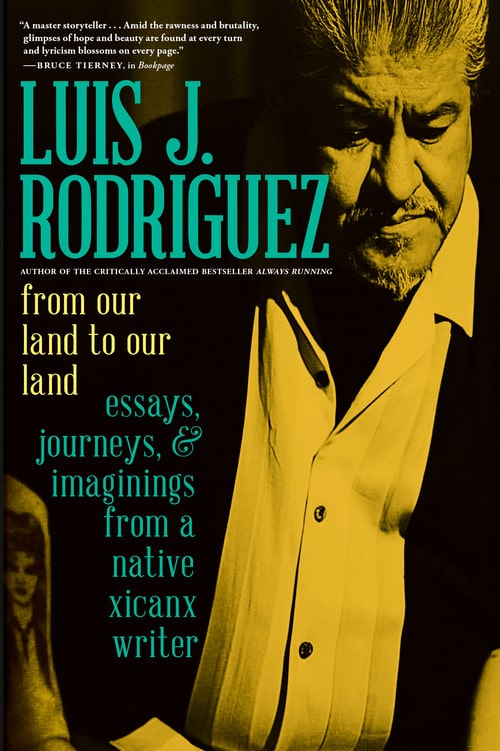

Luis Rodriguez’s collection of essays From Our Land to Our Land: Essays, Journeys, and Imaginings From a Native Xicanx Writer does not begin with his own words but rather those of a reader he overheard speaking about his 2003 short story collection The Republic of East LA: “You teach Mexicans a little English and now they think they can write books.” His latest book, slated to release on January 28, 2020, is a response to that comment.

The collection itself feels like a type of ars poetica. It is one writer’s reckoning with xenophobia and racism in the United States, but it is also a reflection of his relationship with language and how it has been shaped by activism, faith, pop culture and identity throughout the last four decades. By doing so, he explores the writer’s role in a world increasingly marked by racial violence and natural disaster.

Rodriguez is most known for his 1993 memoir Always Running: La Vida Loca, a reflection on his life growing up in the ‘70s surrounded by gang culture in East Los Angeles. These essays feel like a natural extension of that memoir. He writes about teaching in prisons, his work as a poet laureate and the violent racism he continues to experience despite his accolades.

He also writes about the examples of violent racism he experienced, for example, while in elementary school. In one brilliant passage, he shows how that brutality first taught him the power of language: “On my first day, I went from classroom to classroom because I couldn’t speak English and teachers didn’t want me among their students. A teacher finally let me stay, but she had me in a corner playing with building blocks most of the year. I’d pee in my pants since I didn’t know how to say I had to go to the restroom. Whenever a Spanish word left my mouth, I was punished, including being swatted by the school’s principal. I made the mistake one day of stepping into the kindergarten class my sister was in so I could pick her up. The teacher slapped me across the face in front of everyone.”

Throughout the collection, Rodriguez returns to one question: How, as writers, can we harness the power of language in order to heal? In Remezcla’s interview with the esteemed author and poet, he explains, “every time there’s a racist person, it challenges all of us to find the language to speak out and insist that we all belong.”

Here, Rodriguez talks about poetry as a radical healing act, the rasquache — a Nahuatl word meaning “creativity out of disorder” — writing style and reconnecting with earth, among much more.

In these essays, you often circle back to the argument that part of the reason why humanity is in crisis is because of our severed relationship with the earth. As a writer, how do you seek to address the anthropocene?

I think what’s important to point out is that we need to get back to some very strong alignments that we’ve lost as a “civilization,” and that is the language with nature. I mention it in my book. We’re disconnected. We’re taking too much from the earth. We’re poisoning the earth, water and land. We also have to have a connection with our own natures, the gift and beauty that people can bring into the world.

You mentioned that as poet laureate, you want to make poetry a radical and healing act. What do you think makes this artistic form apt for healing or inspiring change?

What I like about poetry is that the shape of the poem is totally based on its content. I call it the language with the deepest capacity for soul talk, where you really get into something deeper within everyone. You’re not just talking from the head, even though there’s poetry that does that. You know, with poetry you can speak from any place you want, but it gets you to a [further] depth than other forms of language or expression do.

You speak of poetry’s unique way of escaping the trappings of capitalism because it is not easily monetized. There’s an interesting anecdote that you share where you describe you and famed Mexican-American author Sandra Cisneros turning down money from Nike for an ad. What advice do you have for writers trying to balance the demands of living and trying to pay rent while also writing poetry?

Wow, that’s a great question. I think it’s one of the tensions we all have as writers and poets. How far do you go? I make a living doing this, so I have to constantly look at who’s giving me the money to get there. I mean, there’s one expression that says, “all money is tainted.” The idea then is if all money is bad, then you might as well take it. But I do think there’s some direct funding that I wouldn’t want to get. I wouldn’t want to get money from the oil and fossil fuel industries and I wouldn’t want to get money from big corporations that only want to use my image or my name to sell their products. However, let’s say it’s a product I really love, and I do that. OK then, I have to accept that responsibility. Right now, I can’t imagine doing that for any product. I know that my poetry has to speak for itself, whether there’s money coming out of it or not.

As poets, most of us don’t make any money. I happen to be a little bit more successful, but I also try to do it on my terms. I don’t want to compromise my basic principles just to make a little money. I hope I’m being clear, because obviously we all need money, but people have to have integrity. I think that’s what you teach the next generation that follows: Poetry has to have some type of integrity.

In one essay, you write, “To understand the Xicanx soul, which still claims facets of the Mexican soul, you have to understand rasquache.” You write that the term “originally from the Nahuatl language, literally means ‘by the seat of your pants,’ creativity out of disorder, doing the most with little.” You talk about how that shapes the Xicanx soul. How do you see that affecting your poetry and literature?

Rasquache is a concept that says every mistake is a new style. You risk making mistakes in art, and that’s an important thing that we’ve lost. We go to schools and we are taught by the best artists, and we’re losing that very authentic, real “I’m just putting stuff out there.” Maybe it doesn’t work, but that is part of the development of the art: make mistakes, fall into a pitfall, get up and figure out what you’re doing. I wrote lots of bad poetry. I did go to school and learned some things, but I didn’t really learn in school. I learned by writing. I learned by reading, by hanging out with poets and by picking up poetry books here and there. I began to see what’s out there. There were forms I was interested in, but I had to say, “This is rasquache. I’m just doing this.” I’m not saying that working isn’t a good quality for poetry — you have to be rigorous in what you’re doing — but I don’t think it means I have to write like other people or write in any particular way. I have to be true to my heart, my voice and my soul.

There are always Latino writers that are going under the radar and getting missed. Are there folk that you are reading that you would recommend for readers of Remezcla?

I mentioned Javier Zamora, a Salvadoran writer. There’s Erika Sánchez. Right now, I’m a judge for the Kingsley and Kate Tufts poetry prize, which is a large prize for poets in the country. I have like 40 books, so I’m reading all of this amazing poetry. They’re from all over the country and their voices are so diverse. Some of them are new voices and some of them are people who have been writing for years. It’s amazing to be swimming in this sea of poetry. I just love it. I can’t tell you who they are, because they’re being judged, but I will say they are some powerful, wonderful, fantastic writers coming out, young people and older writers, too. I’m very excited about where poetry is going.