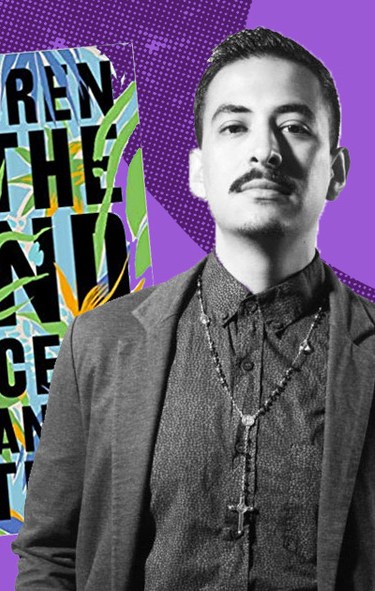

Marcelo Hernandez Castillo turns to memoir in Children of the Land in order to explore his family history and the double consciousness of living undocumented in the United States. The result is beautiful.

Hernandez Castillo is most known for his work as a poet and his award-winning 2017 collection of poetry Cenzontle. Even though his new book is written entirely in prose, Hernandez Castillo’s skills as a poet shine on the page. Whether he’s writing about traveling to Mexico to visit his father who was deported ten years ago or being interviewed for a green card, the rhythms of his sentences resonate.

Throughout the book, Hernandez Castillo shows how undocumented immigrants live in constant fear of state surveillance and reflects on philosopher Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison to argue that the wall at the Mexican-US border acts as a type of spectacle used by the state to control and terrorize the migrant.

“I ventured to believe that the function of the border wasn’t only to keep people out, at least that was not its long-term function,” he writes. “Its other purpose was to be seen, to be carried in the imaginations of migrants deep into the interior of the country, in the interior of their minds.” Later, describing an interview with the Department of Homeland Security, he writes about how the state demanded him to share even the most intimate of details in order to prove his love for his wife:

“I wasn’t certain if I knew Rubi’s body the way the law wanted me to. Had I ever spent my nights looking at the shapes of her birthmarks, wondering what they resembled?” he wrote. “I hardly even knew my own body.”

This is just one of the many moments in which Hernandez Castillo moves the reader. In a conversation with Remezcla from California, Hernandez Castillo opens up about his writing process, influences and the difficulty of constructing a memoir.

The book is written in what you call “movements” that are composed of fragments of memory and family history that shift from the past to the present day as you literally travel back to Mexico with your wife. What influenced your choice to shape the memoir this way? Was this always the narrative structure you had in mind or did you land on it during revision?

I didn’t deliver the book that I promised them, because it changed often. I was thinking it was going to be a book of essays at first. More like cultural criticism, on pop culture, on music, on borders, on surveillance. Part of that still stays there, but not in the academic essay form. As I slowly began to write it, the narrative that I was continually living with and the narrative of my family history just kept popping up more and more. I think it’s mostly because as I began to write, different memories would pop up. I was exploring the past because I hadn’t thought about it. So, the shape/structure that it took ultimately was decided because of my past as a poet. And not necessarily as a narrative poet, but one that is more lyrical.

My book is a little more experimental, a little more fragmented. So, when I went to write, I found that I couldn’t talk of the past in the same way that I could talk of the present. The long essays that take up sometimes a quarter of the book, they are all in the present and they are written in a more expository manner. In a more scenic and chronological manner, because they were more immediate, and they were fresher in my memory… and because I had lost so much of my memory. Over the years I just don’t remember so much of my childhood that what I do remember is just flashes of moments and feelings. I don’t necessarily remember the details, but I remember how I felt.

It’s interesting for me to hear that the details were something you were struggling with because I feel like there are such great details in here. There are passages that feel very much like poetry. There’s one where you talk about your mother trying to have a child: “Perhaps it wasn’t only seeds she planted but objects—a small doll, hoping for another daughter, the wingless bodies of bees she found in the courtyard, all of her children’s baby teeth she kept in a small cloth, hoping for… I don’t know what.” There’s such an attention to detail here. It’s true, memory is faulty. So, how were you able to achieve certain moments like that, when it’s hard to remember what happened when you were eight years old?

I interviewed my mother for a lot of the earlier stuff, obviously—for what happened before I was born. My mother, if she had received the opportunity to study something, I think she would have done something because it was very easy to turn what she gave me and present it in that way. It was moments like those that my mother retained.

The only memory she has of her father, my grandfather is washing his bandana when he got home from the US on one of his trips. She just told me she wishes she could remember the song and his face rather than just the tune of it. That opens up, for me, such a broad range of the potential of what there is to explore. Yes, it is a memoir, but on top of that, it’s a memoir with my commentary—kind of like the commentary that I wanted to do originally. Ok, so what are the repercussions of this? Ok, so what are the consequences of these actions? What does it mean for my mom to have forgotten her father’s face and then not see it until 30, 40 years later? And only because somebody found a little wallet-size passport photo? [When she was a child] he had been there on the wall the entire time, but they were not allowed to look at it. My grandmother was very superstitious. She wore black for a year or two, maybe even more after his death, and she turned over all of the portraits. So, my mother doesn’t remember early on what her father’s face looks like.

My mother, my grandparents, their fathers, my great grandparents have been doing kind of the same thing over and over. As I say in the book, we’ve been doing this for a hundred plus years. My great, great grandfather came in 1916, crossing through the border and getting deloused in El Paso. The rhetoric has kind of stayed the same. Yes, you know, we are not being deloused. But the rhetoric of infestation is still the same. And I feel like those sentiments are all still here and still relevant. I feel like a lot of what my mother saw and witnessed and felt is a lot of what her father did 20, 30 years before. And I always wonder will that also be my son, when he’s old? Like is this the point at which we finally just stop moving?

This memoir does not have a “traditional narrative arc.” How did you choose the arrangement of the passages? What were the different ways that you linked these memories to the present? There’s this interesting tension and overlap of the passages. It reminded me a lot of poetry.

Yeah, the thematic concerns of let’s say one of the movements juxtaposed with the subjects, thematic concerns or arguments of one of the larger sections. I rearranged the passages many times. I wrote the titles on flashcards. I would carry them around and just shuffle them around at random times and see if I could find any similarities. At first, what was it like to have the past portions going in chronological order and the present essays go in the opposite direction? Certainly, I was able to do that because I didn’t write them in order to be dependent on each other. I could move them easily around. The only things I needed to adjust here and there were: Have I already mentioned this? Or do they not know what I am talking about because I have not said this at all? So, these were just little things that I had to insert. Like, oh yeah, I can’t talk about this because they don’t know that this happened yet, because I moved it to a different section. So, I really focused on each section as a continuation of the past one, but also as a thing in and of itself.

There is such attention to detail here and control over the rhythms of the sentences. I felt like I was underlining 75 percent of the book. How do you think your background as a poet influenced how you approached memoir?

When I wrote, I talked to some of my friends who are prose writers and they delivered their manuscripts in Times New Roman, 12 point font, double spaced, with one-inch margins. I couldn’t imagine that, because it felt like such a burden on any type of creativity. So, I wrote it and printed it out with a different type of font, size 10 and then with like a four-inch margin to the right and a two-inch margin to the left, so that it would look exactly how I thought it would look in its final form in pages.

As a poet, I’m also interested in the line break and what the difference is between one pause in a line break and one pause in a stanza. It took me a long time to figure out the differences in pauses, or if I could say it better, the degree of separation. So, the degree of separation between Chapter One and Chapter Two is really big right? The degree of separation within one chapter, Section One and Section Two is still big, but not as big as that, right? And then the degree of separation within one section between the asterisks is a little bit less. And then finally the last one is probably the degree of separation between a movement that disrupts the pattern of one of the larger essays. So, I was wondering should I do all of the movements in numbers? Should I do all of the asterisks in numbers? Should nothing have numbers? Should everything be an asterisk? I certainly was very vigilant about how I divided things up, because of my obsession with pacing.

I saw references to Foucault as you characterized not only the ways in which the wall at the border is used as a spectacle to control and punish but also how undocumented immigrants navigate life knowing that they are constantly under surveillance. You also repeatedly return to the words of Wendy Xu: “I am trying to dissect the moment of my erasure.” I wondered, what and how other writers, poets or philosophers influenced your work as you wrote?

Yeah, at the pivotal time that I was starting to think of these essays—because I had stopped writing poems—I was just super depressed. My mother was leaving. And we didn’t know what would happen, how would it go down. I was still in grad school and taking a lot of theory classes. And, yes, I read a lot of philosophers for the sake of their arguments, but also through the lens of how their ideas fit into the undocumented experience. I think Foucault made the most sense for me in terms of his book, Discipline and Punish, about how punishment reverted from being on display in the public square as a form of controlling people so they could see the violence the crown was capable of committing and these ideas of surveillance that he had, where you don’t know when somebody is watching you. But you know that they could be watching at any moment. And it is that uncertainty, that one-way mirror that just really fascinated me. So Foucault, definitely. Every time I’m put on the spot to talk about the writers I really admire and really inform the book I always blank [and] later I’m like, Oh, that’s right!

But definitely, I’m not a prose writer so I had no model for how to proceed. And I think that helped me more than anything. I don’t have an MFA in creative non-fiction. I didn’t even take any creative non-fiction classes in undergrad. I don’t know the conventions. I don’t know what to do and what not to do, the taboos that a professor would tell you not to do. So, it was really difficult to write, but also really rewarding in terms of I could fail, and it was ok. I could come up with twenty pages and throw them away because I wasn’t so caught up with the first try has to be the best try as I am with a lot of poems now that I write. I’m more hesitant to write bad poetry. So that was what I kind of had to get out of.

You write, “When I came undocumented to the US, I crossed into a threshold of invisibility. Every act of living became an act of trying to remain visible. I was negotiating a simultaneous absence and presence that was begun by the act of my displacement: I am trying to dissect the moment of my erasure. I tried to remain seen for those who I desired to be seen by, and I wanted to be invisible to everyone else. Or maybe I was trying to control who remembered me and who forgot me.” This made me think so much about the process of writing a memoir and the often difficult decisions you have to make as a writer about what to withhold and what to reveal. But, also how you describe editing how you are seen in the real world to survive. Can you talk about your writing process? Were there parts of the memoir that felt challenging to write?

That was a weird contradiction I came across. For so long I have held so much back that it was almost the opposite of that, which is why, although I was not raised Catholic, I gravitated later in life—especially after I married my wife who is Catholic—towards the Catholic sentiment of confession. Because we were an evangelical household, we kept things more to ourselves because to reveal them would reveal hypocrisy. And I feel like if you’re going to do something that isn’t right, at least in Catholicism you just pay your penance and you can move on with life. But there was so much guilt instilled into my upbringing, especially with the church, that at the same time that I wanted to hide, it felt cathartic to just confess in a way that I could never do with my poetry… A lot of close people around me said I don’t think I should be reading this. It feels like I’m spying on your journal because they were there when a lot of these things were happening. Even my wife I have a difficult time talking about these things with. It’s only when I’m alone on the page that I feel I can talk about this. So, I guess my writing process was just a tornado. I kept one journal for that entire book, and I looked over it the other day. And it’s just rambling. It’s just insane. I sometimes almost don’t even remember what I wrote. It really was just tapping out and stream of consciousness until things started connecting and making sense and one thing would trigger the next.