In 2012, Stephanie Gomez became pregnant after having sex for the first time. She was 18 and a senior in high school. Instead of planning her prom night, Gomez made plans to get an abortion at her nearest Planned Parenthood in Houston.

“I didn’t know what to expect,” she recalls. “I didn’t know what the procedure would be like, I didn’t know what it would cost and I didn’t really care. I just knew that I wasn’t going to be pregnant.”

Gomez was scared, alone and grappling with several concerns. She was terrified that her Salvadoran parents would find out, of course, but she was also in an abusive relationship with the boy who got her pregnant and grappling with her Catholic faith. Plus, she didn’t know whether it was even legal to get an abortion in Texas.

“I didn’t know that people had abortions,” Gomez says. I thought it was a criminal act.”

“I didn’t know that people had abortions”

Abortion is legal in Texas, but over the last decade, state legislation has drastically restricted access to both abortions and reproductive healthcare overall. People of color—including Latinxs who already face unique challenges accessing reproductive healthcare due to cultural stigma, economic barriers, immigration status and more—are disproportionately affected by these laws.

The coronavirus pandemic has exacerbated the challenges Latinxs face even further. In late March, Texas banned nearly all abortions. Gov. Greg Abbott suspended all surgeries not deemed “immediately medically necessary” to conserve medical resources for coronavirus patients. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton included abortion as a “non-essential” medical procedure and prohibited it, with exceptions only to save a pregnant person’s life. The order resulted in a legal back and forth between courts. However, the near total-ban was lifted on April 22, after Abbott allowed more medical procedures to resume—including abortions.

Gomez learned she was five weeks and four days pregnant when she went in for her sonogram appointment. She would have to return to the same clinic 24 hours later to get the abortion—a waiting period required by Texas law. The clinic was able to connect her to a local abortion fund to help pay for half of the procedure but Gomez needed an additional $300 to pay in full. Gomez worked at McDonald’s at the time and knew she couldn’t afford it, but had to find a way to fund the procedure—and fast, because the price increases the longer you wait.

“I was not in a situation where I could afford even a $50 increase, much less one of a couple hundred dollars,” Gomez explains. “And I needed a ride, so I was at the mercy of the person who impregnated me [and] was abusive. I was on his schedule and if [it] did not line up correctly, it wasn’t going to happen. And I said that I was not going to be pregnant. I didn’t want to be pregnant.”

A Decade of Reproductive Healthcare Restrictions

After conservative politicians swept the House and gained more seats in the Senate in the 2010 midterm election, they began a nationwide effort to restrict voting rights. At the same time, a wave of anti-choice laws similarly swept the country, according to a 2016 analysis by Rewire News. The simultaneous nature of the two was hardly a coincidence—conservatives used the same tactics to curtail the rights of people of color and women (particularly those with low incomes). In 2011, 36 states enacted a then-record 92 new laws that restricted abortion and targeted abortion providers by creating medically unnecessary requirements with the goal of shutting them down. It was only the beginning of an onslaught of abortion restrictions across the nation and especially in Texas.

That same year, Texas lawmakers reportedly slashed family planning funding by two-thirds, effectively cutting access to sexually transmitted diseases (STD) testing, cancer screenings and birth control.

Nancy Cárdenas Peña, Texas Associate Director for State Policy and Advocacy at the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice, says the cuts“wiped out the safety net”for people who regularly accessed reproductive health care at clinics at a low cost. “This was definitely an attack on abortion-centered work,” she explains. “Most of the clinics that didn’t even provide abortion services were closed because of the effects of the 2011 cuts.”

Texas has the highest rate of uninsured people in all of the United States. 61% of those people are Latinxs. Many uninsured Latinxs relied on these low-cost services—some of which were life-saving. Cárdenas Peña points out Latinas have the highest rates of cervical cancer in the United States according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Texas has the highest rate of uninsured people in all of the United States. 61% of those people are Latinxs.

A year after these cuts were introduced, Texas enacted HB15, which requires a mandatory sonogram 24 hours before an abortion, unless a patient lives more than 100 miles away from the nearest clinic, in which case the waiting period is two hours. This meant patients would have to make time for two trips to an abortion provider and ensure the same physician who is set to perform the abortion is able to perform the ultrasound. They’re also obliged to give a verbal explanation of the images and provide patients the option to listen to a fetal heartbeat.

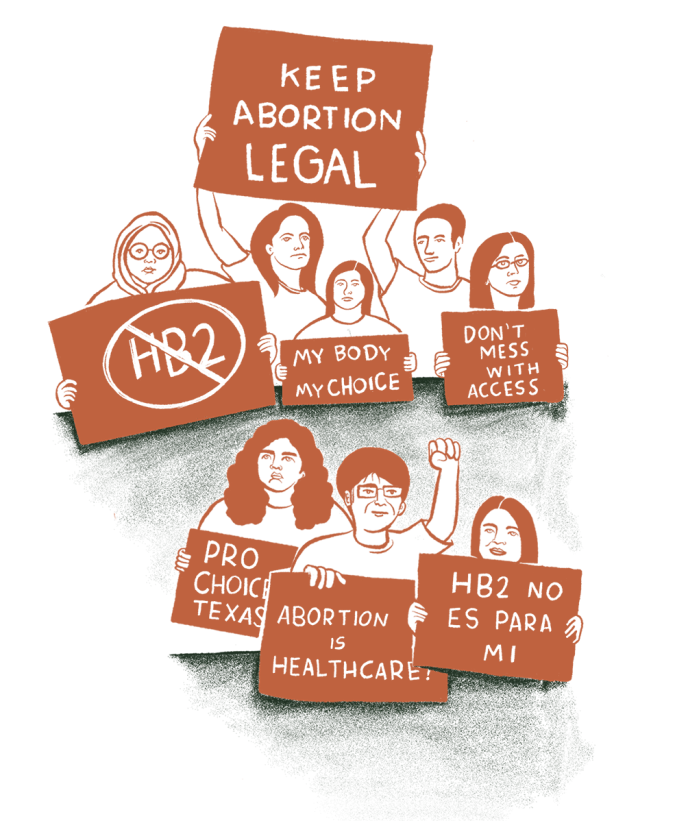

In 2013, Texas lawmakers passed one of the strictest abortion laws at the time. After two special legislative sessions which included Wendy Davis’ memorable 13-hour long filibuster and “the people’s filibuster”, Governor Rick Perry signed HB2 into law. It included four abortion restrictions. Abortions were then banned after 20 weeks and physicians who performed abortions had to have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles of the facility. The law also tightened guidelines around abortion medication and abortion facilities had to meet hospital-like standards of ambulatory surgical centers. The bill consequently shuttered more than half of the 40 plus abortion facilities open before HB2, leaving only 19 facilities to serve the entire state of Texas in 2014.

According to an analysis of state data by the Dallas Morning News, Hispanic women were affected far more than any demographic as a result of this law. There was an 18% drop in abortions for Hispanic women in Texas from 2013 to 2014—that’s three times more than previous years. The report attributes most of that decline to abortion clinic closures in the Rio Grande Valley area, which is predominately Latinx.

The Center for Reproductive Rights filed a lawsuit in April 2014 on behalf of Whole Woman’s Health and other abortion providers, challenging HB2’s two key restrictions: the admitting privileges requirement and the ambulatory surgical standard requirements. For the next couple of years, the lawsuit was ping-ponged between courts. By 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments for the case and ruled the two provisions of HB2 unconstitutional, stating the requirements placed an “undue burden” on abortion access. However, by the time the Supreme Court overturned the key restrictions, the damage had already been done.

“Even though it wasoverturned by the [Supreme] Court, unfortunately, what HB2 was meant to do, already happened and it closed the majority of the clinics in the state of Texas,” Cárdenas Peña explained. “It forced communities that already had very little to no access to reproductive healthcare to drive [for] extended periods of time, to waste much more money accessing simple procedures that they have access to at a clinic in their local communities.”

The Unique Challenges Latinas Face to Access Reproductive Healthcare in Texas

At time of publication, there are 23 clinics open in Texas. For some cities, the nearest one is hundreds of miles away. That being said, travel clearly makes it increasingly difficult for people to access abortion and creates an economic barrier for many people of color, including Latinxs, since many patients have to take time off of work, find childcare for their kids or spend money on travel and lodging—on top of the cost for the procedure. The average cost of an abortion in Texas starts at around $450, however the price varies depending on the provider and how far along a person is in their pregnancy. In addition, Texas passed a law in 2017 that prohibits primary health insurance plans to cover abortions.

Gomez—who is now 25 and on the board of directors for Fund Texas Choice—was finally able to get an abortion with the financial help of her twin sister who picked up more shifts at the Denny’s she worked at. It was the first time she defied what society thinks a “good immigrant daughter” should be and, instead, did what was best for herself.

“The actual physical act of getting the abortion is probably the first time that I took agency over my bodyand decided to do what was best for me,” Gomez reflected. “Despite what I had been told by my culture or as a Catholic, it was empowering.”

Erika Galindo, an organizer at Lilith Fund, an abortion fund that offers financial assistance for procedures in Texas, says Latinxs can endure “a very intense stigma” when accessing abortion, which can take an emotional toll. In a recent win for the organization, the city of Austin approved a budget amendment which allocates $150,000 to organizations that help women with incidental expenses when seeking an abortion. Austin is the first city in the country to directly fund practical support for abortions.

“Texas is big, we have a lot of needs and those include things like childcare, lodging, transportation, and doula support or emotional support because a lot of our clients are experiencing [abortion] alone,” Galindo said. “Stigma is real and our clients can’t tell anybody that this is happening for whatever reason. This might be a huge emotional toll or burden on them, so we’re trying to get them doulas and make that available to people regardless of their income.”

For undocumented people living in the Rio Grande Valley, near the Texas-Mexico border, accessing reproductive healthcare presents even more challenges.

“Since McAllen is the only city south of San Antonio that has an abortion clinic, it can’t serve all one million people here in the Valley,” Cathy Torres, an organizer with Frontera Fund—an abortion fund serving Rio Grande Valley residents—says. “So if you’re undocumented and you need an abortion outside of the Valley, you aren’t able to venture into another city north of here because of the checkpoint. It’s criminalization of our bodies and a hyper militarization of our roots. [It] causes an extreme barrier to folks who are undocumented or who live in mixed-status families.”

Mariel Larios, a 28-year-old from El Paso, was the main provider for her mixed-status family when she got pregnant three years ago. A few months prior, Larios was tired of working “dead-end” jobs to financially support her parents and decided to pursue a college education to make a better life for herself.

When she got pregnant, she was in a new relationship with someone who was in the military and could be deployed at any time. This uncertainty, coupled with the changes she wanted to make in her life, made Larios come to the conclusion that having a child was not something she was ready for.

“As someone who wasn’t involved in politics or wasn’t involved in, really, anything… I was unsure that [abortion] was even an option,” she says.

After doing a Google search, she encountered a “crisis pregnancy center” or a fake clinic. Crisis pregnancy centers are non-medical facilities that present themselves as medical facilities and offer medically inaccurate services, with the ultimate goal of preventing people from accessing abortion services. Larios called a fake clinic and was lured in by the promise to speak to someone about her options.

“In my head, I was like, ‘wow, this is awesome, I can talk to somebody about this because I didn’t feel comfortable talking to anybody.”

But once she went through the first door, Larios realized she was in a religious space.

When she arrived for her appointment, the lobby looked like a clinic to her. There were magazines on the table, couches and a person sitting behind a glass window. But once she went through the first door, Larios realized she was in areligious space.A woman asked her to take a pregnancy test and didn’t leave the room. In the next room, the woman grabbed her hand and started praying and reciting biblical verses.

“I was very uncomfortable,” Larios recalls. “It made me feel so vulnerable and just stupid, like I felt really dumb being in that space, just knowing that I’m 25. I’m basically an adult and I ended up falling for this crap.”

Larios was discouraged and frustrated about not finding the information she needed at first but continued on with her research. She finally found a clinic, formerly known as the Reproductive Center, that laid out the abortion process for her. Larios got the information she needed and was able to fund her $600 abortion through the financial aid money she received to attend college.

“If it were any other point in my life where I was just working, it wouldn’t have been a possibility for me,” she explains.

Besides her financial challenges, Larios says the biggest barrier she faced was a lack of information and support, which is what she advises those considering abortion seek—whether that be financial, emotional or mental support. Instead, she recalls the cultural stigma around abortion amongst Latinxs.

“In our heads, we already become a bad person for doing this so we don’t seek help or support because we think we’re doing something bad,” she explains.”In reality, we’re just making a choice of what we want to do with our lives and what our options are.”

“My best advice is to look for resources and don’t give up if that’s what you want to do and don’t let the government or the particular state that you live in make those choices for you.”

Resources

West Fund

Fund Texas Choice

Lilith Fund

Tea Fund

Clinic Access

Planned Parenthood

Whole Woman’s Health Alliance

Map of Texas abortion clinics

Credits

Written by Yvonne Marquez

Illustrated by Claudia Gizell Aparicio Gamundi

Audio by Itzel Alejandra Martinez

Edited by Ecleen Luzmila Caraballo

Produced by Itzel Alejandra Martinez