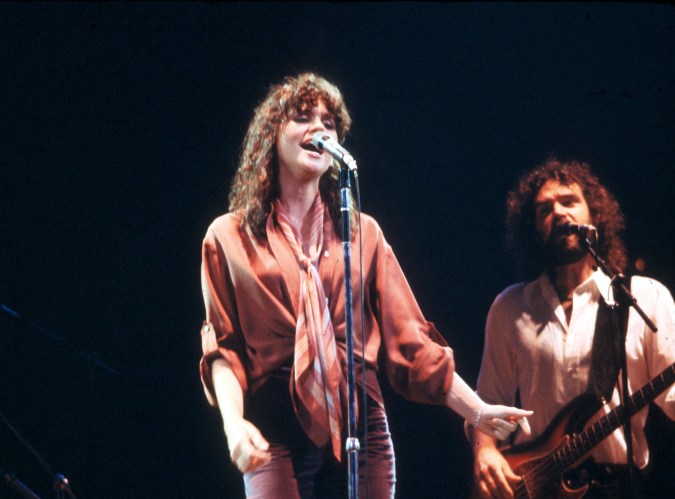

If music-lovers only know iconic singer Linda Ronstadt for her hit songs like “You’re No Good” or “Blue Bayou,” they’re missing out on some of the most incredible music the multiple Grammy Award winner has performed in her life.

In the new documentary Linda and the Mockingbirds, Ronstadt’s love for Mexican music is amplified by the relationship she’s nurtured over the years with Los Cenzontles (The Mockingbirds), a young Mexican-American song and dance troupe based in San Pablo, California.

In the film, Ronstadt, who is of Mexican ancestry on her father’s side, takes a road trip with the group to the small town of Banámichi in the Mexican state of Sonora, where Ronstadt’s grandfather grew up. In 1987, Ronstadt released Canciones de Mi Padre (Songs of My Father), an album of traditional Mexican folk songs. Today, it is reportedly still the best-selling non-English-language album in U.S. music history.

If you’re really doing it right, you’re not doing it for prizes.

In an interview with Remezcla, Ronstadt, 74, tells us about her memories of Spanish-language music as a child, why she’s always felt connected to her Mexican roots and more.

Linda and the Mockingbirds is available on VOD platforms.

This documentary focuses on the ensemble that you’ve been a patron of for decades (Los Cenzontles Cultural Arts Academy). Why is it important to you to be a spokesperson for them?

I think everybody needs to know where they came from and who they are. I think that in addition to learning culture in a group like Los Cenzontles, you learn basic music, art and dance instruction. It’s really important for us to express ourselves in an artistic manner, so we can identify our feelings and discover things we didn’t know about ourselves. It’s important for children to learn that if you know a performance art, you don’t have to be a trained seal. You can learn it by socializing and expressing yourself.

What is your earliest memory as a child of singing in Spanish?

There’s a song called “La Burrita” about a little donkey that I learned from [Father of Chicano Music] Lalo Guerrero. He was a friend of my dad. When I was two, he taught me that song. [Lalo and Los Lobos] made a record with Los Cenzontles called “Papa’s Dream” (in 1995), so they got to grow up with him, too.

Did you understand your biculturalism growing up?

I took my culture for granted, but we lived in the Sonoran Desert (in Arizona), which is on both sides of the border. It was wonderful. It was very easy to cross the border back in those days. You could go to Mexico for lunch and go shopping and visit friends or go to a baptism or wedding or quinceañera. There was a lot of socializing between families, so I felt connected.

The archived footage in the documentary of you singing in Spanish with Mariachi Vargas is so emotional. When you look back on those moments in your career, what did it mean for you to be able to use your platform to sing in Spanish and reveal to people the depth of your talent?

Well, I always thought that those songs were really good. I thought they were really classic. I always thought it was the best way to express myself. I always wanted to sing Mexican songs. I always had a hard time finding the right teachers to learn from. They didn’t know how to get a hold of Mariachi Vargas and they had never heard of me. Finally, we met at a mariachi conference in Tucson. So, I was really lucky that I got to have them because they’re the best.

Do you think Spanish-language musicians are known more today in the mainstream industry than they were back then?

It’s still surprising to me that a group like Los Tigres de Norte, who are the second most popular group after The Rolling Stones worldwide, are not known to most American audiences. It shows that the Latin culture is still largely invisible, especially Mexican culture. It’s disregarded.

Did you realize when you were recording Canciones de Mi Padre that it would make such a global impact?

I had no idea. I was just trying to do something I had been wanting to do since I was 18 years old. I was focused on that and not on whether it was going to be a success or not. When the record came out and we had the tour, I was worried.

You retired from singing in the last 10 years because of health issues. In the documentary, there is a scene where you’re watching a young performer singing and you’re mouthing the lyrics along with her. Have you found closure with the fact that you won’t perform again?

There’s nothing I can do about it except accept it. I can still sing inside my head. I can sing in a very tiny voice. I can still sing inside my brain.

I can still sing inside my head. I can sing in a very tiny voice.

If you could pick one word, what would you like your legacy to be?

I don’t know. I think I’ll leave that up to somebody else. Maybe “Eclecticmania.”

I’ve never heard that word before.

That’s because I made it up.

What did it mean to you when you were honored last year at the Kennedy Center for your lifetime of artistic achievements? You are now enshrined with performers like Ella Fitzgerald, Paul McCartney and Frank Sinatra, just to name a few.

If you’re really doing it right, you’re not doing it for prizes. But it’s always nice to know that you’re not working in a vacuum. I never expected to win a prize like that.