Be About It is a column in which we dig into the philanthropic, necessary work our community is heralding or participating in. We encourage you to read about it and be about it.

In October 2006, some students and I attended a Halloween tour of Sunnyside Cemetery in Long Beach, California. The tour’s eeriest moment came when our guide, dressed in Victorian garb, led us to a crabgrass-covered grave. As we assembled, our pretend Victorian explained that we were gathered at a high school teacher’s final resting place. Jane Elizabeth Harnett had worked on our campus, Long Beach Polytechnic High School, until the 1918 influenza pandemic claimed her life. Harnett died at age 44.

“What did she teach?” I asked. The guide’s answer was as poetic as it was macabre, “History.” My students looked at me, their history teacher, with concern. I decided not to ask if any of the teacher’s students were buried in the cemetery. They likely were.

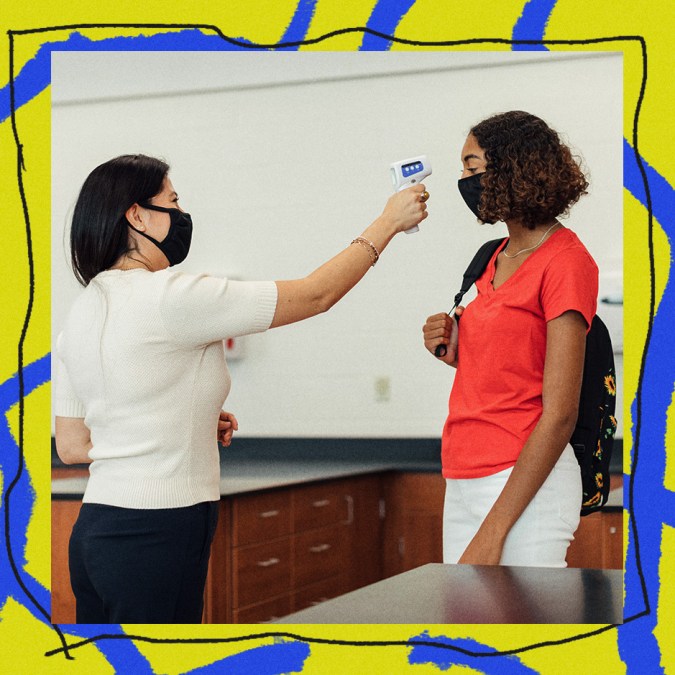

As history repeats itself, a virus again threatens those of us involved in public education and, while the 1918 pandemic killed many healthy young adults, COVID-19’s full impact on the United States’ young adult population remains to be seen. Last year, high schools across the country transitioned to remote learning, enabling students to quarantine. As districts announce plans for re-opening, anxiety runs high. Fear is especially acute among immunocompromised people as well as members of racially minoritized groups. Reopening plans, however, rarely seem to address the critical concerns of these constituencies.

“I wear a mask and sanitize constantly,” incoming junior Adrian Stinardo tells Remezcla. “I don’t go into small enclosed buildings.” Stinardo points out that schools often close in response to “a little snow in the road” and asks, “Now that there’s a pandemic that will wipe out students and teachers and parents we’re considering… reopening?”

Stinardo is a mixed-race 16-year-old from Seattle, Washington. To curb the spread of the coronavirus, his high school closed its doors in mid-March and, like many others, replaced on-site instruction with chaotic remote learning. Despite the difficulty created by this shift, he says that the thought of anyone returning to campus for in-person instruction makes him uneasy—and there’s a trend in who’s choosing to do that.

When Jon Valant, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, analyzed demographic and political data related to campus re-openings, he found that school districts in counties that supported Trump in the 2016 election were much likelier to have announced plans for face-to-face instruction. These plans endanger all students but place racially minoritized kids in especially heightened peril.

According to NPR, Black and Hispanic kids have been much likelier to require hospitalization for COVID-19. For Hispanic kids, the likelihood has been eight times higher than for white kids. For Black kids, the likelihood has been five times higher.

Scholar activist Ruth Wilson Gilmore wrote that “racism is the state-sanctioned…production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.” When seen through Wilson Gilmore’s lens, it becomes clear that students made to endure face-to-face instruction will be taught about eugenics through experiential learning.

Reports show that racially minoritized young adults are receiving suboptimal medical attention. The results have been lethal. On March 24, a 17-year-old boy from Lancaster, California became the state’s first juvenile to die from COVID-19. According to Time, a Kaiser facility rejected the teen for treatment. He later died en route to Antelope Valley Hospital. Lancaster Mayor R. Rex Parris appeared to scapegoat the boy’s immigrant family for his death, stating that the “boy’s father [spoke] English as a second language,” musing that this caused a “misunderstanding.”

Luis Luna, an incoming senior at Long Beach Polytechnic High School this year, is anxious about coronavirus exposure. The 16-year-old calls the 90813 zip code—which he shares has the highest rate of coronavirus cases in the region—home. The area is, you guessed it, primarily people of color. He contrasts his neighborhood’s pandemic experience with that of 90808. That area enjoys the lowest rate of infection and it’s no coincidence that the neighborhood also happens to be rich and white as hell. Luna fears that pressure from white and wealthy residents to return to in-person instruction will force him, and his family, directly into COVID-19’s crosshairs.

Luna describes the online learning instituted by the district come April as “a hassle,” but defends remote instruction as necessary and life-saving. Like Stinardo, he takes strict sanitary precautions and hasn’t hung out with his friends since schools closed in April, but he admits he became “super depressed and stressed out” by the pandemic and those issues interfered with his ability to learn.

Resisting a school district’s dangerous plans for on-site instruction would be both an act of self-care and revolution. Students have more power than they think—together you can disrupt racist plans and shape district policy. One way for young people to achieve these goals is by taking control of attendance. School districts generate revenue by reporting average daily attendance data and, because each student has the potential to generate thousands of dollars, administrators have built huge bureaucracies that monitor, track, and control the location of young people’s bodies.

Under these regimes, truancy officers act as bounty hunters and while they might be able to effectively capture small numbers of kids, they lack the resources to deal with massive organized resistance. Such large-scale efforts could take the form of strikes that might bring students, staff, teachers, and parents in solidarity with one another. Boycotts offer another tool. In the 1960s, the United Farmworkers convinced millions of consumers to stop buying grapes. The campaign worked, and grape growers capitulated to farmworker demands. A boycott of public schools could produce similar results. A school ought to be a site where life is valued and is treated as precious. Racist schools do the opposite and, under such circumstances, ditching is life.