On March 31, 1995, the Tejana songstress simply known as Selena died of a gunshot wound in Corpus Christi, Texas. She was only 23 years old, but had already achieved what many artists fail to accomplish in a lifetime: she had album sales in the millions, several number one singles, multi-platinum records, and a handful of awards including a Grammy. For Latinos in the U.S. and across Latin America, Selena was a huge star; her Tex-Mex mashups of pop, cumbia, rancheras, and R&B were regularly heard blasting out of car radios, at weddings, and at quinceañeras. But for the rest of the United States, her music was virtually unknown.

All of that changed in 1997 with the release of a biopic about the late singer. The movie memorializing her life, Selena, is iconic in its own right. Starring Jennifer Lopez as Selena, Edward James Olmos as her father, and Lupe Ontiveros as her fan club president, Yolanda Saldívar, the film made tens of millions of dollars at the box office. More than just bringing people to theaters, it catapulted Selena’s music and story into the mainstream. Suddenly, everyone knew who she was. Selena fans went from being mostly Latino to a multihued rainbow of white, brown, and black. (Not to mention her legions of Filipina fans, a phenomenon I’ll leave for another article.)

Selena, the film, also launched Jennifer Lopez’s acting career. She was paid $1 million for the breakout role making her, at the time, the highest paid Latina actress in Hollywood. In an interview with Billboard, Lopez revealed that preparing to play Selena and performing in front of real live crowds as the singer inspired her to pursue her own music career, “It had a lot to do with it — all those performances. I sang in musicals before, but as part of a cast, never as a solo artist upfront or a recording artist. It made me realize, “Don’t neglect parts of yourself and let people put you in a box because you’re an actress. You can do this, and you can also do that.” Lopez’s turn as the Tejana star pushed her towards music and eventually propelled her to superstardom.

Serving as a platform to elevate both Selena’s music and J-Lo’s acting are big feats for a small (by Hollywood’s standards) film, but the lasting cultural impact of Selena goes even deeper. While Selena’s music articulated the particulars of living a bicultural Mexican-American experience in the United States (i.e. she sang in Spanish but didn’t speak it) to other Latinos, the movie took that same message to the masses. Its commercial success is explained by its simultaneous ability to speak to Latinos and non-Latinos alike. The production team behind the scenes of Selena, themselves bicultural Latinos, set out to do just that: to take a story that was deeply rooted in Tejano culture and transform it into something universal. Selena the film, just like the singer, was both Mexican and American at the same time. Add to that Selena’s pre-existing fan base and it’s not hard to figure out why it was a box office hit back in the nineties, spurred a special edition DVD release ten years later, and remains one of the most quoted Latino movies of all time.

While Selena’s music articulated the particulars of living a bicultural Mexican-American experience to other Latinos, the movie took that same message to the masses.

The last few scenes of Selena are soul-crushingly sad. There’s a close up of her hand as it goes limp in an ambulance racing towards the hospital and we hear a newscaster lament, “We mourn the loss of the popular singer.” Cut to an empty stage, the camera circles around a lonely microphone stand and Selena’s disembodied voice begins to croon, “Late at night when all the world is sleeping, I stay up and think of you…”

What makes those final moments so hard to stomach is that we’ve just spent two hours watching Selena and her family struggle to pay the bills, and then finally skyrocket to the top of the Latin charts. Her biggest dream, an English-language crossover, is within reach when suddenly everything is snatched away.

As her posthumous hit single “Dreaming of You” — the last song she’d ever record at her father’s studio — plays, we see a doctor break the news to her family. There’s no sound, we can’t hear what the doctor is saying but their sobbing is enough. We know Selena didn’t make it.

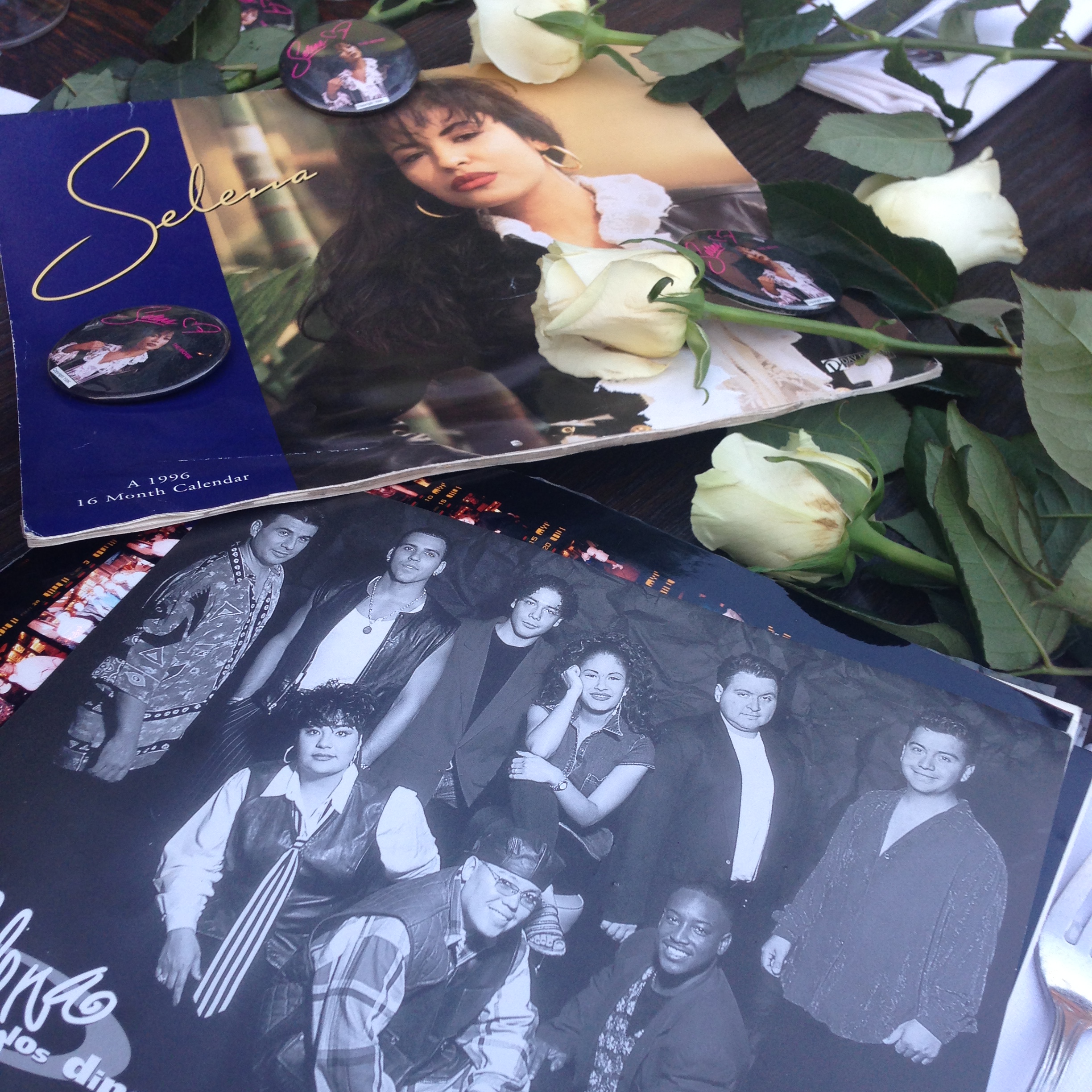

The chorus kicks in, ushering in the movie’s final sequence: a somber vigil where hundreds of her fans have gathered. They hold flickering candles, roses, airbrushed pictures of Selena, and glittery signs pledging their love for her. If you look closely right after the memorial starts, there’s a close up of a forlorn young girl. She has long dark hair, is holding a white taper candle in her hand and, like the other extras in the scene, was a fan of the “Queen of Tejano” in real life. Her name is Tonantzin Esparza and it’s likely this movie wouldn’t have happened without her.

Tonantzin’s father, Moctesuma Esparza, is a movie producer. By the late nineties he had established himself as a force in Hollywood, having pushed forward big projects like The Milagro Beanfield War (directed by Robert Redford and starring Ruben Blades), The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez, and Gettysburg, a civil war epic starring Tom Berenger and Martin Sheen that had a $25 million budget.

Although much of his career was focused on Chicano stories, Esparza didn’t know a lot about Selena. His teenage daughter, on the other hand, was a devoted fan. Selena’s death made such an impact on Tonantzin that reflecting on it twenty years later still brings her to tears, “I remember the day. I was very upset. It was just really, really sad for me. I remember telling both my parents and all my friends that she died. My dad knew who she was, but it’s not like he was a fan like I was.”

Within a few days, Tonantzin decided that her father should be the one to take Selena’s life story to the big screen, “In that week to come, I remember telling him: ‘You should do a film about her.’ And he was like, ‘Oh, no.’ Right away he was like, ‘Absolutely not. I wouldn’t want to be part of any opportunistic or sensational story about such a horrible tragedy.”

Moctesuma was concerned that it was too soon to tell a respectful story about the singer, “My sense was that Hollywood would be interested in the crime story and the murder of Selena, and I wasn’t interested in that kind of story.” But Tonantzin, like most teenage girls, was incredibly insistent, “I just remember as the news kept ensuing, I kept talking to my dad, and I kept saying, ‘You have to! You have to!’ I was kind of really bugging him. And I said, ‘Of all people to do it, you would do it with heart. You would do it as a celebration.”

Even as a high-schooler, precocious Tonantzin knew that plenty of money-hungry producers would be eager to jump on a project that had a proven, built-in audience. But as a young Chicana who connected to Selena’s bicultural upbringing, she worried that the others might miss the mark, “I was very adamant that I wanted him do it because he is Mexican-American and he would have the right sensibility to tell her story correctly and to give it that heart.”

Over a period of many months, Tonantzin gave her father CDs to listen to and documentaries to watch hoping to drive home just how important “La Reina del Tex-Mex” was to her generation. “I kept telling him, ‘Look how much she influenced me. She was like a role model for me, [look at] what she represents.’ He just kept saying, ‘No, I don’t want to be part of that. I don’t want people to think I’m trying to take advantage of her death to make money, or to take that kind of opportunity.”

Finally, after reading a biography that was published right after her death, a lightbulb went off for Moctesuma: “I saw that the family was the driving force behind the success of Selena. Her brother, her sister, her father, her mother, had been touring and making music since she was a little girl, and building on the history of her father Abraham, who had had a band when he was a teenager.” The story of the Quintanilla family was the story of the American Dream, of people who confronted racism with determination and reached success on their own terms. This was a story that could do Selena justice — and a way to stay true to his mission of making movies that broke with Hollywood’s stereotypical representation of Latinos.

With a clear idea of the kind of movie he wanted to make, Moctesuma reached out to Selena’s father, Abraham Quintanilla, “I wrote Abraham a letter letting him know that I was interested in talking to him. I had no idea what was going on with anyone wanting to make a movie about it, but I had heard in the news that people had been talking about it. Abraham received my letter, one of his staff people gave it to him, and he invited me to come out to Corpus Christi.”

When Moctesuma went to Texas to meet with Selena’s family he discovered that over a dozen producers had already approached Abraham, seeking the rights to make a movie. Even worse, it looked like one of those other deals might go through, “He was already, in fact, in negotiations and there were draft agreements that were going back and forth with another producer.”

Back in Los Angeles, when he broke the news to Tonantzin, she didn’t take it well, “I was like, ‘How could you have not gone earlier?’ I can be pretty hard on my dad, so I was like, ‘You lost it! It could have been your film! You could have done it! Only you!”

Moctesuma though, still had a glimmer of hope. With several productions under his belt and a deep knowledge of Hollywood’s complicated contracts and negotiation process, he offered himself up as a consultant for Abraham Quintanilla, to help him navigate the process of finalizing an agreement with whichever producer he chose. As time went by, the two men got to know each other better; they became close associates, and as fate would have it the other deals stalled. Moctesuma took a shot in the dark and made a proposal to Abraham, something that no other producer had offered, “I made him a proposal that we be partners, that I would work with him, and together we would create a story that presented the life of the family and Selena that would honor her memory, her life, and her achievements.”

“I made him a proposal that we be partners, that I would work with him, and together we would create a story that presented the life of the family and Selena that would honor her memory, her life, and her achievements.”

It was a contract that a major studio would never agree to but Moctesuma took the gamble, “I agreed with Abraham that he would have the right of approval of the actress who played Selena, and who played him, and of the director and the script. It’s completely unheard of in Hollywood, to give participation to the actual people in the true story and the approval rights.” Abraham likely knew no one else would offer him creative control of the movie and signed a deal with Moctesuma’s company, Esparza/Katz Productions.

Abraham Quintanilla realized what Tonantzin had known all along, that her dad was the right person to tell Selena’s story and that only Moctesuma could put together the right team to make this movie. “I was so convinced that only my dad would be able to put this together in the right way. Because no other producer really existed at that time that had such a body of work and that cultural commitment of telling Mexican-American stories, of knowing that struggle, what it is to not be fully Mexican and not be fully American. He knew what that tension meant and how to make sure to choose the right director who would also put that element in.”

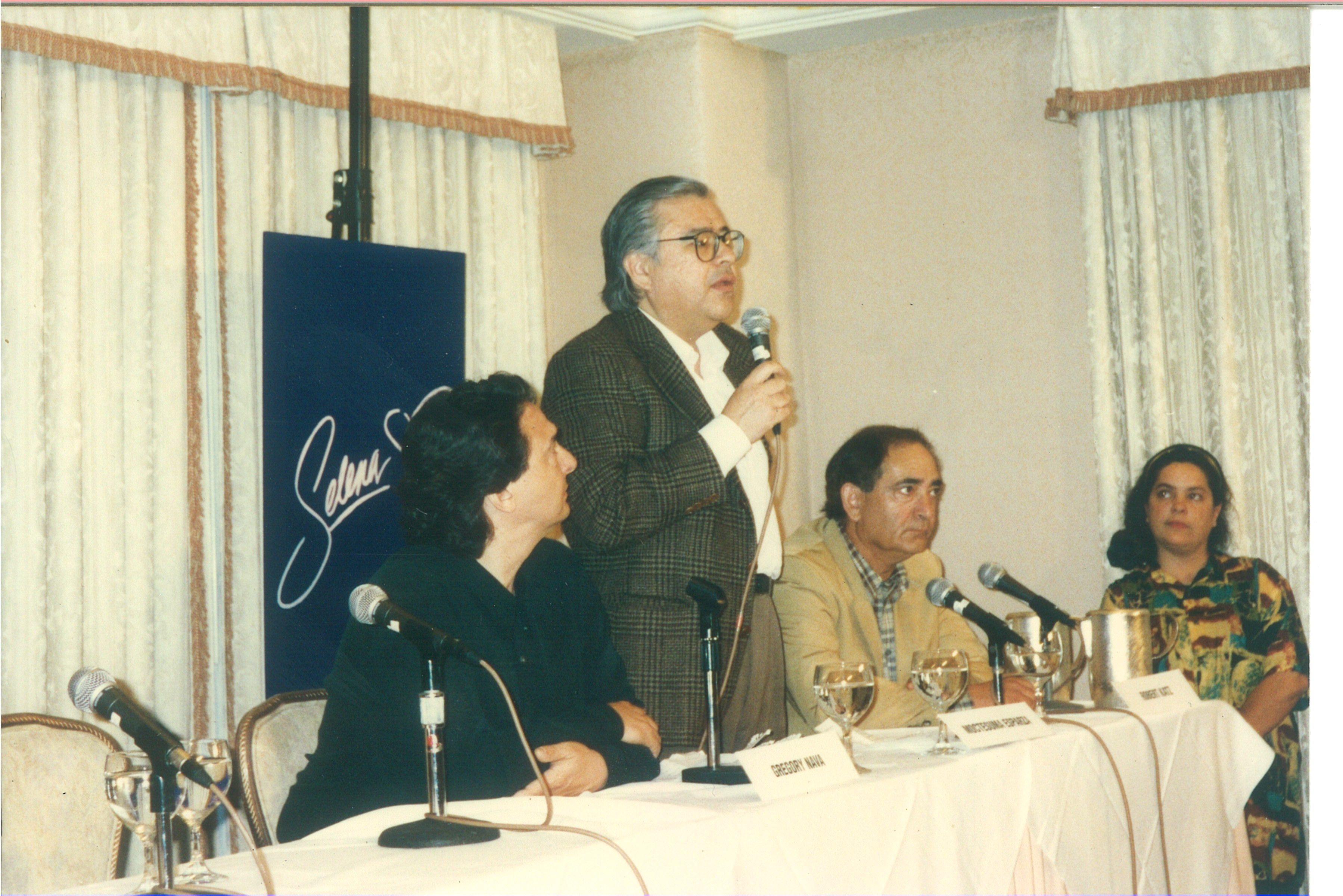

Moctesuma talked to Abraham and suggested Gregory Nava as a director. It turns out Nava had been attached to one of the other failed deals, and though Abraham was not a big fan, Moctesuma pushed him to agree. He knew Gregory well (they had gone to college together at UCLA) and felt he had the right sensibility. Abraham finally relented.

With a director secured and a detailed treatment of the plot written, Moctesuma went in search of funding for the film. It is notoriously hard to get investors to hand over money for a project involving an all-Latino cast. Movie studios are not risk-takers, they dump cash into franchises and sequels that are guaranteed to make their money back and — with only a few exceptions — Latino films don’t draw big audiences to theaters. What Moctesuma had on his side though, were Selena’s fans and the millions of records they had bought. He explains, “There was already a demonstrated, proven audience for the movie, which is what any studio executive would care about.” He got the $20 million budget secured in no time, “Warner Brothers put up 100% of the money and it was the fastest, easiest financing of a movie of my career.”

Next, they went in search of an actress to play Selena. Open casting calls were held in 5 cities: New York, Chicago, Miami, San Antonio, and Los Angeles, and in total 80,000 young Latinas showed up for a chance to play Selena. When it was announced that Jennifer Lopez, a Nuyorican actress, would play the Tejana singer, Moctesuma, a lifelong Chicano activist had brown berets picketing outside his office. Moctesuma invited them to speak to him, he listened to their concerns, and as a former brown beret himself explained the choice: that she was the best person for the part. Eventually, the controversy died down.

This deep resonance with Selena’s straddling of two cultures, that feeling of being “ni de aquí, ni de allá” is why Tonantzin was adamant that her dad be the one to bring this movie to fruition.

With the cast decided and the production about to start Moctesuma offered his daugher, Tonantzin, a chance to work on the set as an assistant in the makeup department. “My dad talked to me and said, ‘Would you want to come live with me in San Antonio and work on the movie? Because if it wasn’t for you I wouldn’t have done this movie.” Tonantzin jumped at the chance, taking time off school to work in the makeup trailer, a hub for gossip and glimpses into the inner workings of a film set. She remembers getting up at three in the morning to work on aging Constance Marie, the actress who played Selena’s mother but who was, in reality, only a few years older than Jennifer Lopez. Tonantzin had to push and pull at Constance Marie’s face to make it look like she had wrinkles, “The process took a couple of hours. She used to joke, ‘Ow! You’re pulling too hard,’ or, ‘You’re gonna make me a real vieja!’ Because we were like abusing her face every morning, stretching it out.”

When it came time to film the final scene where Selena’s fans mourn her death, Gregory Nava — the director and close friend of her father — asked Tonantzin to be in it, knowing how meaningful that would be for her. To find additional extras for the scene, the production team put up fliers around Selena’s hometown asking fans to come out and be part of the shoot. It was hours of commitment but the crowds came anyway and brought their own signs, memorabilia, and candles. Tonantzin remembers that the mood on set was somber, “It was silent part of the time and then they played some of her music. It was a very large crowd that night and everyone was just remembering Selena. People were quiet, but it was very emotional because it was all of her fans. It was like a real vigil and they just filmed it.”

For most Latina fans of Selena, Tonantzin included, her music tapped into something that mainstream music and media ignored. “Our household was very bicultural. My dad grew up speaking Spanish but not my mom. I was very American, yet my dad really wanted to instill a lot of culture in us, and so I’ve always been on this edge of I’m American, but I want to be proud of being Mexican. And in the media, or in music, there really wasn’t anybody else doing that. I just really connected to who she was as a young woman, as a woman who was both Mexican and American, and really putting our culture and music on a national, even international level. And she looked like me, she had dark skin and long brown hair. I think I saw myself in her. I was aware that she didn’t speak Spanish, that she was singing in Spanish but she didn’t really speak it. I must have listened to interviews with her in English, and that’s why I think that more than other musicians that I heard on Spanish-language radio, she stood out to me, because there was that connection of, she’s like me.”

This deep resonance with Selena’s straddling of two cultures, that feeling of being “ni de aquí, ni de allá” is why Tonantzin was so adamant that her dad be the one to bring the Selena movie to fruition. She knew he could find a way to share with the world what is was like to be both Mexican and American. In turn, as a producer Moctesuma Esparza turned to his friend, Gregory Nava, and placed the job of writing and directing a script that could get this idea across squarely in his hands.

Gregory took great care with the task given to him. He went to Texas, spent time with Selena’s family and husband Chris, and listened to their stories. When he finally put her life story into words, he mixed in his own lived experience as an American of Mexican descent and ended up writing a line of dialogue that is the single most succinct and spot-on explanation of what it’s like to be Mexican-American in the United States.

The actor Edward James Olmos, as Selena’s father says to his kids, “We gotta prove to the Mexicans how Mexican we are, and we gotta prove to the Americans how American we are, we gotta be more Mexican than the Mexicans and more American than the Americans, both at the same time. It’s exhausting. Damn. Nobody knows how tough it is to be a Mexican-American.”

It was a piece a dialogue that struck a chord across the Latino community and remains one of the most quoted lines from the Selena movie, almost twenty years after its release. For Moctesuma, it hit home too, “I think that it was emblematic of the existential challenge of being a Chicano in the United States, and Gregory Nava wrote that, to his credit. He had the challenge of being able to externalize what we all live. Gregory lived that, too. We all live that challenge.”

When I asked Tonantzin about her favorite lines from the movie, she picked the same one (like father, like daughter), “Eddie Olmos is so good in that scene. And I think that the scene is funny, the way he did it. It was so well done. Because it wasn’t didactic, it wasn’t preaching. They did it so naturally that, yeah, I do connect with that, because it’s true. And maybe [the character] Abraham experienced it more with the discrimination he faced and the barriers and his unfulfilled dream of being a musician. Not being able to get the Mexicans or the Americans to accept him. But really, it’s true. Those barriers did exist in Mexico and in the U.S., and Selena pushed past them. And those barriers still exist.”

Ultimately, that’s why Selena endures, its cultural impact is as relevant today as it was back in the nineties when it hit theaters. It’s still really hard to be Mexican-American (or any type of hyphenated American). Selena, as a bicultural Latina who spoke English with a Texas twang and struggled with her pocha Spanglish reached millions singing in Spanish. Something about her songs, together with her fashion sense, dynamic performance style, and down-home personality made her fans feel like she was speaking directly to them. But, without a crossover album in English her influence remained relegated to a Latino-only audience.

Tonantzin Esparza was one of those fans who felt personally touched by her music. Selena was and remains one of the few voices in the music world that she could relate to. It was this deep, personal kinship she felt when listening to her favorite songs like “Si una vez,” “Como la flor,” and “El chico del apartamento 512″ that pushed her to convince her dad to make a movie about her idol. In an almost viral chain of events, Selena sang songs that simultaneously reached the individual hearts of millions of Latino fans — and then one of those fans, Tonantzin, turned her personal love for Selena into a crusade to make a movie about her. Selena the film, in turn, took Selena’s music with its bicultural message and aesthetic to many millions more.

There aren’t many movies out there that perfectly encapsulate the challenges of living between two cultures. Hopefully, it won’t take several decades for the next one to be made. In the meantime, I’ll be re-watching Selena because, “Anything for Selenas.”