Maggie Loredo wishes that she didn’t have to rehash the painful details of her story every time a reporter comes to Poch@ House, the Mexico City center for deportees and returnees she co-directs. As she points out, the injustices of US and Mexican economic and legal systems cannot be reduced to a single face and a single story. But Loredo has also known the loneliness that can result from staying quiet, from thinking you are the only one who’s had their life ripped in two. “It could be because of the fear,” she ventures, reflecting on the silence surrounding life after leaving the United States. “Even the undocumented community never really asks what happens when their neighbor disappears.” So, she methodically answers the same questions over and over in the hope that her words will help others facing the same difficult decisions that she once did.

When Loredo was a high school sophomore in Georgia, she discovered she was undocumented. She’d arrived in the United States with her Mexican parents at the age of two. While she was a diligent high school student, her immigration status barred her from receiving financial aid to attend college, or from entering a professional certification program. “Why do I suddenly stop having rights at the age of 18?,” she asks, remembering the emotional rollercoaster of that moment and the years that followed. “I was angry at the country, but more at the government. They were basically closing the doors on me.”

Feeling she had no other recourse, Loredo left behind her mother, father, and brother to move back to Mexico in 2008 to continue her education. “I didn’t want to do it,” she says. “But it was the only option. I wasn’t going to be able to do the things that I wanted to do.”

The process of voluntary return can be nearly as traumatic as forced migration.

The process of voluntary return can be nearly as traumatic as our standard image of forced migration. Just like deportees, returnees often leave the US when they run up against laws that bar them from advancing in life. And like deportees, once they’ve left they cannot return to see their loved ones and the only home they can remember having. Though Mexican returnees face daunting challenges upon arriving in their country of birth, there is no database that keeps track of them. Official figures are only available on people who have been detained in an ICE facility and deported (and many activists feel that even these numbers are unreliable.)

Once reunited with extended family in San Luis Potosí, Loredo found that her social and legal standing in Mexico was also in question. “I tried to hide my accent because people would ask me where I was from,” she says. “Why was I speaking perfect English, looking like a Mexican?” Adding insult to injury, she was unable to access the college education that had motivated her move without first transferring her US high school credits, a process known as revalidation. Without the ability to return to Georgia for the official apostille, or seals, the Mexican government required, it was five years before Maggie’s academics credits were deemed legitimate in her country of birth.

She felt alone. Loredo recalls retreating into herself and losing her confidence to speak in public. But at some point during this bleak time, she came across the work of a PhD student from Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México named Jill Anderson, who was bringing together the testimonies of Mexican deportees and returnees for a book called Los Otros Dreamers, which is now out of print. Maggie submitted an essay detailing her own experience and discovered that she was a member of a disperse, but vast community of young Mexican returnees. United through their work with Los Otros Dreamers and subsequent book tours (Loredo was able to get her joint B-1 business visit visa and B-2 tourist visa via an invitation to speak at UC Fullerton), the group formed a lasting collective they dubbed Otros Dreams en Acción to advocate for Mexican deportees and returnees.

Many returnees report encountering the US’ hateful anti-immigrant rhetoric reflected on the other side of the border.

In late 2017, the collective was able to file to become an NGO. One of its first moves as a legal entity was to establish a physical meeting point –Poch@ House – for deportees and returnees. The idea originated with one of the contributors to Los Otros Dreamers. “She would say, ‘Why isn’t there a place where I can just go and feel like I’m in a safe space?,’” remembers Loredo.

Poch@ House’s name is the reclamation of a word that is often wielded against Mexicans that grew up in or have integrated into US culture. “Most of us when we come back, we have been stigmatized or stereotyped by people here in Mexico,” says Maggie. “We’re trying to say, ‘OK yes, I’m a poch@ and that’s how I want to be named.’” Poch@ House has developed free English language conversation clubs with the intent of introducing Mexicans to actual deportees and returnees. Many returnees report encountering the US’ hateful anti-immigrant rhetoric reflected on the other side of the border. In many ways, the experience of those returning to their birth country can mirror the feeling of being undocumented in the US. “Come and take a conversation club and get to know us,” says Loredo. “Know that we’re not here to ask for privileges. Know that we’re not here to take your jobs.”

In April, these offerings will expand when English teacher and deportee Eduardo Aguilar begins the first term of Poch@ House’s “Social Justice English” courses. “What we want to do is offer a different way of learning English than the usual teaching program that they have here in Mexico, which is aimed towards business English,” says Aguilar. Lesson plans will revolve around discussing current events and social justice issues, such as gender. Deportees who want to improve their English language skills (among them people who first went to the US when they were older), will have free tuition.

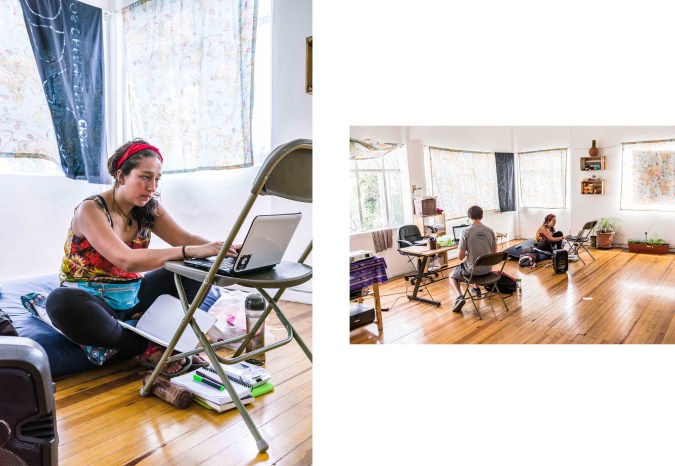

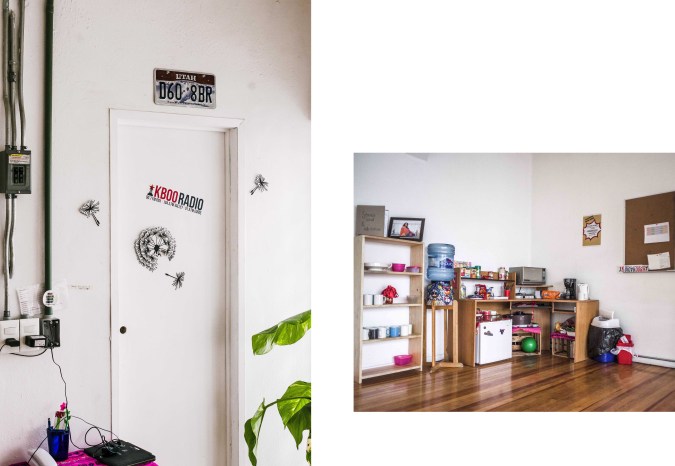

Poch@ House opened in January, its two rooms overlooking a street in Mexico City’s Barrio Chino full of sparkling lighting supply stores and kitty-corner from a small park. Inside, the space is well-lit and full of work spaces and book shelves. Community members can drop in from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Monday through Saturday for pointers on getting a Mexican ID card, unemployment benefits, and on understanding Mexico’s byzantine national income tax system. There are free yoga and African dance classes — people are encouraged to stop in even if they merely want to browse through an English language copy of Fire and Fury. “It’s a space where we can speak Spanglish,” says Maggie. “It’s a place where people can sit in a beanbag and have coffee, read a book — but also, combine culture and art as tool[s] for policy changes.”

In 2017, ICE utilized its $5 billion annual budget to deport 226,119 people from the United States. 81,000 of those deportees were already living in the US — some of them for decades. While overall deportation numbers have actually dropped since the Obama administration, so-called “interior removals” in the US went up 31 percent in 2017 compared to the same time period during Obama’s last year in office. The current administration’s resolve to leave no group of immigrants safe from deportation is clear.

In response to the inauguration of Trump, Mexico City mayor Miguel Angel Mancera and President Enrique Peña Nieto announced plans to welcome Mexicans forcibly removed from their lives in the United States. (In April 2017, CDMX also declared itself a sanctuary city.) But the changing profile of those being deported means the resources awaiting them must also evolve. “If a person hasn’t been here for 20, 30 years, obviously they don’t have connections to Mexico,” says Loredo. “Sometimes people don’t even have a place to stay — basic things.”

Mexico City officials say they are taking steps to meet the demand for reintegration assistance. In 2017, an module was set up in Benito Juárez International Airport to provide information to the 135 deportees that arrive on special flights from the United States every Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday — often with a single sack of belongings, having had their official documents destroyed in detention centers. The capital’s secretary of labor announced that 1,069 returnees (a figure that includes deportees and those who left “voluntarily”) received unemployment pay. The city held two returnee job fairs, and funded three self-employment projects including Deportados En La Lucha [DUL], a collective that sustains itself by silkscreening Deportados Brand t shirts and temporarily housing recent arrivals in a small loft above it’s workfloor.

But given the bureaucratic barriers that still exist — and are multiplied during presidential election years like this one, when Mexicans are unable to apply for new identification documents — few deportee and returnee advocates see these efforts as sufficient. ODA, DUL, and other groups have successfully pressured politicians to remove many barriers that Maggie encountered when she arrived 10 years ago, most significantly to the academic credit revalidation process, which was streamlined by modifications to federal law Acuerdo 286 last year.

Employment for returnees, who often arrive with less than perfect Spanish skills, is another issue. In Mexico City, they are often courted to work at the capital’s myriad call centers, which are able to capitalize on returnees’ bilingualism and US cultural fluency by paying wages far below United States standards (reportedly, slightly higher than the Mexican minimum wage of $4.71 USD per day) to those dealing with US companies’ disgruntled customers. Call centers require minimal documentation for job applications — typically, a high school diploma will suffice — but, “It’s not the best job to continue for years,” says Loredo. “You’re in a closed space with really heavy hours.”

ODA has made it a priority to form links to returnee employment programs that offer more sustainable opportunities. Among these are Hola Code, a five month software engineering bootcamp that provides stipends to enrolled returnees, with no prior technological experience required for admission. In April, the first group of 22 Hola Code participants will receive their certification. Poch@ House also pairs with the University of Dayton’s online TOEFL program that certifies returnees to teach English.

The organization’s immediate goal is acclimating returnees to their new life in Mexico, which Loredo, sitting at her desk in Poch@ House, emphasizes is full of its own joys. “Growing up in the US, you miss a lot of the culture. You miss a lot of the language, that connection with Mexico.” But ultimately, Otros Dreams En Acción believes in the importance of trans border mobility, of respecting bicultural individuals who have grown up loving, and being a part of, what both the United States and Mexico have to offer. “I have come to understand that I want to be de aquí, de allá,” says Loredo, gesturing to the words, which have been stuck in cut-out letters on the wall beside her. She is years away from the mute times, the lonely times, and knows that her life built on both sides of the border deserves recognition. “I don’t want to choose one.”