As the United States sees a major swell in the removal of its confederate monuments and flags, the country’s oldest colony, Puerto Rico, has yet to undergo its own transformation. Tributes to colonization—sculptures, public plazas, and even roads that pay homage to Christopher Colombus and Juan Ponce de León, for example—remain mostly untouched, save for some anti-imperialist graffiti here or there, throughout the island.

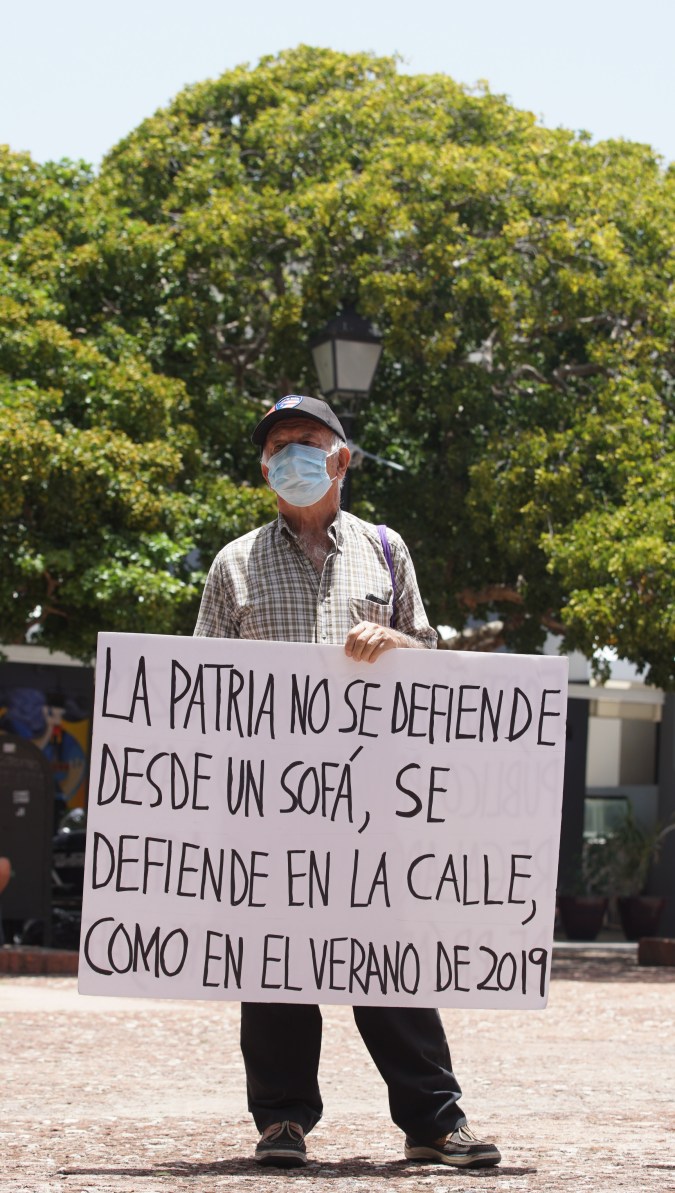

The removal of these monuments and other tokens of colonization have long been the focus of resistance groups in Puerto Rico. But in the current international sociopolitical climate, the call is reinvigorated.

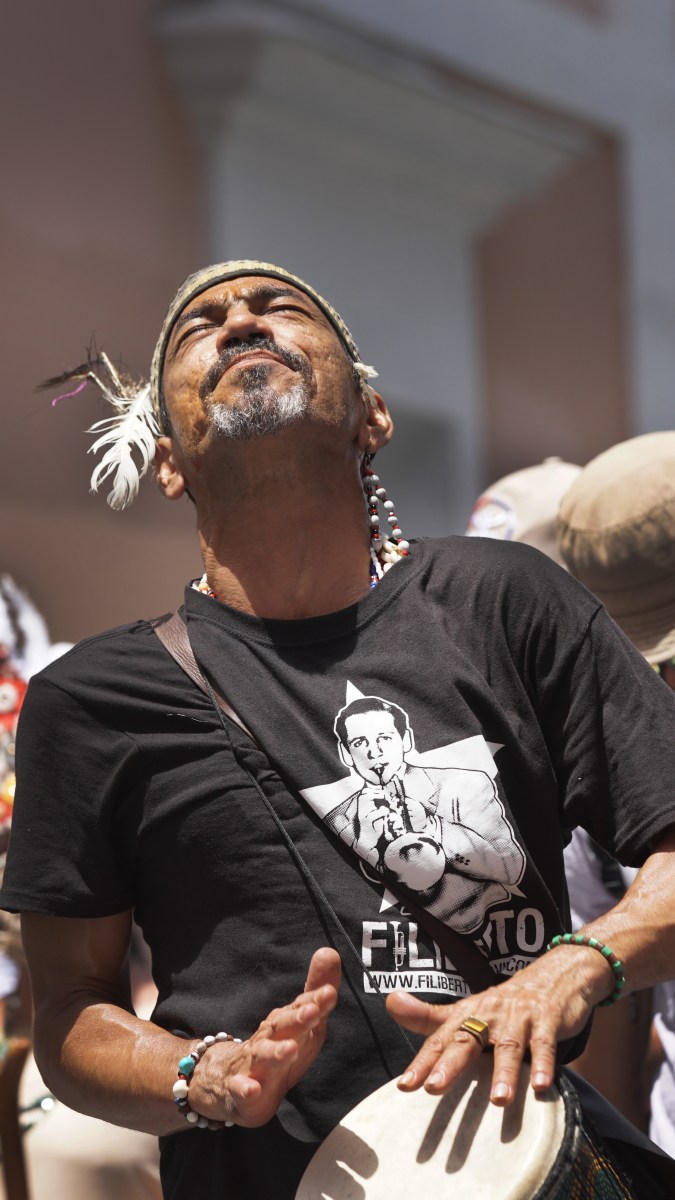

On July 11, the Consejo por la Defensa de los Derechos Indígenas de Borikén (Collective in Defense of Indigenous Rights of Borikén) organized an Areyto Nacional, a gathering to demonstrate opposition of the statues and colonialism in general, in Old San Juan. The event began at the Capitol Building and included a march to the statues of Christopher Colombus (Plaza Colón) as well as that of Juan Ponce de León (Plaza San Jose)—where the areyto, a ceremonial tradition of native cultures including the indigenous Taínos, Canjibaros and Arawacos of Borikén was performed.

“There have been a lot of luchas here,” says Pluma Barbara, an Indigenous Can Xibara of Boriké. “The difference now is that las luchas are being fought through alliances and in solidarity.”

Barbara is a longtime activist for Indigenous rights in Puerto Rico and a member of El Consejo por la Defensa de los Derechos Indígenas de Borikén which is comprised of various Indigenous groups based throughout Puerto Rico including Movimiento Jíbaro Boricua, Tribu Kan Xíbalo Caniba Tun, Hermandad Taína, Organización CAN and many more.

Support within the large crowd of attendees also came from members of the political resistance group Jornada: Se Acabaron Las Promesas, as well as Afro-Caribbean activists who denounce the slavery and exploitation that made colonization possible.

In addition to the ceremony, the Consejo por la Defensa de los Derechos Indígenas de Borikén delivered a resolution in regards to the removals to San Juan Mayor Carmen Yulín and Puerto Rico Governor Wanda Vázquez. The collective has also drafted and submitted proposed law to be considered by the San Juan Municipal Assembly.

“It was interesting to watch the patience of their ritual and ceremony,” says Zulma Oliveras Vega, a Two-Spirit and queer human rights advocate in Puerto Rico. “While still claiming that they’re tired of these statues of these people who represent genocide, they’re politely asking to remove them.”

Oliveras Vega comes from a more militant activist background but expressed the utmost respect for the collective’s peaceful process.

This approach has, to some extent, worked in the past. Pluma Barbara notes that the enormous Christopher Colombus statue in Arecibo (on the west coast of the island) was not originally intended for that municipality. Standing taller than the Statue of Liberty at more than 350 feet high, the monument was rejected throughout the U.S. Its creator offered it to Puerto Rico by way of Cataño, then Mayaguez, but both pueblos rejected its installation—in part as a result of the opposition of Indigenous activists, Barbara explains. It was finally erected in Arecibo in 2016 with the approval of Mayor Carlos Molina, a member of the conservative New Progressives Party, who remains the municipality’s mayor today.

For Barbara, these colonial statues perpetuate the acceptance of colonial genocide, violence, looting and pillaging, and sexual violence against girls and women. “These figures represent the worst crimes of humanity,” she says.

They also represent lies—one of them being that Indigenous Puerto Ricans no longer exist thanks to the false-spread idea that they were entirely eradicated through colonization.

“They want to say we are extinct,” Barbara says, “because if you extinguish un pueblo, then there isn’t a pueblo to defend its rights to the land, political participation, economic structure, social structure, education and reparations. (On the latter, Barbara says what is owed by the U.S. to Indigenous and Afro-Caribbeans is at least triple Puerto Rico’s public debt of more than $70 billion, and the same goes for Spain.)

The colonialist revisioning of history—which is what is taught, with few exceptions, in Puerto Rico’s public and private schools—also implies that the Indigenous population is a homogeneous one.

“We are similar but not necessarily the same,” Barbara says. “We don’t do the areyto the same way, or wear the same clothes, we don’t all play the same rhythms of music.”

The Indigenous community also includes el pueblo Jíbaro, descendants of Mayas Kan’ Xibalo, the Taíno Guatu-Ma-cu-A Borikén, and others.

If diplomacy fails, however, there are other groups, Barbara and Oliveras Vega both note, that are interested in addressing the problem of the colonial monuments by other means.

“[Colonialism] taught us to just feel helpless and accept that this is what it is for us,” Oliveras Vega says. “I’m tired of that kind of thought.”

Removing the statues would be a step in reclaiming history—and, Oliveras Vega hopes, unlearning all that colonization wrought, from racism and colorism to homophobia and the rigidity of the gender binary. None of this will be easy, but for both Oliveras Vega and Barbara, it is absolutely necessary.

“The biggest crime, for me, in history, is the crime of colonial invasion and colonization,” Barbara asserts. “It eliminates identity, takes away your language, your religion, your family structure, your economic structure, everything that represents you. It’s the greatest crime—and that’s why there’s a resistance to admitting that Indigenous people of Boriken and the Caribbean exist.”