One of Luis Santeiro’s Emmy Awards sits on a living room side table, wearing a traditional Cuban guajiro hat. Santeiro has six in total, although his favorite, he tells us, is the Regional Emmy he won when he was just 30 years old for his work as head writer on the groundbreaking series ¿Qué Pasa, U.S.A.?

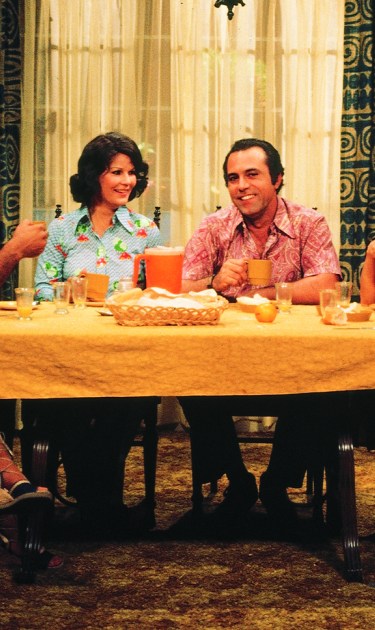

¿Qué Pasa, U.S.A.? holds the distinction of being the first bilingual sitcom to air on American television. It was produced from 1977-1980 by WPBT, Miami’s PBS affiliate. The show, which was geared toward Cuban-American teenagers struggling to balance cultural pride and assimilation while in exile, told the story of the Peña family. The Peña’s – stubborn head of the house Pepe, housewife-turned-working woman Juana, nostalgic abuelos Adela and Antonio, and increasingly Americanized children Joe (17) and Carmen (15) – were stand-ins for the Cuban experience in 1970s Miami. Caught between the more traditional cultural norms of their home country and the rapidly changing social landscape of the US, the Peñas have helped multiple generations of Miami-based Cubans and Latin American immigrants as a whole navigate their relationship to US society. Santeiro’s writing on the show, as well as the twenty years he has written for Sesame Street, have made him a pioneer of Latinx television.

During a recent interview, Santeiro talked about writing a bilingual and bicultural show, authenticity in Latinx television, and where he imagines the Peñas would be today.

This article was written by Kristie Soares and Miguel Nolla.

Authenticity Starts with Your Crew

¿Qué Pasa, U.S.A.? is often credited with being one of the most authentic representations of Latinx people aired on American television. Luis explained that the authenticity of the show started with the people who worked to create the series. “Everybody was from the community, the set designer, the cameramen, the costume designer, everybody.” Even the live studio audience represented the community, with tickets for the tapings being handed out in bodegas, local schools and businesses. For Luis, writing the specific situation of 1970s Miami was key, “I was living in Miami. Some people would say, ‘You were very young when you came from Cuba. How did you know us?’ They think I’m portraying Cuba, I said, ‘No, I’m portraying Miami. I’m portraying what I saw in Miami.’”

If You’re True to Your Story, Other People Will Relate to It

¿Qué Pasa, U.S.A.? has taken on a life far beyond its intended audience in Miami. After its first season, the show aired on PBS affiliates all over the U.S. and Puerto Rico. Its success soon extended past the traditional “bilingual markets,” and Luis said they received fan letters from all over the nation. He mused, “We would get letters from Nebraska. I’ve talked to Latin Americans, whether they’re from Colombia [or elsewhere], and they have somebody like that in their family.” For Luis, the message of navigating cultural conflict extends far past Miami. He remembers fans telling him, “I’m Jewish, but you know what? It’s cross cultural. The only thing that changes is the food on the paper plate. Latkes instead of empanadas.” He continues, “If you make it authentic, if it touches you, it doesn’t have to be your experience.”

People Will Laugh, Even if They Don’t 100 Percent Understand It

Forty years later, ¿Qué Pasa, U.S.A.?’s use of bilingualism has still never been replicated on American television. The sitcom was entirely bilingual, with many characters switching in and out of Spanish or English midway through sentences. Luis told us: “It was supposed to be 50/50. We would actually count. When we had a script, we had people count words then we would have monolingual readers, somebody who didn’t speak English and somebody who didn’t speak Spanish, to read it to see if they got lost.” Luis confessed that they usually ended up with a little more Spanish because when Manolo Villaverde and Ana Margarita Martínez Casado (who played Pepe and Juana) ad libbed lines, they’d default to Spanish. When we asked if he thought non-bilingual viewers were able to understand the jokes, he praised the actors’ use of physical comedy: “We went to the visual and the acting. You would lose some jokes if you didn’t speak both languages, but you didn’t lose the thrust.”

Never Underestimate the Power of Abuela

Inevitably our conversation turned to almost everyone’s favorite character, the grandmother Adela, who was played by Velia Martínez. Martínez had already had a very successful career in Cuba before going into exile in Miami, and was the most seasoned actress on the show. Luis reminisced about Martínez’s habit of ad libbing on set, often adding lines that she had heard her own mother say. “Oh no, my mother would say this,” he said, mimicking Martinez. “It was perfect. She was terrific. Oh my God, her timing was just incredible.”

On Latinx Representation on Television

We had to ask Luis his thoughts of Netflix’s One Day at a Time remake, in which the show’s creators reimagine Norman Lear’s 1970s sitcom in the context of a Cuban family living in Los Angeles. Luis remembers working with Lear in the ’80s when the two wrote a pilot together intended to be a spin-off of The Jeffersons, in which one of the characters goes down to Miami and invests in a bakery in Little Havana. Although the show was never made, Luis went on to write for Sesame Street, which he has done now for over 30 years, writing for iconic Latinx characters like Maria and puppets like Rosita. When we asked him about the state of Latinx television today, he bemoaned the fact that representations of Latinx people weren’t more specific to particular cultures. “They want to appeal to everybody,” he noted, going on to explain how trying to write pan-Latinx families often results in shows that don’t represent the reality of any specific community.

On Where the Peñas Would Be Today

Before we said goodbye, we asked Luis if he ever imagines where the Peña family would have ended up. He thought aloud: “Carmen might have married within the community and stayed closer to home. Joe would have probably married a friend of Sharon’s and he would probably be divorced. Carmen might have had not the best of marriages but she would probably stick with it and probably have two kids. Joe would probably have kids with two different wives. The parents would be pretty old by now, but still hanging around, still very much involved with the kids.”

You can watch full episodes of ¿Qué Pasa, U.S.A.? on the show’s website or PBS.org.