Indigenous cuisine in Latin America has been around for centuries, and a select few chefs are working to keep their traditional recipes alive. Inspired by their surrounding produce, these nutritiously dense recipes are literally rooted in the origin stories of their respective land. The natural evolution of their cuisines and the introduction of new ingredients have kept these Indigenous recipes in the hands of smaller communities, including the chefs featured on this list.

Here, they discuss their cuisine’s importance and value and share a few recipes for Indigenous comfort food. They also emphasize the importance of preservation, dangers of appropriation and more.

Chef Denise Vallejo, Founder of Alchemy Organica

Chef Denise Vallejo’s mobile kitchen in Los Angeles, Alchemy Organica, is focused on Indigenous, plant-based Mexican cuisine.

“If I’m recreating a traditional, post-invasion Mexican dish, my goal is always to ‘re-indigenize’ the recipe by using more Native foods,” she tells Remezcla. “A good rule of thumb is that ‘anything that grows together, goes together.’ We have a powerful agricultural history with the milpa (field) farming technologies growing things like beans, avocados, squash, chilies & corn together in symbiosis. Of course, all those foods taste amazing together. They are environmentally & nutritionally harmonious.”

A good rule of thumb is that ‘anything that grows together, goes together.’

The magical transformation (alchemy) of her ingredients into meals is evident through her use of activated charcoal, for example, which not only colors the food naturally but also detoxifies and can help heal the body as well, according to Vallejo. “Because of my background in the Occult and Metaphysical Sciences, most of my recipes come together through concepts I’m trying to express. I look for the proper corresponding native ingredients that express those ideas.” Her favorite ingredient to cook with is corn as she says it’s the foundation of almost every good meal: “It represents who we are spiritually and physically. It’s everything. You’d have no tacos, no tamales, no pozole, no atole. Nothing without corn. Maiz is our legacy.”

Chef Claudia Serrato, Co-founder of Across Our Kitchen Tables

Claudia Serrato is a cultural and culinary anthropologist, an Indigenous plant-based chef, and a food justice activist scholar. Across Our Kitchen Tables is a culinary resource and network hub for women of color. She says that, for her, there is no separation between Indigenous cuisine and plant-based foods because “at the end of the day, all the food flavors, sazón, and elements are earth-based,” she says. She attributes the rising popularity of Indigenous cuisine to the growing food consciousness in the mainstream but says that people need to understand that Indigenous food is medicine, not a fad.

Indigenous food is medicine, not a fad.

“My only true concern is that it becomes appropriated by non-Indigenous peoples as there has been a growing interest by them without truly understanding it within a cultural and sacred context. I call this food voyeurism, which is a great example of imperial nostalgia of a land-based foodway.”

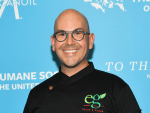

Chef Ricardo Zarate, Restaurateur and Cookbook Author

Ricardo Zarate ( known as the “Godfather of Peruvian Cuisine”) has opened several acclaimed restaurants in LA including Peruvian bistro Rosaliné. Zarate, who was born in Lima, published “The Fire of Peru: Recipes and Stories from My Peruvian Kitchen” in 2015. He explains that in order to understand Peruvian cuisine, it’s essential to understand how diverse it is—from the Incas to the influences of other cultures (e.g. Chinese and Japanese). He considers the ají amarillo the most important Indigenous ingredient because of its versatility: It can taste either spicy or floral depending on how it’s prepared. He values its “DNA” saying, “It comes from the Andes of Peru. Can you imagine Thai food without spiciness? Chilis came all the way from the Andes of South America to Asia, I just love cooking for that reason.”

These recipes shape cultural wealth.

Chef Noel Morales, Restaurateur and Cookbook Author

Noel Morales, with Aztec and Omec roots, runs a restaurant and mezcal bar, El Refugio Mezcaleria, in Todos Santos, Mexico along with wife Rachel Glueck. Earlier this year they published “The Native Mexican Kitchen: A Journey into Cuisine, Culture, and Mezcal” featuring centuries-old recipes. He believes conservation of Indigenous recipes is important for many reasons but more than anything else it’s because of the flavor.

“These recipes shape cultural wealth, if you use local ingredients you don’t need to bring in anything from someplace else,” he tells Remezcla. Morales adds that the recipes should be respected by being kept as close to the original as possible and dismisses those who appropriate Indigenous food at more high-end locales. When it comes to his own cooking he favors moles: “The flavor is like a good song and, since I don’t know how to sing, I eat mole. It has different nuances and tones, different levels of spice and fat, and that makes it interesting. It’s a joy for your palate for everything you encounter there.”

RECIPES

Atole de Piña/ Pineapple Atole (courtesy of Noel Morales):

This is an ancient drink made from corn. It is flavored in many different ways, but pineapple is one of the most common. Traditionally, one drinks atole with tamales.

5 cups water at room temperature

1½ pieces of piloncillo or 1½ cups of brown sugar

2 inches cinnamon stick

2 pounds fresh pineapple

1¼ cups corn flour

Optional: 1 cup condensed milk

1 pinch salt

½ cup baking soda

- Place 4 cups of water, the piloncillo (or sugar), and the cinnamon in a pot on medium and leave to heat for 10 minutes or until the sugar melts.

- Clean and cut the pineapple into 2-inch cubes. Put the pineapple and 1 cup of the cinnamon and sugar water into a blender and blend well. Strain through a metal strainer to remove any large pieces and add the rest of the cinnamon-sugar water. Heat and stir regularly for 8 to 10 minutes or until it boils.

- Place the cornflour and 1 cup of water into the blender and blend well. Strain and add to the pot with the pineapple, sugar, and cinnamon. Heat and stir constantly for 10 minutes.

- If you’d like to add the condensed milk, do so now. Heat and stir for another 3 minutes. Add the salt and baking soda and heat for 2 more minutes.

- Check the taste and add more sugar if necessary. Serve hot or cold.

Tlilxocolatolli Champurrado (courtesy of Denise Vallejo):

Tlilxocolatolli is “Black Chocolate Atole” in Nahuatl; Tliltic=black; Xocolatl=chocolate; Atolli=atole

The ancient Mexican and Maya cultures valued cacao which was almost exclusively consumed in beverage form for ceremonial or medicinal purposes. In this recipe, using blue corn masa harina with cacao and activated charcoal will give this ancestral beverage a much darker hue, while the morita chilies add more depth of flavor with hints of smoke & spice. Adding the amaranth flour increases the protein content making this drink much more filling and substantial. Drink with reverence.

4 cups filtered water + more water for soaking

1/2 cup raw cashews

1/2 cup + 2 tablespoons agave or maple syrup

1/4 cup blue corn masa harina

1/4 cup raw cacao powder

3 tablespoons amaranth flour

1 1/2 teaspoons activated charcoal

1 teaspoon ground Mexican cinnamon

1-2 dry morita chilies

2 teaspoons vanilla extract

1 tablespoon cacao butter or coconut oil

Pinch of salt

- In a medium bowl, place raw cashews & fill with enough water to cover the cashews. Cover bowl and place in the refrigerator. Allow to soak at least 2 hours or overnight. In a small pot, bring a cup of water to boil and add the dry morita chilies. Turn heat off and allow chilies to reconstitute for 15-20 minutes until softened. Set aside.

- Rinse and drain the raw cashews that have been soaked and place into a high speed blender. Add 4 cups of water, blend on high until creamy & smooth. Add the agave, blue corn masa harina, raw cacao powder, amaranth flour, activated charcoal, cinnamon, soaked chilies and salt to the blender and blend until thoroughly mixed. Pour the contents into a medium sized, heavy bottom pot and cook on the stove over medium low heat. Using a whisk or molinillo, froth the mixture until it begins to slightly thicken. Adjust the heat as necessary so the atole doesn’t burn. Add the vanilla and stir well. Taste and adjust for desired sweetness. Add more agave or maple to your liking. Stir in cacao butter or coconut oil until melted. This is optional but adds more richness to the beverage. Atole is ready to serve when it is hot and slightly thickened, about 10 minutes.

Simple Wild Rice con Leche (courtesy of Claudia Serrato):

1 cup of dry wild rice

1 cup of corn kernels

5 cups of water

⅛ tsp of vanilla

1 tbsp. of maple syrup

1 stick of cinnamon

- Place wild rice and cinnamon stick with 4 cups of water to cook for about 20-25 minutes.

- Place sweet corn kernels, vanilla, and maple syrup into a blender with 1 cup of water. Blend until completely liquified. Once wild rice is fluffy, spoon the desired serving amount onto the bowl and pour corn milk over. Top with desired nuts, dried fruits, and/or eat as is. Enjoy!

Peruvian Beef Stir-Fry with Red Onions, Tomatoes, Scallions & Cilantro (courtesy of Ricardo Zarate):

About 1 cup baby fingerlings or roughly chopped potatoes,

2 handfuls of homemade or good-quality frozen French fries, or about 1 ½ cups rice

8 to 10 ounces filet mignon or tenderloin, thinly sliced into 2-inch-long strips

Kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper

½ teaspoon pureed garlic

½ medium red onion, halved from stem to root end

1 ripe medium heirloom, beefsteak, or another juicy tomato

2 plum tomatoes

2 scallions

3 or 4 sprigs fresh cilantro

1½ tblsp. Saltado Sauce

1½ tblsp. soy sauce, preferably a good-quality Japanese brand, or more to taste

2 to 3 tblsp. canola or other vegetable oil

- Prepare the potatoes or rice, or rewarm the leftovers. You can roast baby fingerlings, go all-out and confit them in olive oil, make homemade french fries, or even fry up good quality store-bought fries. The same goes for rice: Use leftovers, or make your favorite style of white or brown rice to serve with the saltado.

- Next, prep all of your other ingredients, so they’re ready; this dish cooks quickly. (Keep each in a separate pile.) Sprinkle the beef lightly with the salt and pepper and rub the pureed garlic all over the meat with your hands. Put the red onion half, cut side down, lengthwise on a work surface. Slice off both ends, then slice the onion into lengthwise strips about ½ inch thick, moving the knife at a slight angle as you work around the onion globe. Your knife should be almost parallel to the cutting board along the sides of the onion and upright at the top. Cut the tomatoes in half lengthwise and cut each half into several large, chunky wedges. Finely chop the scallions, including about halfway up the green stalk, or chop them roughly for more texture, if you’d like. Finely chop the cilantro leaves and top half of the stems. Have your saltado and soy sauces measured and ready.

- Heat a wok or large sauté pan over high heat until hot—a good 2 minutes. Pour in the oil to lightly coat the bottom of the pan and heat the oil for 2 to 3 minutes, until very hot. The oil shouldn’t be smoking, but close to it. Swirl the oil around the pan, then toss in the beef and quickly sear both sides for a few seconds each until it begins to brown, about 30 seconds total. Add the onion and shake the pan or use tongs to flip them a few times, then add the tomatoes right away. Fry the saltado until the edges of the onions color in a few spots and the tomatoes barely begin to soften, about 30 seconds. The total cooking time shouldn’t be more than 90 seconds at this point.

- Immediately drizzle the saltado and soy sauces along the edges of the wok or pan, not on top of the stir-fry ingredients. You should smell the sauces caramelizing. Scatter the scallions and cilantro on top of the stir-fry and toss everything together one more time. Taste and add another drizzle of soy sauce, if you’d like. The saltado should be really juicy, with big flavors that the potatoes or rice can sop up.

- Spoon the lomo saltado straight out of the pan into serving bowls. Pile the potatoes on top or serve the rice alongside.