what Latino means as a culture and a way to dismantle any colonial or racist attachments to it. As Durán states, being Latino includes all races (a concept confusing to many) and the struggle to find a home in Latinidad doesn’t stop or even start with being mestizo.

“Latinidad can be a community when being ‘Other’ gets lonely.”

“I do see a lot of Latinx- and Afro-Latinx-identifying Belizeans, which I think is great as we leave, or try to leave, British colonial sentiments,” says Katie Numi Usher, a Garifuna and Kriol Belizean artist and writer based in a Belizean village called Ladyville. Although Usher is unsettled about the Latinx label for herself, she acknowledges the unique Belizean struggle of being “Caribbean and Central American culturally and geographically positioned, while still oftentimes excluded from discussions of either region.”

Latinidad can be problematic. Usher elaborates some of the issues of Afro-Latinidad, including “appropriation and erasure or only meaning Latinxs who are mixed-race.” But she stays optimistic: “This can be a time to clarify and reflect on [what it means to be Latino/Latinx].” Latinidad can be a community when being “Other” gets lonely.

As my father further developed his place in the United States, he became more comfortable with identifying as Hispanic, and later sometimes Latino, on paper and in statements. Growing up with a Latino Mestizo father and a Chinese-Belizean mother in an English, Kriol and Spanish-speaking household, I have felt othered, too, and I continue to question where my community is. Belize is a multicultural country, much like the United States, but 428 times smaller in size. When one migrates, it can feel much like an optical illusion of endless diasporas and history where one belongs everywhere and nowhere. But perhaps, the othering of Belizeans is what qualifies us a spot in Latinidad after all – if we choose to take it.