Growing up in San Diego, I remember watching my abuelito tend the guava tree he grew for my mother, while singing along to the Mexican rancheras that blared from his tiny radio in the backyard. When my mother called him in for lunch, he’d start whistling, as Linda Ronstadt’s Canciones de mi Padre echoed from the house. We both knew that we’d be eating caldo de res con arroz Mexicano. Once a month, my Filipino grandfather, or tata, would also pay us visits from San Francisco. I’d help him and my mother cook Filipino delicacies, like chicken adobo, pansit, and lumpia. He’d have us in tears, laughing at his jokes, while the smell of soy sauce and vinegar permeated the entire house.

Many of our family functions centered on moments like these – eating Filipino food while listening to Mexican music, bathing ourselves in the experiences that were for me, the essence of being a Mexipino.

For many years, I thought this identity was unique to me. Aside from my siblings, I didn’t know anyone else who was both Mexican and Filipino. But over the years, I found out I wasn’t alone. As I grew older, I met other friends who were also Mexican and Filipino. In college, this number grew far greater than I imagined. Together, we found community, sharing experiences about our families and lives that strengthened our sense of identity. We’d laugh at the fact that we had similar stories of eating both Mexican and Filipino food at family functions, and grew up with the same smells in our kitchens. One friend joked that he was the only guy in his barrio who ate burritos and bagoong. Another told me that his favorite things to eat at Christmas were pancit and tamales. We also bonded over the terms we’d created to label our mixed identities growing up, like Mexipina/o, Filicano, Chilipino, Chicapino, Jalapino, and fish taco. We were a growing population – one born from two separate communities that reflect this country’s multicultural history and mixed race identity.

The formation of Mexican and Filipino communities was one defined by exclusion.

It was these experiences, as well as the historical factors that led to this identity formation, that shaped my ideas for what eventually became my dissertation in graduate school and first book, Becoming Mexipino: Multiethnic Identities and Communities in San Diego (Rutgers University Press, 2012). Through the sharing of stories, oral histories, and research on the experiences of Mexipina/os, I found out a lot about the San Diego communities I grew up in, as well as what this identity meant for other areas with large Mexican and Filipino populations. I also learned more about who I was, and how far my family’s history is rooted in San Diego and the Mexipina/o experience.

Mexipinos in San Diego

San Diego has been an area of settlement for Mexicans and Filipinos since the early twentieth century. As a border town with Tijuana, the city has always had a continuous influx of Mexican migration. It is also located at the southernmost tip of a migration cycle that many of the early Filipino and Mexican laborers traveled, while working in the agricultural fields and fish canneries along the West Coast. In this way, it became home to the second largest Filipino community in the US, and is among one of the more popular destinations for Filipino migrants today.

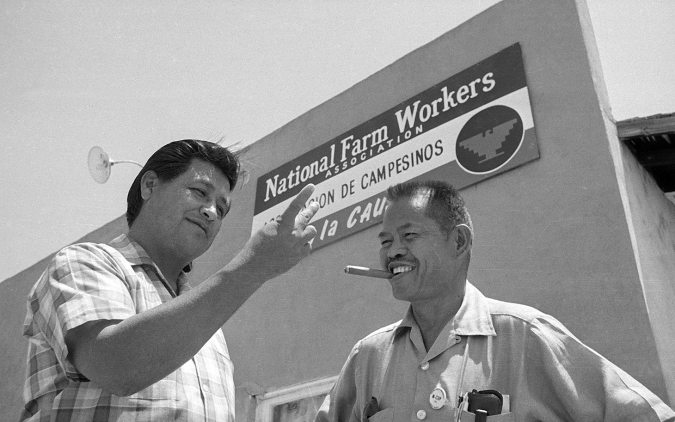

As laborers, Mexicans and Filipinos were both relegated to the hardest, lowest paying jobs in agriculture, fish canning, and service work in the hotel and restaurant industries. This kept them in constant contact with each other, a relationship that proved useful when they organized in California’s agricultural fields throughout the twentieth century. The most recognized of these interethnic unions was the United Farm Workers, which was comprised primarily of Mexican and Filipino union members at its onset.

The formation of Mexican and Filipino communities was one informed by exclusion. Through restrictive covenants, redlining and racial segregation, both groups were often relegated to living in overlapping communities along with Chamorros, Samoans, Tongans, Native Hawaiians, Blacks and Southeast Asians (among other groups). These communities were located in or around the South bay, Southeastern, and downtown sections of San Diego. In these communities, Mexicans and Filipinos lived, worked, and attended the same Catholic churches, such as St. Mary’s in National City. As a child I remember seeing familiar faces, Mexican, Filipino, and Chamorro during mass and at catechism class. Stories from former residents of the community of Barrio Logan also highlighted the fact that there were various Mexican social clubs and rock-and-roll groups in the area that had at least one, if not more Filipinos or Mexipinos in them. These were but a few examples of how both groups interacted with each other on various levels in their communities.

The Navy was also a major contributor to Filipino migration to San Diego. The Naval Training Center (NTC) in San Diego brought in many Filipinos directly from the Philippines. Most of the early Filipinos to San Diego were young, single men. As bachelors, Filipino men sought companionship and love. Due to miscegenation laws and even violence by whites, Filipino men were prevented from marrying white women. However, many Filipino men also chose to marry Mexican women and other Latinas. It was Mexican women however, who proved to be the preferred spouses for Filipino men.

Historical Roots of Mexican-Filipino Connection

Because both shared a Spanish colonial past, they often had similar cultural practices.

In looking at the background of both Mexicans and Filipinos, it made sense that Filipinos and Mexicans found commonalities and intermarried. Given their shared Spanish colonial past, both groups shared a similar culture, Catholic religion, and to some degree, language. Mexicans and Filipinos had first contact with each other during the Acapulco-Manila galleon trade that flourished between 1565-1815. Indigenous and mixed race Filipinos were oftentimes the crew members on these galleons, laboring as slaves, servants, and sailors. Upon reaching the shores of Acapulco, Mexico, many Filipinos jumped ship and blended into the local population, marrying indigenous and mixed race Mexican women. The descendants of these Filipino-Mexican relationships still reside in Mexico. This coming together in a cultural exchange of goods, language, and interrelationships, had a lasting impact on the histories of both Mexicans and Filipinos and continues to this day.

This was the historical underpinning of what Mexicans and Filipinos came to share in the twentieth century in places such as San Diego. Because both shared a Spanish colonial past, they often had similar cultural practices. Filipino debutantes are similar to Mexican quinceañeras, a coming of age party for young Filipina and Mexican women. Both celebrate religious and community fiestas, and have strong ties to family, both immediate and extended. They also share in the practice of compadrazgo, or God parenthood. This experience reinforced familial and kinship ties as Filipinos and Mexicans intermarried and baptized each other’s children. It is experiences such as these that provided the immediate connection between both communities – an understanding that gave rise to several generations of Mexipinos in San Diego, my family included. Even today, with a greater influx of Filipina women to the US, both groups continue to intermarry. Not only did Filipino men continue to marry Mexican and Chicana women, but Mexican and Chicano men marry also married Filipina women. These bonds, though not always conscious, continue to have a lasting impact on both communities.

[Editor’s Note: In this section, the author has focused on heterosexual relationships, given that same sex couples were not able to marry until recently.]

Forging an Identity

Looking back at the city’s Mexican and Filipino communities, as well as my own family history, has given me a greater understanding about myself, and the distinct experience I share with other Mexipinos. It was my lived experience, but not much had ever been written about it. As such, I decided to write my communities into existence and be part of the historical memory of San Diego, writing about this topic in graduate school, and eventually framing my teaching and research trajectory around comparative ethnic studies. I see the Mexipino experience as part of a larger Latinx, Asian and Pacific Islander story of migration, intermixing and community formations both in the US and abroad. Indeed, as a distinct group within two separate overlapping communities, I understood for example, that these identities were the bridge that reinforces the already close historical bonds between Mexicans and Filipinos. We are proof that multiplicity can be a positive experience. However, I will be the first to point out that this is not a perfect relationship – there were at times both economic and social competition between Mexicans and Filipinos. Some of the other Mexipinos I spoke with, as well as my own experiences, have shown that often times we have to prove to both Mexicans and Filipinos that we are “Mexican or Filipino enough.” Our physical appearance comes into question at times, as does our ability to speak either language. We have to at times, show our cultural authenticity in order to be accepted, while other times we are embraced by both communities.

Yet, I think that the close ties that we have to our families, friends, and community, far outweighs any negative experience. Our lives are a reflection of two communities coming together and as a product of this experience over several generations, we owe it to our family, friends, and others to be one voice that intersects multiple communities, far beyond our own borders. We are Mexican, we are Filipino, and yes, we are Mexipino, among other terms. And as Mexipinos, we provide a new way in which to see our mixed race communities, and the world around us.

This article was originally published in Mavin Magazine. A revised version appears here, published with permission.