Lately I’ve found myself running into a lot more Venezuelan friends in places that aren’t, well, Venezuela. It’s no secret that the country is not in its best moment: we’ve all read the horror stories of long lines to buy essential goods at the market, of rampant crime and political instability. And not all of it is hyperbole. A friend of mine from Caracas recently moved to Mexico City because, he told me, Venezuela is now “unlivable.”

I spent the holidays with that friend, along with a group of other Venezuelan expats. It would have been a pretty unremarkable Saturday night hangout, with beers, music and a few herbs to soothe the holiday blues– were it not for his insistence on serving homemade hallacas, which, I learned, are the staple of any Venezuelan Christmas.

Funnily enough, I’d just been introduced to hallacas a few weeks prior at the home of chef Luis Herrera – or Luis Guayaba as he is sometimes known – and his wife Mariana Martín Capriles in Crown Heights, New York. Luis’s story isn’t at all like my friend’s. He didn’t flee Venezuela due to need or desperation (which is perhaps the first thing one might assume about a Venezuelan expat). In fact, one could say that Luis led a charmed youth, spending most of his childhood traveling back and forth between Europe and Caracas. For the better part of his twenties Herrera was a graffiti artist, until a twist of fate found him doing a 180-degree turn into the kitchen, where he discovered the appeal of his native cuisine. In retrospect, his career as a New York chef seems almost like a fluke.

Together with Mariana (who also performs under the moniker MPeach), Herrera has hosted El Brunch Gozón, a pop-up restaurant that doubles as a tropical bass party, for the past three summers. There, Herrera prepares a variety of Venezuelan specialties like cachapas, empanadas, cachito de jamón, ceviches, and desayuno criollo. It’s a low-key, Sunday hangover oasis of sorts, a true rarity that has been steadily gaining popularity over the years in both New York and Venezuela.

Becoming an ambassador of traditional Venezuelan dishes is an unexpected turn of events for Luis, considering he didn’t grow up eating much of his native cuisine. It was only during his formal studies at CEGA, the Center for Gastronomic Studies in Caracas, that he became acquainted with the Venezuelan culinary tradition.

Though most of his training is in his native country’s cuisine, Luis actually cooks Mexican food for a living. He is sous chef at Cosme, Enrique Olvera’s renowned Manhattan restaurant (voted best in the city by the New York Times in 2015). In this role, he’s found threads that connect the two cuisines – as he was quick to admit, hallacas are direct descendants of the tamal, though it is sort of taboo to point it out. (The difference is that hallacas are much more atascadas.) Of course, the recipe varies, but the full-blown affair includes everything from olives, to peppers, pickles and raisins, and more, depending on the maker’s tastes. The story goes that the dish originated from slaves, who’d take all the leftovers in the kitchen and concoct a dish from them.

The evening I visited them, the couple was preparing a batch of a little over 70 hallacas, which naturally extends the amount of time required to prepare them. As they are the cornerstones of any holiday meal in Venezuela, it is customary to prepare a batch to hand out to friends and family several days before Christmas. Conveniently, their enveloped quality makes them easy to store. If frozen, the meal can last for several months.

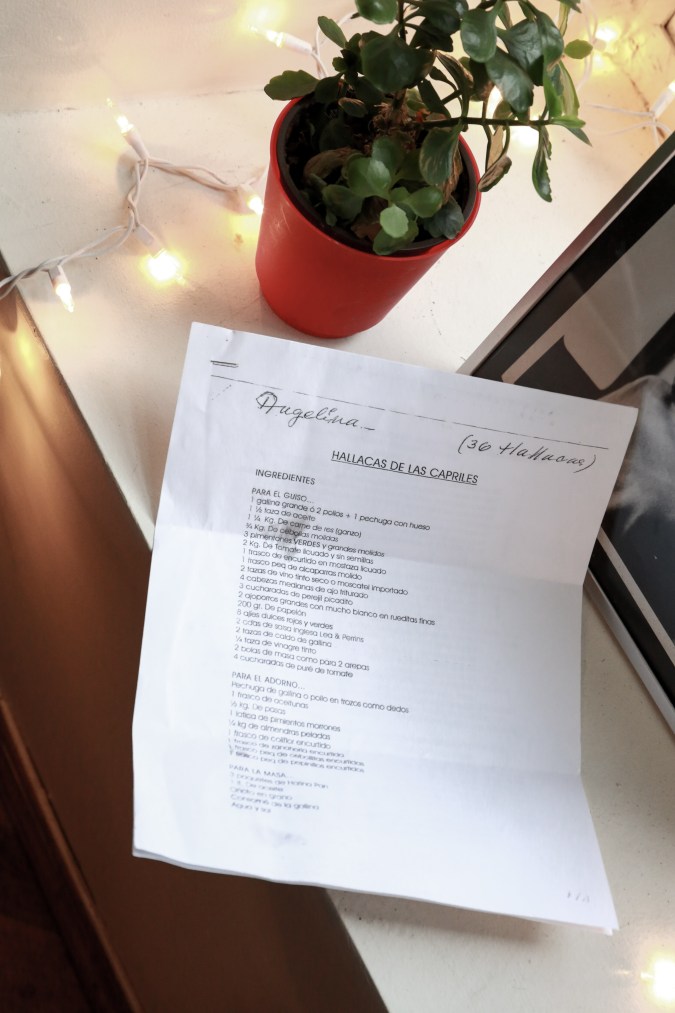

The recipe that Luis and Mariana used to prepare their hallacas came from two sources. The first, as Mariana let me know, has been in her family for ages, a sort of ritual that all of the women in her family have partaken in for generations. Given the amount of labor that goes into making a single hallaca, it is naturally a collaborative affair that really lends itself to a family tradition. There is the actual guiso, which consists of pork and chicken. Then, preparing the masa, along with cleaning the plátano leaves, stuffing the ingredients, wrapping the hallacas, boiling them and so on. It’s a process that takes many steps and can last many hours, depending on how many people are involved.

To color the evening, Mariana played music by her grandfather, Teo Capriles, who performed in various musical ensembles and had a solo career of his own interpreting traditional Venezuelan folk music. Without the proper soundtrack, she told me, it’s not Christmas. At least for a tiny moment, Crown Heights served a surrogate for Caracas. It felt like home.

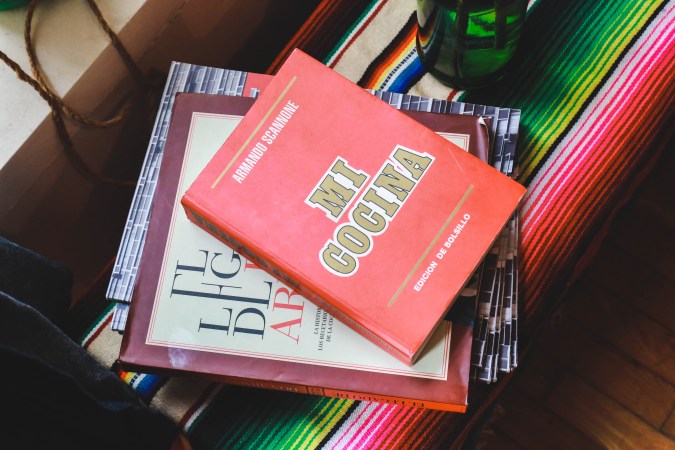

The second source of the hallaca recipe is a little red book titled Mi Cocina, known to many Venezuelans as being the first cookbook to compile all of the country’s traditional recipes in a single place. It was written not by a chef, but a civil engineer named Armando Scannone. It’s a funny coincidence, as Luis himself studied mechanical engineering in college, though he never actually worked in the field. The book has become a bible of sorts for Venezuelan chefs practicing their native cuisine, and Herrera is no exception. He follows the book’s recipe almost to the letter, even going so far as to weigh the amount of masa that is used in each hallaca.

You could say that the synthesis of these two recipes, or traditions, is the perfect combination of science and soul, tradition and technique. Or, you could just say it makes for a damn good hallaca. Maybe I’ll lose some of my credibility as a Mexican-American for admitting this, but I’ve never tasted a tamal that was that good. And even though I’ve never set food in Caracas – and honestly, don’t know that I ever will – something about that evening, and my subsequent Christmas, made me feel as if though I’d lived a little piece of it. For a brief moment, I too felt at home.