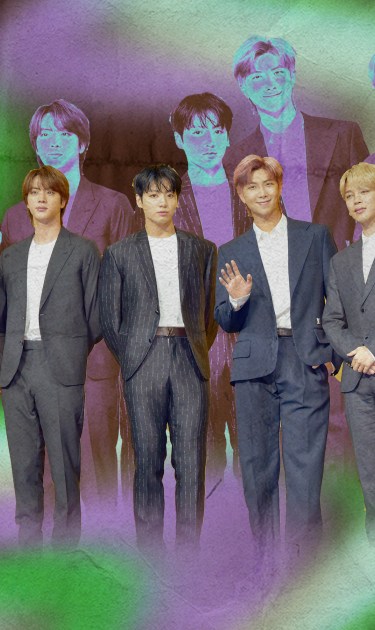

There’s no denying that South Korean mega-group BTS has taken the world by storm. The K-pop ensemble is a worldwide sensation, their music being listened to in over 50 countries, and their supporters, the BTS Army, ranging in the tens of millions. This is why it came as a shock to many fans when a Dominican radio-podcast host for Esto No Es Radio referred to the band as “Los Backstreet Boys chinos” (The Chinese Backstreet Boys) in one of their radio episodes back in August, even though the show’s hosts were fully aware and reiterated multiple times in the same episode that the band is Korean.

The band’s supporters quickly came to BTS’s defense and demanded an apology from the show, one that seemingly has not been issued. The show has since insisted that there was no racist intention behind their comments, which did not sit well with fans. Sadly, misidentifying and calling all Asians “chino,” regardless of them being Chinese or not, is far from a rare occurrence in Latin America. So much so that not even one month earlier from the Dominican radio controversy, the Colombian radio station La Mega also came under fire after hosts from their program El Mañanero used the same term “chinos” to refer to BTS when introducing their song. A few days later, the hosts “apologized,” but their apology did more harm than good, as they doubled down on their offensive comments and continued to mock Asian cultures and BTS fans by wearing anime (widely known to be Japanese) wigs and playing the Korean national anthem while laughing and dancing mockingly.

At first glance, most Latines would simply brush off these types of comments and not bat an eye at all given the normalization, but as an Asian-Latine myself, the second I heard the word “chinos” in this instance, it sent a cold chill down my spine and my blood boiled with rage. “Casual” derogatory words are used so much in everyday dialogue that it’s sometimes seen as a form of endearment versus the normalized ignorance that it is.

Growing up in Colombia as a Japanese descendent, I have been subjected to a lot of anti-Asian hate. This term, in particular, is one of the standouts. I remember it being used as an “affectionate” nickname by some classmates, and their tone seemed genuine, friendly even. But as I’ve grown older and seen firsthand the spectrum of xenophobia and anti-Asian hate, I can’t help but look at the many, many times I was called “china” in an alienating light.

This casual racism and xenophobia are so normalized in Latine vernacular that it’s even made its way into our music. Look at “Ojitos Chinos” by El Gran Combo de Puerto Rico, which fetishizes the eyes of Asian women and uses “chinos” as a form of affection to comment on our “exotic look,” yet in the same song where a “term of endearment” is used, Asian accents are mocked.

In my experience, most Latine people find the term humorous and don’t associate it with harmful intentions. However, it is clear that the word has a microaggressive tone and intention behind it. It works against us, especially when we fight hard to be accurately represented in mainstream media. Personally, I felt disconnected from my roots for a long time out of fear of being mocked for being Asian, and it wasn’t until recently with films like Crazy Rich Asians and Shang-Chi that I came to terms with my intersectionality. This is why it’s so heartbreaking when established and popular Latine shows and their hosts continue to use disrespectful language because it shows just how far we still have to go as a community in order to be respectful and inclusive.

More so, calling every one of us “chino” erases how unique and diverse all our cultures are, further stripping us of our identities while perpetuating an idea of “otherness”—one that is easily comparable to Americans referring to all Latine people as “Mexican.” Using language like this dismisses our own individual identities and further perpetuates this “us against them” dynamic, allowing for our diverse cultural backgrounds to be ostracized under the guise that “así es la cultura aquí,” or that’s just how the culture is.

While it might not seem like any harm could come from it, it’s through small comments like these—the ones that we don’t think twice about—that hateful speech and ideas begin to boil. Just in the last year, there’s been an exponential rise in anti-Asian hate crimes as a result of COVID-19, and it’s through using words like “chino” and “china” that group all Asian communities together, that people feel empowered and entitled to enact these horrible crimes against this “other” group of people. Because whether we like it or not, language holds a lot of power, and by not confronting these “insignificant” remarks and calling people out on them, we’re normalizing dangerous and harmful stereotypes that can and have put people in actual danger.

Movements like #StopAsianHate have been created in order to bring awareness to and combat this issue, but we all have to make a conscious effort to stop giving our communities free passes to get away with racist and xenophobic remarks just because “that’s how it’s always been.” And hopefully, one day, BTS and groups just like them will be able to be enjoyed by people without there being hurtful name-calling involved. But most importantly, young Asian children growing up in Latin America won’t have to grow up being alienated from their cultures or stripped of their diversity—and instead, be treated with distinction and respect.