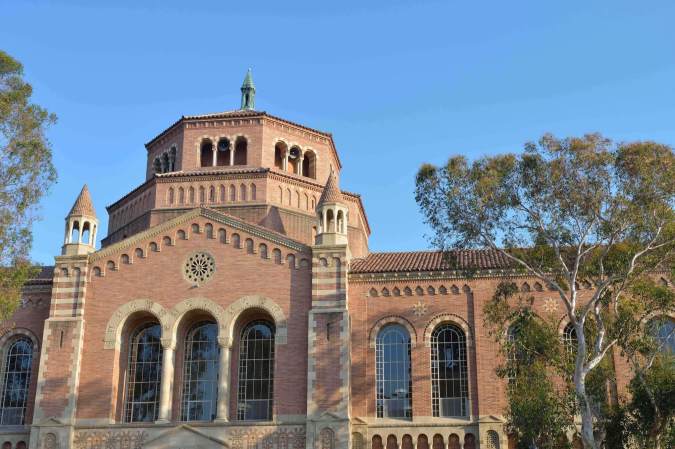

I was 19 years old when I frantically demanded that my University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Chicana/o Studies professors explain to me why there was only one book in the school library on U.S.-based Central Americans. My professor, Alicia Gaspar de Alba, explained that it takes time to produce published research and that if there was a book I could not find, I should consider writing it. That day a fire sparked inside of me. My Chicana/o Studies professors pointed me in the direction of social inquiry and before I knew it, I was in a Chicana and Chicano Studies doctoral program at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where I was able to conduct research on the Central American experience in the U.S. that was rooted in social justice and cultural resilience.

The goal of Chicana and Chicano Studies is to build upon the knowledge of community.

I am a U.S.-born Salvadoran-Mexican. I am a scholar of Central American Studies, Chicana and Chicano Studies and immigrant integration. All three of my degrees – my B.A., M.A. and Ph.D. – are in Chicana and Chicano Studies from UCLA and UC Santa Barbara.

Recently, faculty at UCLA’s Cesar E. Chavez Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies voted 15-1 to change the name of the department to the Cesar E. Chavez Department of Chicana, Chicano and Central American Studies. The amendment is a reflection of work that has taken place within the department for at least 10 years – if not longer.

Since I graduated from UCLA in 2010, the Latino student body has grown and diversified, mirroring demographic changes in the city overall. Los Angeles is now the second-largest Salvadoran city by population in the world, outside of San Salvador, the Central American country’s capital. The name change is reflective of the institutional urgency to address the needs of a shifting urban reality. Not unlike the young scholars of the past who advocated for Chicana and Chicano Studies departments, undergraduate and graduate students at UCLA wrote letters in support of the new name and listed their reasons for the push toward inclusivity.

However, a recent op-ed on The Daily Chela argues that the name change is due to pressure from a “faction of students” who are demanding that their Central American heritage be included in the Chicana/o experience. In the piece, author Brandon Loran Maxwell contends that altering the name of a department or an organization with “Chicano” in its title contributes to the erasure of the specific history of that space and to the eradication of the contributions made by activists who worked hard to establish those spaces.

The fear of erasure of specific Mexican cultural history that Maxwell expects will come from changing the names of institutions is a fear all too familiar to Central Americans. But including Central American Studies is not co-opting Chicana/o Studies or otherwise eradicating it.

The inclusion of Central American Studies does not minimize Mexican history.

The most important lesson I learned in my scholarly training was that the goal of Chicana and Chicano Studies is to build upon the knowledge of community. If we, as informed members of the public, are to build, we must do so on a solid foundation. Chicana and Chicano Studies departments and programs in the Southwest U.S. have some of the most solid institutional foundations. Therefore, it would follow that the study of ethnic difference rooted in community and social justice would benefit greatly from the gains activists and faculty fought for to hold these spaces for decades.

As a student, I found myself studying Central Americans in Chicana/o Studies because the frameworks of transnational social justice and of U.S.-based racial and ethnic otherness applied to my population of interest. The inclusion of Central American Studies does not minimize Mexican history. The histories of Mexicans, Central Americans, Caribeños and South Americans in the U.S. are intrinsically linked because all of these people are racialized as Mexican and dismissed in the ways Mexicans are dismissed.

My time in the Midwest as a professor at DePaul University’s Latin American and Latino Studies department has shown me that in other regions of the U.S., Latina/o Studies departments draw upon social justice frameworks established by Chicanas/os, Puerto Ricans, Central Americans, Dominicans, Cubans and others. What unites our work is the pursuit of social justice, equity and respect for the varied experiences of members of Latino communities – particularly those who find themselves in the most precarious situations, like poverty, detention and social dejection.

The racial framework that exalted whiteness and excluded Black and Native American populations from full personhood is still at work among Latino populations and is something we have to continue to work on dismantling. The legacy of colonization in Latin America means we are people of multiple skin tones, language practices, cultural heritages and religious affinities. The official incorporation of Mexicans into the U.S. gave way to policy that gave Mexicans the right to become citizens if they met specific criteria while the people in territories and nations the U.S. did not formally incorporate remained relatively disenfranchised.

Our histories have more commonalities than differences.

But our histories have more commonalities than differences. In the U.S., the most readily available framework of intelligibility to try to understand the experiences of Latinos is the framework of the Mexican presence. Mexican-American populations are the largest of all the Latino groups, have the longest-standing formal political organizations and have made the biggest strides in their fights for equality and inclusivity, largely because they have been in the U.S. in a critical mass since the time of Mexican annexation in 1848.

However, non-Mexican Latinos have lived in the Southwest U.S. for as long as Mexicans have. According to David Hayes-Bautista’s book, El Cinco de Mayo: An American Tradition, mutual aid society contribution log sheets from 1860s Cinco de Mayo fundraisers indicate the nationalities of donors as Salvadoran, Chilean and Peruvian. Guatemalan activist Luisa Moreno led factory labor organizing efforts in the 1930s for the American Federation of Labor, which transformed the way we think about labor rights in the U.S. When the youth of East Los Angeles marched in the Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War in 1970, Central Americans were there – shoulder to shoulder.

Academically, non-Mexican Latinos were also a part of the Chicano education fight. When UCLA undergraduates pitched tents in the campus green demanding the establishment of a Chicana and Chicano Studies Department with faculty tenure lines in the 1990s, Central Americans were there.

The future of the fields of Chicana and Chicano Studies and Central American Studies is the pursuit of the construction of full personhood and justice for people in marginalized communities who face difficulty every day. If you look around you will notice our people are dying at the border, families are being separated and political engagement among our communities is lacking.

We have a lot of work to do, so let’s dive in.