Our Heritage Month offers a critical moment to talk about the often-hidden experiences of eating disorders in Latine communities. For both of us, anorexia isn’t just about restricting food—it’s about control, identity, and cultural contradiction. I, Carmen, reached a terrifying 60 pounds by age 13. I, Emillio, who also struggled as a teen, recalled “when I could touch my spine and play it like a xylophone, to an empty tune only I could hear, I felt proud—like I had finally made it.”

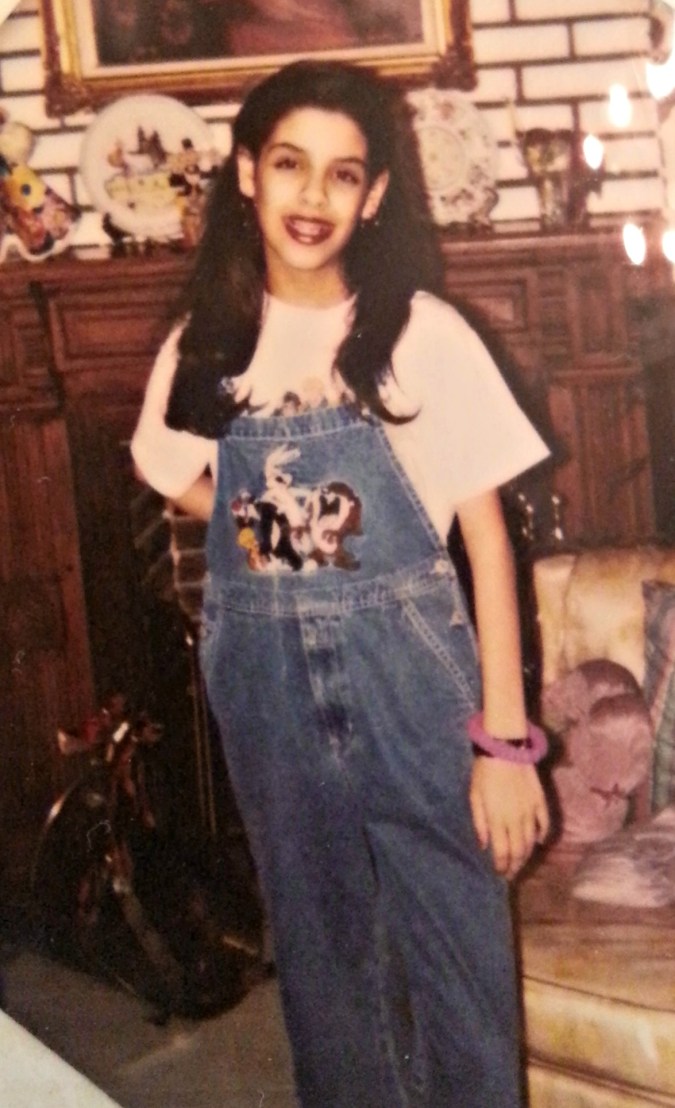

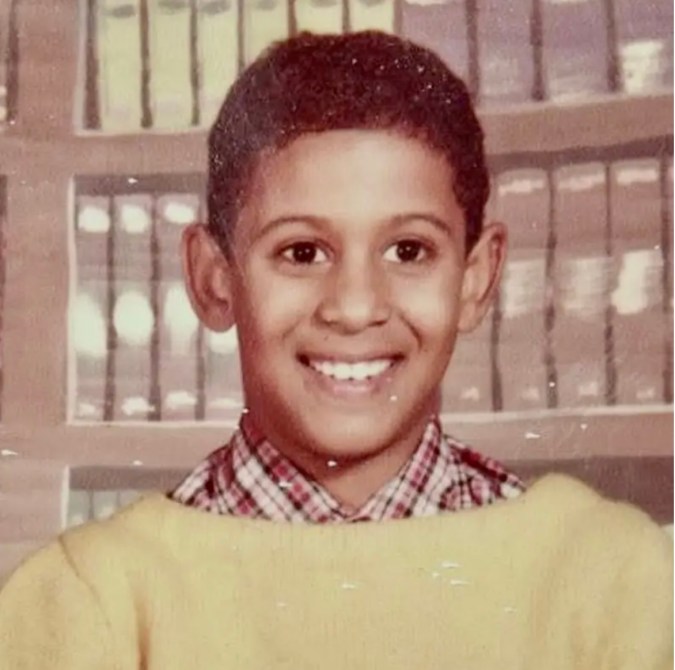

As Hispanic older millennials who came of age in the late ’90s and early 2000s, we navigated a bicultural landscape that significantly shaped our experiences with eating disorders. While American society, with its then-dominant “heroin chic” aesthetic epitomized by models like Kate Moss, promoted an unnaturally thin ideal, our Latine upbringing presented a contrasting image of beauty embodied by icons like the late Selena Quintanilla and Ricky Martin.

Their celebration of fuller figures, darker complexions, and bilingualism offered the validation we often found missing in mainstream American media. Unfortunately, though, like many young Latine individuals, we internalized the feeling that our inherent selves were “too much”—not solely in a physical sense dictated by U.S. standards, but also culturally, as we were subtly and overtly encouraged by media, peers, and, sometimes, even family to shrink ourselves, both literally and figuratively, within this bicultural tension.

We were born and raised in the vibrant, food-centric cultures of New Jersey and New York, my roots Cuban, Emillio’s Dominican. The pernil, flan, the arroz con pollo, the mofongo – once sources of comfort and celebration – became enemies, symbols of the bodies we desperately wanted to erase.

Like many young Hispanic women and men, we internalized the message that our natural forms were somehow “too much,” a deviation from the dominant image of beauty. We are told, directly and indirectly, that the thin, waifish ideal is the pinnacle of attractiveness, and that our own bodies, with their inherent diversity, are somehow lacking.

According to a 2023 National Alliance for Eating Disorders study, “older generations teasing younger generations at family gatherings, with names like ‘Gordo’ or ‘Gordita’ – meaning ‘fat one’ or ‘fatty’ due to their size. When respected family members negatively comment on an individual’s physical appearance, body type, or eating habits, their words can significantly impact that individual.”

For me, Emillio, my father said, “That mouth of yours will get you in trouble,” he would laugh while grabbing my love handles in public, humiliating me. I started skipping meals. Each pound I lost felt like a victory, but I wanted more. I ran 10 miles daily. On rainy days, I followed Jane Fonda’s aerobics video. I only ate when I felt faint, choosing a handful of greens sans dressing and a piece of chicken the size of the space between my thumb and index finger. I even stole cigarettes from family members to use as a dessert. In just four months, I went from 180 pounds to 150 pounds on my six-foot frame. I was thrilled when I could track the blue-green veins inside my forearms like the lines of latitude on a map.”

Like Emillio, my experience revealed the complex interplay of cultural expectations and the insidious nature of eating disorders. In my working-class, primarily Hispanic community of Union City, New Jersey, anorexia was dismissed by my peers as a ‘rich girl’s disease,’ an attempt to ‘be white.’ Yet, the isolating pull of the disorder transcended race and class, offering a warped sense of belonging after years of bullying. My year-long stay in an eating disorder facility as a teen, a world of predominantly white, older teens, was a stark cultural shift. But I felt like I bonded with them more because of our status as anorexics than over our disparate economic statuses. In that shared vulnerability, we found a different way to be seen, loud and clear, in our struggle, even if it was within the confines of our illness.

Through years of therapy, I learned that recovery meant confronting not just the disorder but the harmful cultural messages about weight and food that permeated both my Cuban heritage and American upbringing. It was a painful lesson: eating disorders don’t discriminate, and the desire for control and acceptance can warp anyone’s perception of themselves.

For us both, the road to recovery has been a journey of unlearning, of dismantling the toxic narratives we learned from both American and Hispanic cultural messaging that had taken root in our minds.

But recovery is not a destination; it’s a continuous process. Our shared stories reflect a larger societal problem: a culture that still perpetuates unrealistic beauty standards and fails to acknowledge our natural bodies. We must challenge these narratives, not just for ourselves but for the generations of young Hispanic men and women who deserve to see their beauty reflected in the world around them, and to claim their space, loud and clear, without apology.

We need to create spaces where our bodies are celebrated, not condemned, and where our cultural traditions are embraced, not rejected. Where seeking help for mental health is seen as a strength, not a weakness. It’s about empowering every individual to be seen, truly seen, for who we are, with our unique voices.

While the ideal is to foster environments where cultural identity is celebrated, and mental health support is destigmatized, the data reveals a significant gap, particularly concerning eating disorders within the Hispanic community. Indeed, a 2022 report in the National Library of Medicine concluded, “Hispanic adults seek treatment less often than their non-Hispanic White counterparts across all eating disorder diagnoses, with about 14.6 percent of Hispanic adults who meet the criteria for anorexia nervosa, about 44.4 percent of those who meet the criteria of bulimia nervosa and 25.9 percent of those who meet the criteria for binge eating disorder seeking treatment.

We advocate for increased awareness for nutrition and education, emphasizing how to celebrate our vibrant cultures through healthier food preparation. This means exploring lighter alternatives to traditional heavy dishes without diluting our culinary heritage. For instance, I, Emillio, have created ‘California-Caribbean’ menus with revamped dishes like roasted chicken sofrito and air-fried empanadas, proving that cultural flavors can be rich in flavor yet healthy.

Crucially, we must also recognize the link between mental health and nutrition, according to Psychiatry Online, “…research suggests that individuals with psychiatric illness are more likely to have poor dietary patterns, disordered eating behaviors, and nutritional deficiency, contributing to both physical and mental health comorbidities.

It’s clear, then, that addressing both our mental health and our nutritional well-being, especially with the understanding that eating disorders don’t discriminate, is key to creating real change. Together, we can rewrite the story where our minds, bodies, and cultures are embraced, not erased. It’s time for our Latine community to be seen in all its complexity and resilience.

Carmen Cusido is a Cuban-American writer, communications professional, and adjunct professor based in northern New Jersey. And Emillio Mesa is a Dominican-American writer and events producer based in New York City.