It’s no secret that Latinos are virtually absent from Hollywood. The annual diversity reports written by researchers at UCLA and USC make that very clear. Yet, high-profile Oscar wins by Mexican directors have clouded the landscape and have left audiences with the perception that Latinos are thriving behind the camera. It’s simply not the case.

The problem starts with our use of terminology and ends with how the data in these yearly studies is presented. If we are more precise with our language — like using the term Latino to only mean those who are of Latin American descent and born in the U.S. — then some lopsided patterns become evident.

On Monday, Stacy L. Smith of USC Annenberg’s Inclusion Initiative released a report, copresented by the National Association of Latino Independent Producers and Wise Entertainment. Entitled “Latinos in Film,” it analyzes Latino representation in Hollywood across various sectors: acting, directing, producing, casting and others. The results, though, muddied the waters.

The study’s authors reveal in a small-print footnote that “the term ‘Latino’ is used to refer to individuals from the Hispanic and/or Latino community.” In practice, this means data on Spanish and Latin American immigrants is mixed together with those born in this country.

This choice is a problematic one. Frances Negrón-Muntaner, a Columbia University scholar and author of “The Latino Media Gap” (a report commissioned by NALIP in 2014), explained in an email interview, “When you include people born and raised in Latin America who migrate to the U.S. as professionals and you also include Europeans, your data will not be able to account for the challenges that U.S. Latinos face, or grasp the relationship of U.S. Latinos to the media industries.”

Outlining the particular obstacles that U.S.-born Latinos come up against in the entertainment industry is a lengthy discussion, but one that can be summarized by two words: race and class. Foreign-born Latin Americans and Spaniards who have found success in Hollywood tend to be white and come from upper-class backgrounds. While there are directors who fall outside of these narrow confines, there are far more who do not. This is not to say they don’t deserve the accolades. Filmmakers from Latin America and Spain rely on their talent and creativity to garner awards and rack up box office receipts, but they have some extra help getting there. Regardless of what the specific advantages that propel foreign-born directors into a fruitful career are, diving into the data makes their hidden privilege more apparent. The proof is in the numbers.

USC’s recent report “Latinos in Film” paints a dismal picture: When looking at the top 100 films per year (in terms of domestic box office) between 2007 and 2018, “only 4% or 49 of these top jobs were filled by Latino helmers.” All of the groups encompassed under the Latino moniker in the study are egregiously underrepresented, but it’s even worse for second-generation Latinx.

In order to uncover how dire the situation is for U.S. Latinos in particular, I requested the list of movie titles and director names from Smith. Citing confidentiality reasons, USC’s list was not made available to me but using hints from the report, together with Box Office Mojo’s yearly summaries and data provided by UCLA’s Hollywood Diversity Report, I was able to mostly reconstruct the small data set on directors.

As the report notes, the 49 directing jobs are held by 28 unique individuals (since some of them appear several times with different movies). Dividing these directors into separate categories based on my reconstruction of the data, the breakdown is as follows: eight are U.S.-born and of Latin American descent (this includes Miguel Arteta who was born in Puerto Rico), one is of Spanish descent, 10 are from Latin America, and about eight are born in Spain. (Not included in my count is Daniel Espinosa, the Swedish-born director of Life whose parents are Chilean exiles.)

Comparing these numbers to U.S. Census data illuminates what the USC study obscures. Pew Hispanic reports that around 18% of the total population residing in the 50 states is Hispanic or Latino, with more than half identified as U.S. born. Less than one million people living in the U.S. are of Spanish origin, making them a little more than 1% of the Hispanic/Latino population. This is in stark contrast to what’s revealed when taking a deeper look at the data on directors.

When you split each group by birth and descent, the divide is staggering. While those who are U.S.-born of Latin American descent make up 64% of the overall Hispanic/Latino population, they are only 29% of the directors coded as “Latino” in the USC study.

On the flip side, those who are Spanish born absolutely overindex. They only account for 0.2% of the U.S.’ Hispanic/Latino community, but by coming in at 29% of the directors in the study, they occupy an equal portion of the list as U.S.-born Latinos. And while it’s not as wide a gap, those who are U.S.-born of Spanish descent make up 1.2% of the census’ Hispanic or Latino category and 3% of the directors in the report.

Similarly, the numbers almost match up for foreign-born Latin Americans. They are 34% of the Hispanic/Latino population and 36% of the director’s mentioned in Smith’s study. Reinterpreting the data in this way provides concrete evidence that U.S.-born Latinos are the only demographic that’s vastly underrepresented inside of the larger group that’s labeled as Latino in USC’s report.

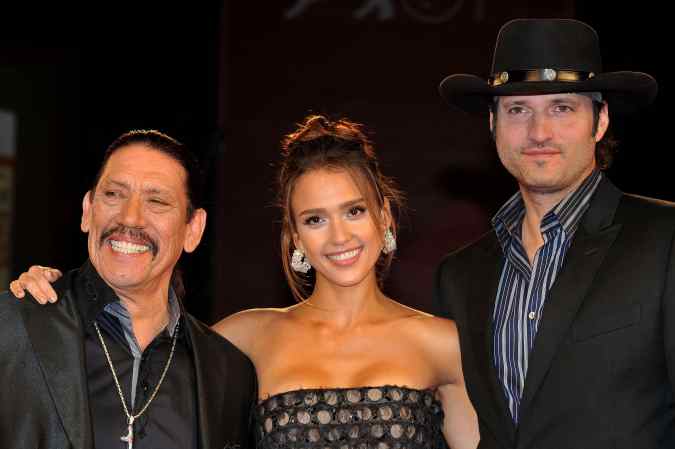

The facts are indisputable: Foreign-born Europeans and Latin Americans have an undeniable advantage in landing directing jobs of Hollywood big-budget features. Despite the odds, a handful of U.S. Latinos did overcome these challenges. Identifying them by name is certainly in order: Adrian Molina, co-director of Coco; Chris and Paul Weitz (Mexican actress Lupita Tovar’s grandsons); Michael Cuesta (American Assassin); Miguel Arteta; Oscar winner Phil Lord (with four different films); Steven Caple Jr. and, of course, Robert Rodriguez (Grindhouse, Machete and Spy Kids 4).

It’s also important to consider that Latinidad remains complex and racial hierarchies always come into play. Half of the U.S. directors are multiracial, with most of those having Caucasian heritage. It can’t be ignored that white Latinos of all nationalities are far more likely to be afforded a seat at the table. Steven Caple Jr., the director of Creed II, is one of four black filmmakers to helm a movie that grossed more than $100 million domestically in 2018. Yet, he’s the only Afro-Latino director who qualified for inclusion in the USC “Latinos in Film” study.

Also disheartening: No U.S.-born Latinas directed a feature that made it to the top box office spots in the 12 years this report covers. The only female helmer who made the list is Patricia Riggen, the Mexican-born director of 2016’s Miracles From Heaven, which ranked at No. 52 in the year of its theatrical release.

What remains clear — no matter how you interpret the numbers — is there’s still much work to be done to achieve parity for all Latinos in the film industry. But diversity programs should be reassessed to ensure they don’t inadvertently widen the gap between U.S. Latinx and those born outside the country under the guise of increasing Latino representation. For future reports, disaggregating data on diversity by place of birth is also essential to accurately tracking their progress.

Negrón-Muntaner further argues, “Separating the categories gives a better idea of how U.S. Latinos have different access and value in the media industry internally and in relation to other groups; a collapsed category may help those already in Hollywood make the case that they need more opportunities.”