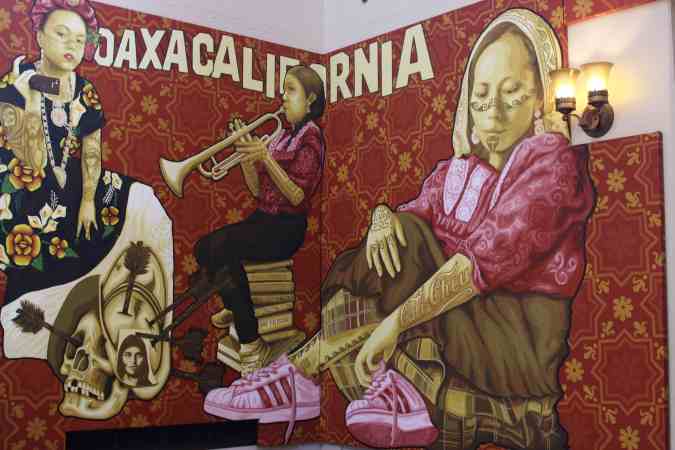

A young girl wearing a colorful embroidered dress, filigree gold necklaces, and a headpiece—all traditional Indigenous garments from Oaxaca— points an iPhone at the audience gazing up at her. With Chicano-style tattoos snaking up her arms, and the word “Oaxacalifornia” towering over her head, she’s the subject of one of eight large-scale murals in the rotunda of the Los Angeles Public Library. These paintings, which analyze the connection between Oaxaca and Los Angeles, defiantly challenge the voyeuristic gaze that commonly romanticizes Indigenous communities.

“Visualizing Language: Oaxaca in L.A.,” is one of the far-reaching series of exhibits and performances that make up Pacific Standard Time LA/LA, a massive celebration of the connection between Latin America and Los Angeles. The Library commissioned the works from Dario Canul and Cosijoesa Cerna, members of the Oaxacan street artist collective Tlacolulokos. To create the pieces, the artists walked the streets of L.A. for inspiration, and noticed the strong nostalgia Oaxacans in the United States felt for their place of origin. They were already well versed in the dialogue between the two places, due to the history of heavy migration to and from Los Angeles and Oaxaca. Mexican-American symbols travel south while Indigenous traditions travel north.

The murals explore the migration legacy of Zapotec people from Oaxaca, which began with the Bracero program and continued into the 1980s due to devaluation of the Mexican peso. Los Angeles is the city with the most Oaxacans outside of Oaxaca City, and Zapotecs make up the largest Mexican Indigenous population in this west coast city. Often times, the migrants crossing the border don’t speak Spanish, let alone English. They arrive needing to learn two new languages in order to navigate jobs with Spanish speaking co-workers, who often make fun of their Indigenous culture.

A strong sense of community, a tradition of gifting and collectivity called ‘Guelaguetza,’ and the harsh circumstances of migration, lead Oaxacans in Los Angeles to create enclaves that preserve their cultural traditions on a larger scale than migrants from other parts of Mexico. This is also why Oaxacan restaurants were among the first in the city to provide regionally specific cuisine from Mexico.

“That sense of tradition and that sense of dedication to the place where you’re from is visible here in L.A., where Zapotecs have used those same organizational systems to overcome the challenges and the difficulties of migration,” explains Dr. Xochitl Flores-Marcial, an expert on Zapotec culture and a consultant on this project. “How do you arrive in a city without a dollar in your pocket and are able to survive? It’s because someone says, ‘I’ll give you a Guelaguetza, I’ll give you a place to stay.’”

Yet, despite this preservation of tradition, culture is not fixed or stable – and the “Visualizing Language” murals convey this evolution. The works create a dialogue about the contributions of Zapotecs in L.A. and depict an Indigenous community that’s not idealized or static. “One of the main principles of Tlacolulokos is to avoid idealizing ourselves and avoid idealizing Oaxacans. The construction of our identity is always in flux,” explains Dario Camul, a member of the collective, at a recent talk held in the library. Through symbols like tattoos, 40z bottles, and brands like the L.A. Dodgers or Adidas, we see the story of migration.

Mexican-American symbols travel south while Indigenous traditions travel north.

Where Indigenous culture may be preserved through cuisine, values, and traditions, Western influence and Mexican-American culture is also present in these communities on both sides of the border.

While Oaxacan immigrants tend to preserve their culture, appropriating these symbols is a form of survival when faced with the isolation of being in a foreign place. In one mural, we see a woman full of tattoos with Indigenous garments sitting in front of street signs spelling out the names of various Oaxacan enclaves in L.A. like “Oaxakoreatown” and “Santa Monica 13.” Above the neighborhood nicknames, the sentence “A place as big as your suffering” welcomes you to what the city can represent to immigrants. “The murals talk about the challenges of migration, how people cope with those challenges, who embraces you, who protects you, how do you protect yourself,” explains Dr. Flores.

Yet, these murals are not specific to Los Angeles. There is a dialogue created between both places when immigrants in Los Angeles return to Oaxaca and take these new symbols along with them. A new kind of syncretism is created when Mexican-American culture collides with Indigenous Oaxacan culture.

A new kind of syncretism is created when Mexican-American culture collides with Indigenous Oaxacan culture.

“What you see in the murals isn’t just a reflection of Oaxacans in L.A., these same murals could be absolutely understood by people who have never left their pueblos in Indigenous communities in Oaxaca,” says Dr. Flores. “They go back to pueblos with the Adidas, with the L.A. hats, with the t-shirts, with the dickie pants or with iPhones. And those symbols tell a story of their migration experience.”

The paintings in the rotunda are in direct conversation with an existing mural above them depicting the colonization of Los Angeles. In this mural, painted in 1933, Indigenous peoples are depicted as docile and naïve, while European priests and conquerors tower over them. In turn, the new murals challenge this story and are created for and by Indigenous peoples who can see themselves and their experiences reflected in a complex way. “We are telling our history within the context of the murals that already existed. The murals talk to people like us who don’t have formal training but who have similar visual codes,” says Canul, one of the muralists. “We are putting Tlacolula on the map.”

When standing in the middle of the Library’s rotunda the murals envelop the viewer in this story of migration about an Indigenous community that is often overlooked. When looking at these massive works of art in unison, words above each of the eight murals come together to spell out “For the Pride of Your Hometown, The Way of the Elders, And in the Memory of the Forgotten” in Zapotec.

Whether it be through symbolism depicting the cultural exchange of Oaxaca and Los Angeles, or through the use of Zapotec language in the murals themselves, dialogue is central to these pieces. The murals depict the conversation between small towns in the southern Mexican state and the sprawling urban American metropolis, a conversation that won’t end with a wall.

The murals will be on display at the Los Angeles Public Library through the end of January. In addition, a catalogue featuring the artwork along with essays and poetry is available for purchase for those not in the city.